Bentham's Blunder (Part 2)

A response to "Moral realism is true"

This is the second post in a series of posts responding to Bentham’s Bulldog’s post, Moral realism is true. This post picks up where Part 1 finished.

5.0 Discovery vs. invention

BB next employs another line of reasoning that does nothing to bolster the case for realism:

This becomes especially clear when we consider moral questions that we’re not sure about. When we try to make a decision about whether abortion is wrong, or eating meat, we’re trying to discover, not invent, the answer.

Again, note that BB simply asserts a realist-friendly reaction to this, rather than presenting anything like an argument. Worse, this is a false dichotomy. The impression BB gives is that when it comes to moral deliberation, we have two options:

Discover the stance-independent moral truth

“Invent” an answer

I reject both of these options. BB gives the impression that if you don’t deliberate with an eye towards stance-independent truth, that you just make up whatever answer you want. This gives the impression that an antirealist is relegated, when it comes to moral deliberation, to a transparently constructive and blatantly arbitrary process of simply deciding in the moment whether they’d like to torture babies or whatever. This is not at all what a moral antirealist is limited to. Consider everyday nonmoral decisions: what career to choose, what clothes to buy, what to have for lunch. Suppose, for a moment, that in these scenarios one’s goal is to optimize with respect to one’s own goals and preferences. That is, suppose we’re not gastronomic realists and fashion realists and so on: when we are trying to decide what clothing to buy, our goal is simply to buy clothing we want to wear and that will optimize for our goals.

Would this mean we instantly know which clothing to buy at the store?

Of course not. What clothing will best serve our interests is not immediate or transparent to us. We may have to think:

I like green more than blue, but I already have more green than blue shirts, so this one’s out

Hmmm, I like the texture of this one, but at that price? Perhaps not

This one is nice, but isn’t this kind of going out of fashion?

This one’s a bit too tight around the arms, but the other one’s too long…

Even when making decisions entirely with respect to our own goals, preferences, and values, and for matters of deliberation where I suspect many readers will agree that, at the very least, we’re not presumptively being realists about the matter at hand, we still have to deliberate and think things through. We don’t simply invent our answers.

When it comes to morality, I don’t invent my values, or invent solutions to moral dilemmas. Yet I still experience moral dilemmas. My moral values are not transparent and obvious to me, nor their application to specific cases is not obvious, nor the degree to which I weigh one moral consideration against another, and so on.

In a certain respect, then, the antirealist can “discover” what is morally right or wrong relative to their own values, preferences, standards, epistemic frameworks, and so on. If BB’s use of “discover” is, by stipulation, limited to discovering the stance-independent moral facts, then BB has presented a genuinely false dichotomy. If, instead, it's flexible enough to be inclusive of conceptions of discovery consistent with antirealism, then an antirealist can choose “discover” just like the realist, then the dichotomy loses all its force and no longer presents a distinction that favors the realist.

BB adds this line:

If the answer were just whatever we or someone else said it was — or if there was no answer — then it would make no sense to deliberate about whether or not it was wrong.

An antirealist is not obliged to characterize moral deliberation in terms of an action being right or wrong entirely on the basis of whether they “say” it is. We can and do employ self-imposed constructive procedures for determining whether specific actions are morally right or wrong. For instance, a moral antirealist can be personally committed to utilitarianism, in that they favor maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering. They may still struggle with the question of whether abortion is moral or immoral because they may not know whether any given abortion policy or stance towards abortion would, if implemented, maximize utility. The idea that if you’re an antirealist that it’d make no sense to deliberate is simply mistaken.

As far as what one would do if “there was no answer,” this again needs to be disambiguated. If there was no answer to whether abortion was morally right or wrong in a realist sense? Or in some other sense? Even if nothing is morally right or wrong in the realist sense, and even if that’s the only sense in which anything is or could be morally right or wrong, such that nothing is morally right or wrong, well, sure, then it wouldn’t make sense to deliberate about whether abortion is “morally right” or “morally wrong.”

So what? What follows from that? Does that mean that the error theorist who holds such a view should just stop thinking about abortion, or not care? No. Absolutely not. Even if you don’t think abortion is, technically speaking, “morally right,” or “morally wrong,” you can still deliberate about what kind of society you want to live in, and what policies would optimize for your preferences, and so on. Nothing about the inability to deliberate specifically about whether something is stance-independently right or wrong has any practical consequences for deliberating about what would optimize for your personal values and preferences. Realists routinely give the impression of something like a “realism or nihilism” gambit: that if you don’t accept a realist framing of deliberation or whatever, that you’re left with nothing. This is complete nonsense.

Imagine if I did the same for taste: You have two options:

Accept that there are stance-independent gastronomic facts governing what you should or shouldn’t eat, according to which when, setting aside all dietary, ethical, financial, and other considerations, and your sole consideration is how good or bad food tastes, you are obligated not to eat foods that taste better to you, but to eat foods that are stance-independently tasty, i.e., tasty independent of how they taste to you or anyone else

Be completely indifferent to taste decisions. You have zero rational basis for preferring to eat foods that taste better to you than ones that taste terrible. It makes absolutely no sense to prefer eating chocolate over feces, or to eat bread instead an equally nutritious and edible pile of nutritive goo that tastes like vomit.

This is, of course, ridiculous. If you reject (1) you’re not obliged to accept (2), or vice versa. I don’t think there are stance-independent facts about what food is tasty or not. This in no way makes it impossible or nonsensical for me to deliberate about what to eat for lunch. It also does not entail that I invent my food preferences.

Likewise, I’m not limited to either discovering stance-independent moral facts or “inventing” moral truths on a whim. BB sets up what is at best a false dichotomy that an antirealist can trivially circumvent.

6.0 Arguing about morality

Next, BB says:

Whenever you argue about morality, it seems you are assuming that there is some right answer — and that answer isn’t made sense by anyone’s attitude towards it.

Again, “it seems.” It seems to who? It doesn’t seem this way to me.

Once again, BB gives the impression that some feature of ordinary thought, like deliberation, or in this case, argumentation, presupposes realism. This is not true.

When people argue about things, they can and do appeal to intersubjective and shared goals and values. Suppose you and I are both committed antirealists and utilitarians. We could, given these commitments, argue about public policy or whether an action was right or wrong relative to our shared moral frameworks. If I argue with a complete stranger, I can and typically do intend to appeal to their own values, or I may wish to prompt them to reconsider their stance or commitments. They may be favoring a policy I dislike and don’t want implemented, so I may seek to get them to recognize this policy isn’t something they’d approve of on reflection. This does not require me to think that they must reflect on what the stance-independent moral facts are. I might just be trying to get them to realize they’re being inconsistent, or a bit of a jerk.

Furthermore, people routinely argue with the intention of achieving their goals, rather than arriving at the truth. Call this “coordination argumentation,” rather than “truth-targeted argumentation,” just to pick the first terms that came to mind. People haggle about the price of goods. This doesn’t entail “price realism.” Friends argue about what pizza toppings to get when ordering pizza. This doesn’t entail “pizza topping realism.” People argue because they want things and other people want things and they need to negotiate.

Absolutely nothing about the fact that people argue lends itself to moral realism. Antirealists can and do argue all the time. We want things, and we frequently assume others do, too. Many arguments are rooted in these simple facts.

In this case, BB seems to think the way people argue implies they think there’s a stance-independently correct answer. But I don’t think BB has shown that this is the case. It instead appears to me that BB is reporting on how things seem to him. I would invite BB to consider that his conception of how things seem may be predicated on simplistic and inaccurate picture of the reasons and motivations people would have for arguing.

Lastly, it’s worth noting just how weak this point would be even if it were true. Suppose when many people argued about moral issues they were supposing some type of moral realism. That might suggest a presumption of moral realism was baked into…what? Much contemporary English? The psychology of Americans? That’s hardly a powerful source of evidence for moral realism.

What BB seems to be trying to show here, which is typical of realist arguments, is that people are generally inclined towards realism, and that perhaps the reader is already inclined towards realism. I don’t think these attempts are successful, but even if they were, they’d establish very little: a very weak presumption in favor of realism. Nothing amounting to a substantive argument in its favor. You can try to build a cumulative case off of a bunch of weak lines of evidence like this, I suppose.

BB goes on to consider some potential rejoinders. They’re not very good, but let’s have a look at the second one (the first is too weak to bother with):

Principle 2: confirmation is needed for a believer to be justified when people disagree with no independent reason to prefer one belief or believer to the other.

BB responds:

Very few people disagree, at least based on initial intuitions, with the judgments I’ve laid out. I did a small poll of people on Twitter, asking the question of whether it would be wrong to torture infants for fun, and would be so even if no one thought it was. So far, 82.6% of people have been in agreement.

This is not a good response. First, BB claims that “Very few people disagree” with the judgments he’s presented. BB makes a vague, underspecified empirical declaration about the psychology of some unknown population of people. What evidence does BB present? A Twitter poll. Twitter polls of the people who see BB’s posts are not representative of any meaningfully relevant population of people. Do these findings generalize to people in general? Who knows, but probably not.

Note that BB has conducted what amounts to an empirical test of people’s metaethical views. There are several limitations with this measure, all of which center on the lack of rigor and care taken to construct a good measure and to assess its validity.

First, we have little information about the representativeness of the sample. That is, whatever proportion BB obtains in conducting this survey, we don’t know how well this proportion represents how people in general would respond. Respondents may be disproportionately likely to agree with BB, or even to disagree.

Furthermore, the results may not be independent; that is, people could potentially see other people’s responses or see comments about those responses prior to responding to the survey.

Third, we have little direct evidence about how participants interpret the question that was asked. This is essential, since unintended interpretations are irrelevant for evaluating a particular hypothesis.

The study is likely also underpowered.

Furthermore, when you present ambiguous, poorly-phrased, and misleading questions, the proportion of people who judge superficially in the direction you find favorable isn’t a good indication that they share your specific position. It’s tricky to craft appropriate questions for probing untrained people’s metaethical judgments. I developed this position because I wrote my dissertation specifically on this topic. BB, along with philosophers in general, underestimate the degree to which ambiguity, pragmatic considerations, normatively loaded remarks, and other factors can contribute to people’s responses to scenarios (especially dichotomous or forced-choice scenarios that restrict one’s answers to a simple, e.g. yes/no) being diagnostic of whether they endorse the position you think they do.

My colleague David Moss and I wrote a short paper addressing this issue which you can find here. The problems we outline here only scratch the surface. It’s incredibly difficult for nonphilosophers to respond to philosophical scenarios in a diagnostic way even when you carefully attempt to disambiguate those questions and avoid biasing factors. BB doesn’t appear to me to put even minimal effort into doing this, and, if anything, seems to me to dial up the ambiguity and biasing aspects of the questions BB poses. As such, I don’t think people’s responses to these questions would be meaningful, anyway.

What we’d really need to know is why people responded in one way or another, and it may turn out in many cases that the reason why had very little to do with a clear and distinctive endorsement of a specific metaethical position, to the exclusion of other, irrelevant considerations (e.g., normative considerations). Realists routinely wrap their framing of realist positions up in a confounding bow, such that normatively desirable implications are entangled with endorsing the realist’s position, while unappealing, repugnant, monstrous, or stupid notions are entangled with the antirealist’s view. You’d need to disambiguate these to show that people favor realist responses for their own sake. Realists presenting scenarios almost never do this, and BB’s scenarios are no exception.

Of course, these findings are only informative if the measures BB used were valid. So even if we set aside the fact that we have almost no reason at all to think BB’s results are representative of people in general, or of any informative population of people at all, there’s still the question of whether BB asked a valid question; that is, a question that consistently and reliably allows us to distinguish people’s views in accord with the stipulated operationalizations; in this case, presumably the goal is to distinguish realists from antirealists. BB simply hasn’t done the work to show that a Twitter poll is sufficient to provide much substantive evidence that his position is widely shared among any meaningful population of people.

Yet one of the most critical deficiencies in appealing to such evidence is that we already have a wealth of more carefully designed empirical studies on how ordinary people respond to questions about metaethics. Such studies have been designed by researchers with the knowledge and training to devise such measures, were gathered under more careful conditions, feature larger sample sizes, feature a wide variety of measures, and employ measures that have been refined for well over a decade to account for and avoid the many methodological pitfalls myself and others have identified with measures of metaethics. Why would BB conduct a flimsy online survey, when there’s already an entire body of empirical literature on the question? Why not appeal to that empirical literature?

Conducting a survey like this is like using a flimsy personal poll as evidence for the proportion of atheists in the United States, while making no mention of Pew or Gallup data. It’s strange. If I conducted a survey of my friends and found most were atheists, I doubt anyone would take this as good evidence that most people are atheists. Does BB not know that there’s already research on metaethics? Does BB not care? Does BB think his own question is better than all the research out there? Thinking you can establish that most people agree with you by conducting a Twitter poll, which will be visible primarily to people who follow you, and will involve a self-selected sample, and for which you’ve shown no indication of having validated or workshopped to iron out ambiguities or confounds in the wording, is bizarre. There’s a whole literature not just on how nonphilosophers think about questions like these, but a literature that I myself am a part of that evaluates the validity of these measures.

Even well-trained psychologists and philosophers who attempt to very carefully solicit people’s metaethical responses using a variety of methods under far more rigorous conditions than BB’s employed struggle to do so. BB’s survey is, to put it bluntly, almost totally uninformative. It’s also weird that BB didn’t include a link to the poll or even what question was asked. I don’t think there’s anything suspicious about that, but it suggests to me an attitude of complacency and lack of awareness for the challenges of constructing a valid question (i.e., a question that actually tells you what you want to know).

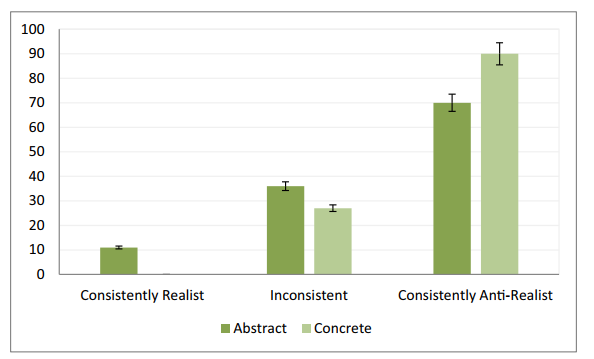

I’ve discussed this so many times it’s become tedious: the best available empirical evidence does not suggest that most people are moral realists, act like moral realists, think like moral realists, speak like moral realists, endorse moral realism, or in any way favor moral realism. The bulk of the psychological research on folk metaethics goes back about twenty years. Over the past two decades, myself and others, such as Thomas Pölzler, Jennifer Wright, James Beebe, Taylor Davis, and David Moss, to name some of the authors involved, have identified methodological shortcomings in earlier research, and have sought to correct for those shortcomings. Newer, and more robust empirical studies tend to find very high rates of antirealism. See, for instance, these results from Pölzler and Wright (2020):

This is Fig. 1, on page 73 of Pölzler and Wright (2020).

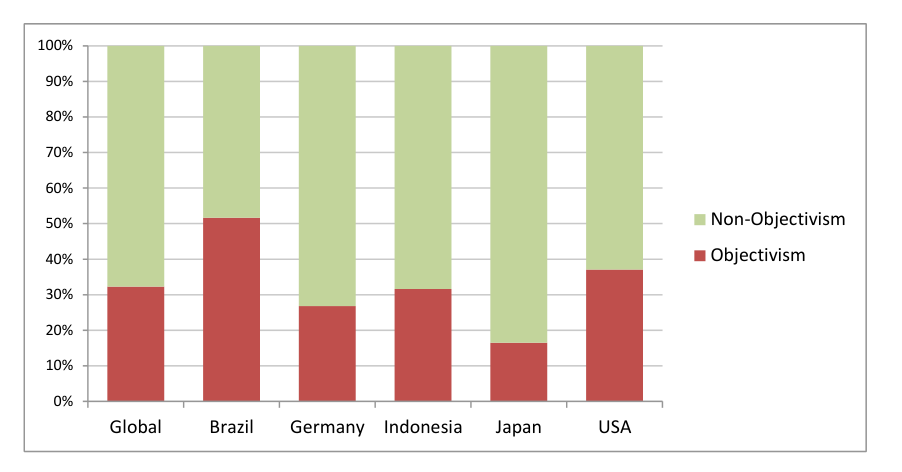

Or consider this more recent, cross-cultural study from Pölzler, Tomabechi, and Suzuki. They employ a range of measures and ways of coding the data, but even if you use their most conservative measure, which amplifies realism to a much greater extent relative to their other methods you still get results like this:

The measures used in these studies may not be valid, or may suffer methodological shortcomings. But they’re more informative than BB’s Twitter poll. At the very least, I’d hope such findings give BB and others pause in the constant and insistent presumption that most people are intuitive moral realists. The data just does not seem to point in this direction at the moment.

BB goes on to say:

Also, those who disagree tend to have views that I think are factually mistaken on independent grounds. Anti-realists seem more likely to adopt other claims that I find implausible.

It seems like BB is providing biographical details. If you share BB’s other views, then maybe this will have some traction. Otherwise, I don’t think it carries much weight if one’s goal is to present a case for moral realism.

Next, BB says:

Additionally, they tend to make the error of not placing significant weight on moral intuitions.

It’s not clear if this is true. Which intuitions? Normative intuitions or metaethical ones? BB’s remark here simply isn’t clear. If BB is talking about metaethical intuitions, most antirealists I know find realism intuitive and put, if anything, more stock into intuitions than I think they should. I’m a bit of an outlier in that I don’t have realist intuitions in the first place. That may put me in good company relative to the general population, since I don’t think they typically have realist intuitions either, but at least among philosophers I think BB’s claim is probably not true. It’s hard to say because it’s too underspecified to readily evaluate.

BB then says:

Thus, I think we have independent reasons to prefer the belief in realism.

We have independent reasons because antirealists tend to hold views BB finds implausible? So is BB just assuming his readers share his intuitions? Maybe they do, but this is starting to look an awful lot like preaching to the choir.

BB next says:

It also seems like a lot of the anti-realists who don’t find the sentence “it’s typically wrong to torture infants for fun and would be so even if everyone disagreed” intuitive, tend to be confused about what moral statements mean — about what it means to say that things are wrong.

Note, again, that BB is talking about how things seem without qualification. Seems to who? Antirealists don’t seem confused to me. If BB thinks we’re confused, it’s BB’s job to present arguments or evidence for that. Simply reporting that “it seems” we’re confused is hardly an argument. I don’t think we are confused. Rather, we simply disagree with you about what those statements mean or what the people making those statements mean. Disagreement is not confusion.

BB then says:

I, on the other hand, like most moral realists, and indeed many anti-realists, understand what the sentence means. Thus, I have direct acquaintance to the coherence of moral sentences — I directly understand what it means to say that things are bad or wrong.

Again, this is a mere assertion. Why should I grant that BB and most moral realists “understand what the sentence means”? BB hasn’t presented any substantive arguments or evidence. What are we to conclude? That BB has demonstrated he understands what a sentence means because he conducted a Twitter poll? BB claims to have direct acquaintance, but what entitles BB to such a claim? Why couldn’t I similarly assert that I, contra BB, am acquainted with the meaning of these terms, and that what they mean better accords with antirealism than realism? Again, BB is not presenting arguments, but just asserting things, and, at best, providing very feeble evidence that is, if anything, overshadowed by evidence to the contrary. Carefully constructed psychological studies are at least better than improvised Twitter polls conducted on one’s personal Twitter account.

BB next says:

If it turned out that a lot of the skeptics of quantum mechanics just turned out to not understand the theory, that would give us good reason to discount their views. This seems to be pretty much the situation in the moral domain.

BB has presented no substantive arguments or evidence that I or any other moral antirealists don’t understand “the moral domain,” or what moral claims mean, or anything of the sort. As far as I can tell, this is simply asserted. There’s also no specification about what proportion of antirealists misunderstood, nor is any supporting evidence of any specific antirealist not understanding anything in particular actually given. Who are these antirealists? What do they not understand? Why does BB think they don’t understand it?

References

Pölzler, T., Tomabechi, T. Suzuki, T. (2023). Lay people deny morality’s objectivivity across cultures (to somewhat different extents and in somewhat different ways). ResearchGate. 10.13140/RG.2.2.24917.19689

Pölzler, T., & Wright, J. C. (2020). Anti-realist pluralism: A new approach to folk metaethics. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 11, 53-82.

I remember when Matthew did that Twitter poll - I voted on it. I voted that torture would still be wrong even if everyone approved it. I interpreted the question as one about my normative views, not my meta-ethical ones.

Later at some point I had an exchange with Matthew about this talking point. I told him that the claim that X would still be wrong even if everyone approved of it is compatible with anti-realism.

I gave the following example to illustrate my point:

Suppose that every utilitarian either dies or converts to deontology. It is still the case that pushing the fat man is right relative to the standards of utilitarianism, even if no one actually abides by those standards.

Matthew bizarrely responded to this by telling me that things couldn’t be stance-dependently right or wrong if the stance was just hypothetical.

Meanwhile if we take a look at the IEP, they say this:

“Constructivism ought to be understood by contrast as a species of a stance-dependent view. On this account, there are no moral, or ethical, truths that obtain entirely independently of any actual or hypothetical perspective. The standards that fix the relevant class of ethical facts are always made true by virtue of their ratification from within some actual or hypothetical perspective.”

They explicitly make reference to hypothetical perspectives when describing how moral truths can be stance-dependent.

How many of the respondents to the Twitter poll did interpret the question as ”If you thought torturing babies for fun wasn’t wrong, would you still consider it wrong?” rather than, for example, ”If everyone else thought torturing babies for fun wasn’t wrong, would you still consider it wrong?”. The poll result doesn’t give you that information. The first sentence looks like a contradiction. But, I would argue, it is a valid reformulation of the poll question. Therefore, we have ”independent reasons” to reject moral realism, since moral realists seem to hold impossible views. Check mate, realists!