Henry Shevlin's popular relativism post: A response

1.0 Introduction

The philosopher Henry Shevlin recently made a remark about moral relativism. For whatever reason, Henry’s tweet became very popular. It’s now been viewed more than 1.8 million times, has been retweeted 5,000+ times, has 50,000 likes, and there are 688 responses. This is the most popular metaethics post I’ve ever seen. Given that I think it perpetuates misunderstandings about metaethics, I think that’s very unfortunate, and I hope I can correct the record. Here is the remark:

What’s bizarre about this? As far as I can tell: nothing. Being a relativist or thinking that morality is culturally constructed is consistent with having unshakable ethical convictions and with viewing disagreeing as “moral monstrosity.” This is especially the case if you’re an appraiser relativist.

Agent relativists may struggle a bit with the monstrosity part: it’s a bit odd to think that whether an action is right or wrong depends on the standards of the person performing the action (or their culture), but to then be outraged by people acting on those standards: after all, they’re acting in a morally acceptable way! So why be outraged by their disagreements?

But Henry does not specify that the students in question are agent relativists in particular. Are they? If so, why not specify this? And how does he know what kind of relativist they are? Did they clarify? Why use the term “relativism” without adequate disambiguation? Even if they are, there’s no inconsistency with being an agent relativist and having “unshakeable ethical convictions,” so there’d still be a problem with this remark.

At best, then, there may be some tension between some forms of relativism and one of the two components of (2). So even if there is an issue here, it’s buried under a lack of clarity and is at best only partially legitimate…assuming I’ve interpreted these remarks correctly, but it’s possible I haven’t. I understand that it’s Twitter and you can’t provide infinite amounts of detail, but you can post additional remarks to clarify an initial remark. I didn’t see that here.

More generally, there appears to be a common sentiment that if you’re a relativist, that you have less reason to be committed to your values. Is this what Henry means? I am not sure; the remark simply isn’t clear enough. Perhaps Henry will clarify. I reviewed the tweet and some responses to it last night on my YouTube channel, where I went into more detail about what my issues with the remark and the responses to it were. Check that out here.

Let’s have a look at some of the replies. Maybe that will help clarify matters, and will give us some insight into what others think and how they interpreted the tweet.

2.0 Conflicting intuitions

The Experimental Philosophy twitter account states the following:

Research in experimental philosophy often shows more variation in people’s intuitions than philosophers have otherwise supposed. The point here is that this doesn’t always manifest as some people having intuition A, and others having intuition not-A, but that individuals often have intuitions in favor of both A and not-A. This is an interesting finding and it wouldn’t surprise me if this did turn out to be true.

An unfortunate feature of many studies is that they employ forced choice paradigms. This means participants are required to choose from among a limited and discrete set of options. For instance, you may be asked a question like this:

Do all slithy toves gyre and gimble in the wabe?

□ Yes

□ No

Questions like these are unable to detect ambivalence or conflicting intuitions because they require participants to express only one of potentially multiple conflicting intuitions. It takes extra work to recognize that people may have conflicting positions on a given issue. It’s remarkable that active efforts to detect ambivalence or conflicting intuitions weren’t pursued sooner, but it’s great that they are now.

That people may have conflicting intuitions is one more reason to worry about contemporary analytic philosophy’s methods. People who begin studying philosophy may start out with mixed intuitions, but as they are taught to hold consistent views, strive to prune inconsistencies in ways that are not epistemologically legitimate: a commitment to consistency may prompt people to set aside intuitions for reasons other than their non-diagnosticity of the truth.

3.0 Only a feeling

Next, we have this remark:

This may very well be true. I don’t have much in the way of an objection or commentary on this. Sure, some people can offer reasons and some can’t. No problem. And this particular tweet may be drawing attention to a growing trend among students of being intolerant of opposing points of view and unwilling to engage with people who hold contrary moral (or political) positions. If so, that’s worth discussing, but it’s not at all clear how closely it relates to relativism and, even if it is related, there’s a big difference between the convoluted and underdeveloped views of untrained people and the defensibility of a philosophical view itself. That students without training hold muddled relativistic views isn’t a good reason to think relativism is false. This tweet doesn’t suggest otherwise; I’m pointing to a more general issue with criticisms of relativism: they often focus on what students say or think, not drawing a distinction between the views of random untrained people and the views themselves. Chances are if I went out and spoke to random Christians they’d have muddled and confused theological views. That would not, by itself, be a good reason to think Christianity is false.

In any case, what concerns me is this response to the previous tweet:

I am more inclined to think the disdain this person shows towards their students is a bit monstrous.

4.0 Cognitive Dissonance

Next, we have this remark:

Henry’s response appears to confirm that he thinks there is some kind of cognitive dissonance between (1) and (2) in the original tweet. Cognitive dissonance arises when one has two or more views that are in tension with one another; it remains unclear to me what the tension is supposed to be, since it isn’t clearly spelled out.

Henry’s response supports my concerns that his original tweet isn’t secretly totally reasonable. Look at what he says here:

It's weird that students can hear JL Mackie's error theory ("there are no ethical truths") and are totally unphased, yet when asked to consider e.g. Nozickian libertarianism find it absolutely morally abhorrent.

There is absolutely nothing weird about this. Error theory has no practical implications at all. Error theory holds that ordinary moral claims involve an implicit commitment to stance-independent moral facts. There are no such moral facts, so all such claims are false. This has a superficially alarming consequence. Statements like this:

It’s morally wrong to torture babies for fun.

…are false. The shock! The horror! Only, once you analyze what this means, it amounts to this:

It’s stance-independently wrong to torture babies for fun

…is false. Well, suppose it’s not true that it’s stance-independently wrong to torture babies just for fun. So what? This has no practical implications at all. This tells us nothing about the preferences, attitudes, values, or disposition of the person who arrives at this conclusion. They can be just as anti-baby torture as anyone else. So if students are unfazed by Mackie’s remarks: good. They shouldn’t be fazed. The implementation of Nozick’s libertarianism, on the other hand, has clear and rather titanic practical implications, so it makes sense for students to have a position on the matter and, if they think libertarianism would be catastrophic, to regard it as abhorrent.

Not only do I not find anything weird in what Henry describes, the reactions he describes strike me as completely sensible and, if anything, an impressively consistent reaction from students. If anything, what I find weird is Henry finding this weird. Note, too, that he doesn’t spell out why it’s weird. Why not spell it out?

We have more from Phillipe. Look at this exchange:

Good job, Kaiden. Philippe-Antoine’s response, though, oof. Let’s break this down:

This sounds to me like getting very upset that other people don't go see the movies you like or prefer a different drink than you do.

This is silly. As I point out in my video reviewing Henry’s initial remarks, there are at least three differences between one’s stance towards moral issues and one’s taste standards:

Their metanormative status. This concerns whether one is a normative realist or antirealist about the domain in question (e.g., morality, taste, etc.)

Their scope. This concerns who the standards apply to. One may endorse a standard that applies only to one’s personal conduct, or one may endorse a standard that applies to members of various groups (e.g., all members of your culture, all rational agents, etc.)

Their personal importance. This is fairly self-explanatory. This concerns the degree to which you regard the matter as important. You could regard one belief or value as extremely important (say, a 100/100) and another fairly unimportant (10/100).

I say that critics of antirealist views are silly because they fail to disambiguate these considerations, all of which are completely orthogonal to one another, and mistakenly think that if you hold that you’re an antirealist about your moral standards in the same way you are about your taste preferences (that is, your stance with respect to their metanormative status is identical) that you regard them as similar with respect to scope and/or personal importance. Yet this is false. You can hold this view:

Morality

Stance-dependent

Universal in scope (my moral standards apply to everyone)

Extremely high importance

Taste

Stance-dependent

Local in scope (my taste preferences only apply to me)

Variable but mostly low to moderate importance

Philippe has committed what I will provisionally dub the overcomparison fallacy. The overcomparison fallacy occurs whenever a person mistakenly infers that if you compare two things with respect to a shared property, that you are thereby comparing them along other dimensions as well, even if you aren’t doing so and even if those similarity with respect to those other dimensions is not logically entailed or implied by your comparison. For instance, suppose I state that the sun and a lemon are both similar in that they are yellow, signified by {Y} (please don’t comment to say something like the “sun isn’t really yellow; it only appears that way from earth due to the way our atmosphere influences light waves from the sun). So I am saying that:

Sun: {Y}

Lemon: {Y}

Well, the sun and lemons have other properties. The sun is hot {H}, large {L}, and bright {B}. Lemons are sour {S}, tiny {T}, and high in vitamin C {C}. So if we list off their properties we get:

Sun: {Y, H, L, B}

Lemon: {Y, S, T, C}

When I compare the two with respect to their color, I am only comparing them with respect to {Y}, not with respect to their other properties. Yet sometimes, when you compare two things and specify a point of comparison, people will mistakenly take you to be comparing them in other respects.

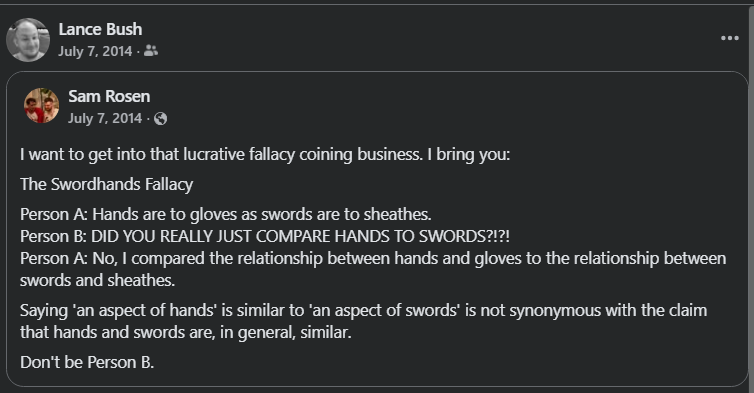

[Edited to add on 12/13/2025]: A friend of mine, Sam Rosen, let me know that he had proposed the idea of the overcomparison fallacy some years ago, but provided a different name:

I want to get into that lucrative fallacy coining business. I bring you:

The Swordhands Fallacy

Person A: Hands are to gloves as swords are to sheathes.

Person B: DID YOU REALLY JUST COMPARE HANDS TO SWORDS?!?!

Person A: No, I compared the relationship between hands and gloves to the relationship between swords and sheathes.

Saying ‘an aspect of hands’ is similar to ‘an aspect of swords’ is not synonymous with the claim that hands and swords are, in general, similar.

Don’t be Person B.

Sam called this same mistake the Swordhands Fallacy. So if you prefer that name, go ahead and use it, and we’ll see which term has greater memetics legs.

Either way, I’m happy to cede the origin of the fallacy to Sam. There is a very good chance that I got the idea to recognize this as a distinct fallacy directly from Sam and the notion rolled around in my mind for a decade or so until I decided to write about it here. Regardless, Sam deserves whatever credit there is for distinguishing this mistake first (unless someone preceded both of us). More generally, Sam is an incredibly creative thinker who is especially good at insightfully novel notions. [End Edit]

Philippe-Antoine is doing that in this response. When a relativist gets upset at other people this should not sound like

[…] getting very upset that other people don't go see the movies you like or prefer a different drink than you do.

This interpretation seems to imply that because it would be objectionable to get upset at others for having different taste preferences, that it would likewise be objectionable to be upset with others for having different moral standards. But this would only be true if the moral relativist also regarded morality as having limited scope and/or less importance, neither of which is an entailment of being a relativist. Relativism only applies to the metanormative status of your moral standards.

Philippe-Antoine’s other remarks don’t help, either. He also says:

Well, no. Let's not exaggerate. Everything depends on what you mean by 'I have enormous conviction in my sense of morality.' If you mean 'I find myself in the thrall of uncontrollable emotions when I see certain things,' then okay, no need for cognitive dissonance.

This is a highly uncharitable and inappropriate way to frame antirealist opposition. The implication here is that you can avoid cognitive dissonance if, in stating that you have strong moral convictions, that you are

“in the thrall of uncontrollable emotions”

This is complete nonsense, and a deplorable thing to say. Being a moral antirealist doesn’t require you to be in the “thrall” of “uncontrollable” emotions to avoid the alleged “dissonance” of being a relativist/antirealist and having strong moral convictions. There simply is no inconsistency or dissonance caused by not thinking your moral standards are stance-independently true but nevertheless being deeply committed to them. This doesn’t require a lack of emotional control. I have strong moral convictions, I am an antirealist, and I am no less in control of my feelings than anyone else.

Philippe-Antoine goes on to say:

We're all prone to emotions and other feelings--nausea, whatever--that just happen. But if, upon stepping back, you think that these feelings are neither correct or incorrect, such that they're no more and no less arbitrary than aesthetic judgments or other preferences...

Then yes, I understand how these two beliefs hang together.

First of all, being an realist or antirealist does not require that your moral standards are just emotions, much less uncontrollable ones. You can have convictions, values, beliefs, attitudes, preferences, and so on without these being reducible to something as specific as an emotion. So Philippe-Antoine’s construal of the psychological states available to antirealists is presumptuous, dubious, unsupported, and very likely wrong.

Second, what exactly does it mean to say that my moral standards are “arbitrary”? If by this one means that there is no principled rationale rooted in some set of stance-independent principles or justifications for holding one view over another, well, I’ll happily acknowledge that my preferences are arbitrary. So what? How does that in any way inconsistent with having a strong conviction on the matter? Maybe if Philippe-Antoine can’t understand how the two beliefs hang together, that’s a problem for him to work out. But if he can’t spell out what the problem is, I don’t see why I or any other antirealist should be inclined to take him seriously.

Philippe-Antoine persists in making these same mistakes, even after pushback:

Philippe-Antoine continues to push the comparison to aesthetics above. When he says:

[…] then this is like having a strong conviction about how art should be done. If there's no fact of the matter, why have the conviction?

Like it in what respect? If you’re an antirealist about both, the only point of similarity is with respect to neither involving stance-independent normative facts. This does not entail that they’re alike in terms of scope or personal importance. Why doesn’t Philippe-Antoine clarify how they’re allegedly similar? Why not disambiguate and specify? Isn’t that one of the central tasks of analytic philosophers? Why, when people are dealing with relativism, do they suddenly lose all ability to be clear, precise, and specific, and reach for bottom tier objections like this?

But the last remark is even more outrageous:

Sounds like you're saying "nothing is right, but I'm passionately convinced some things are right...no?"

The term “convinced” would be more appropriate a term for a realist. I prefer vanilla over chocolate ice cream, but it sounds a little infelicitous to say that I am “convinced” of this. Such language is more appropriate for belief in stance-independent truths. So he’s already distorting the language antirealists are likely to use in ways that can more readily give the impression that antirealists are saying stupid and contradictory things. That’s not good.

Second, moral antirealists think that nothing is stance-independently morally right or wrong. This does not mean we don’t think things are right or wrong in ways consistent with antirealism. Yet here he is depicting antirealists as having blatantly self-contradictory beliefs. Having a strong moral conviction that something is morally wrong does not entail or require that you must think it’s stance-independently wrong. There is no contradiction here:

I have a strong personal moral conviction that it’s morally wrong to torture babies for fun.

It is not stance-independently wrong to torture babies for fun.

There simply is no contradiction. Yet Philippe-Antoine seems to be unable to distinguish between these claims.

Do I really have to explain that someone can think something is “good” in a sense consistent with antirealism but not good in a sense inconsistent with antirealism? Compare this to a comment a person could make about movies:

I find Van Gogh’s The Starry Night absolutely incredible and mesmerizing. It is one of my favorite paintings. It’s just really really good and I am convinced it is one of the best paintings ever.

Suppose this person also says:

Beauty is an entirely subjective matter. Whether a piece of art is good or bad is entirely a matter of individual preference.

It would be incredibly foolish to say that this person thinks that:

No art is good, but I am passionately convinced Van Gogh’s art is good.

Aesthetic antirealism doesn’t commit you to thinking that “no art is good.” Even if you were an aesthetic error theorist, and you wanted to avoid saying that art is “good,” you could still say things like “I find this art to be beautiful” or “This is my favorite piece of art,” both of which are entirely consistent with saying that no art is [stance-independently] good.

5.0 Conceding too much

Next, we have this remark:

This concedes too much, and this is a common and unfortunate pattern for defenders of moral antirealism. It isn’t simply that strong convictions aren’t necessarily precluded by moral relativism, they are not precluded at all. At the same time, nothing about belief in moral realism entails that one has strong moral convictions, especially if you’re a motivational externalist: on such a view, it’d be consistent with being a moral realist to be completely indifferent to one’s moral standards.

Meanwhile, it’d make far less sense to have little or no conviction in your moral values if you’re an emotivist or stance-dependent cognitivist: after all, your moral values just are your emotions or stances; it’s implausible you wouldn’t have any commitment to those! Thus, ironically, some forms of moral antirealism actually can more readily make sense of moral conviction than common forms of moral realism, which often explicitly exclude any requirement that one have any moral convictions at all.

I also disagree with Krishangh that

It takes some effort to justify but one can passionately defend ones ideals while understanding they are almost entirely arbitrary and the result of cultural influence and evolution

On the contrary, it takes no effort at all: I outright deny that my moral values require any “justification,” and they are trivially easy to “defend”: I simply act on them, and if other people don’t like it, too bad. I don’t feel any obligation to provide a “justification” for opposing genocide or baby torture or whatever. I oppose them. It’s as simple as that.

What’s unsettling is that Henry’s response to this implies that he endorses Philippe-Antoine’s poor comparison above, which committed the overcomparison fallacy:

This is silly. No, an antirealist/relativist disagreeing about moral issues is not doing something objectionable like saying “I prefer Mozart and you prefer Beethoven, you monster.” Personal music preferences have little or no practical implications for others. So if someone else listens to Beethoven in the privacy of their home, this has no implications for me. But their moral conduct does: if they go around stabbing, robbing, and killing other people, they threaten me and the society they live in. Even if they didn’t, there’s no contradiction and no necessary similarity in opposing what other people do on moral grounds but not aesthetic grounds since, as I noted before, moral values can differ in scope and importance.

Henry draws attention to a music preference. But music preferences aren’t typically regarded as all that important, nor would any of us find it acceptable for people to go around forcing our music preferences on others. Is this “like” going around forcing people to abstain from murder or genocide? Well, in what respect? It’d certainly be similar in that you are imposing your standards on others, but if that’s the point of comparison, well, I fail to see what the issue is. I am entirely fine saying that I am in favor of:

Imposing my opposition to genocide on everyone

Not imposing my music preferences on anyone

Henry’s remark conflates the normative/practical implications of imposing the latter on others with the former, as if the moral antirealist, in imposing their moral standards on others, must regard their standards as just as practically irrelevant and unimportant as one’s music preferences. This is a tendentious and misleading way to frame the similarities and differences between morality and taste preferences. It’s incredible that so few people have pointed this out and objected to it.

Henry repeats this sentiment elsewhere:

What does it mean to put them on the same “footing”? This is terribly unclear. It means you treat both as not being stance-independent. They’re similar in that respect. But again, so what?

I like strawberries, you like raspberries. While I might hate you for your preference, I can't claim any high ground to justify it unless I think there are objective facts to back that up.

An antirealist doesn’t need to “claim any high ground” to “justify” the imposition of their moral values on others. Even if this required there to be objective facts, so what? This is at best, either false and presumptuous, or trivial.

False: An antirealist may argue that there are conceptions of claiming the high ground and justifying their moral standards that don’t require an appeal to stance-independent moral facts, in which case, this statement is false.

True: Great, then an antirealist can just concede that in the respect specified, they can’t “claim the high ground” to “justify” imposing their standards on others. So what? I never agreed that I need to be able to do this, take myself to be doing this, or care at all about doing so. Antirealists don’t have to jump through an obstacle course created by moral realists to have a defensible position that isn’t full of contradictions. We can just walk away from the obstacle course. I have zero interest in “claiming the high ground” or “justifying” my opposition to, e.g., genocide.

Think about it this way. Suppose moral realism is false. If it is, then, as per Henry’s remarks, none of us could “claim the high ground” to “justify” our opposition to genocide. Now let’s suppose someone says they’re off to go commit genocide for the day, unless you stop them. What would you do? Keep in mind genocide in this hypothetical is not stance-independently wrong. Would you just shrug and let them go commit genocide? I wouldn’t. I’d try to stop them. And I wouldn’t care in the least that I couldn’t “claim the high ground” or “justify” doing so. I don’t care about that. I care about the world having less genocide.

What about you, moral realists? Are you so committed to moral realism that you don’t personally care about opposing genocide unless it’s stance-independently wrong? If so, then I’m not sure you should be the ones claiming a monopoly on the high ground on moral issues.

6.0 Convictions don’t make you a realist

We have a comment indicating they interpreted the original post as drawing attention to an alleged contradiction:

Recall the original remark:

(1) They insist morality is entirely relative and culturally constructed... (2) ...while simultaneously holding unshakeable ethical convictions and viewing disagreement as moral monstrosity.

…What’s the contradiction here? Nothing in (2) indicates that the person thinks morality is “absolute.” Then we have bizarre remarks like:

They wanted to respect different perspectives, but when faced with real ethical failures—sweatshops, bribery, environmental destruction—they felt outrage, not moral relativism.

Moral relativism isn’t something you feel. This isn’t an apt comparison. Feeling outrage is completely consistent with relativism, but the pragmatic implication here is that if you feel outrage about what goes on in other parts of the world, that this is somehow inconsistent with relativism. It isn’t.

By the end, they weren’t choosing sides between relativism and conviction—they were learning how to think, how to engage disagreement with depth, and how to act with both principle and humility. And in the real world, that’s what ethics is about.

There are no sides to choose here. Both are completely consistent with one another.

I’m not the only person to notice issues with remarks like these. Consider this response:

…Yep.

7.0 No it doesn’t

Next, we have this:

I will provide a comprehensive analysis of these remarks:

“Everything is relative” means “I can’t be wrong.”

No it doesn’t.

“Disagreement is monstrous” means “You’re wrong.”

No it doesn’t.

Both are tactics, not principles, applied as needed to achieve goals.

No they aren’t.

I wouldn’t put it this colorfully, but this is the first response to this tweet:

I wouldn’t put this quite this way, but I chose this tweet to highlight the presumptuousness of respondents and the poor quality of their analysis of what people mean and how they think. I was advised to be charitable in interpreting Henry’s remarks, which is surprising, given how incredibly uncharitable people are towards the students in undergraduate classes.

There are similar remarks, like this one, as well:

Saying that there is no absolute truth does not require you to think that the claim that there is no absolute truth is an absolute truth. “There is no absolute truth” is consistent both with meaning this in an absolute sense and not meaning it in an absolute sense. For whatever reason, people who think there are absolute truths will mistakenly infer that if someone says there aren’t, that this is a claim of absolute truth. But it doesn’t have to be, and this isn’t a charitable way of interpreting what someone says.

8.0 Not the only critic

I am not the only critic. Consider this tweet. It is too long to post in its entirety here, so I’ll snip out some excerpts:

Henry, this post really surprises me.

I presume that your training is in metaethics in the school of Anglo-American analytic philosophy? If so, I don’t understand how this issue arises.

I would have been surprised by remarks like these coming from philosophers if I didn’t see them so often, but I am glad someone is drawing attention to the fact that the sources of analytic philosophy should make it fairly easy to see why (1) and (2) are not necessarily contradictory or even in any tension with one another. Paul goes on:

The lack of belief in moral realism (there are a whole bunch of variations that can encompass, some of which admittedly may have bearing on what we’re talking about) is an ontological claim.

That doesn’t have to impact the depth of moral convictions nor the view that an assertion of moral disagreement is abhorrent. There are views in which that can turn out to be the case, but far from every view.

9.0 A few final tweets

Moral Relativism is the root problem with the world today. Relativism, in general, is the root.

Why is relativism the root problem with the world today? What’s the problem, exactly, and how is relativism contributing to it? This seems like an empirical question, and I don’t know of any evidence that would support it.

Good luck! I taught ethics to MBAs for many years. It was difficult, but many got the message and understood it. Now, I'm not so sure that would be the case. Sad...

What exactly is the message?

Maybe should start w logic first

Maybe you should. There is no contradiction in the original tweet.

An ideology of contradictions has a very short window of relevance. It is quickly unraveling

What’s the contradiction?

Homo sapiens were always bad at logic... I've observed for 50 years

Yes, and perhaps you’re one of the ones who’s bad at it, since there is no contradiction in the original set of claims.

So they fail basic logic

No, but you do.

Only if they’re agent cultural relativists, and not some other type of relativist. Do we have any compelling evidence that students specifically endorse agent cultural relativism?

Yet another remark suggesting some kind of problem with the logic of a moral relativist having moral convictions:

Why? There’s no contradiction in the original remark.

We have someone associating relativism with postmodernism:

Moral antirealism/relativism don’t require or entail postmodernism. I’m not a postmodernist and I’m not a fan of it. Being a moral antirealist/relativist does not indicate that one doesn’t have coherent beliefs. The beliefs in the original tweet aren’t necessarily incoherent.

We have this:

When a relativist holds that dictators are doing something wrong when they murder millions, they are judging them to be wrong relative to their standards. There can be any number of reasons why they make such a judgment. “It’s all relative” does not entail that there “should be no judgment.” The only farce is the consistent inability for critics of relativism/antirealism to distinguish appraiser and agent relativism, treat relativism only as the latter, and then try to dunk on over “relativism” while not drawing a very basic distinction.

10.0 Conclusion

I could keep going. There are hundreds of posts like these. But I have to stop somewhere. I want to strike while the iron is hot and, hopefully, this post will receive some uptake over on Twitter and get some engagement. Fortunately, some people have started to notice that I weigh in on these things regularly:

I’m here!

I hope in canvassing this many remarks about relativism/antirealism, I have illustrated the dismal quality of public discourse on metaethics. At least some of the people involved in these discussions are philosophers, and they, too, make many of what strike me as very basic errors. I find this alarming and frustrating. And who knows, maybe I’m totally out to lunch and they’re all making fantastic points. I doubt it, but to those who I’ve critiqued in the thread: you’re welcome to reach out to post a response on my blog either as a comment or a critical blog response I’d be happy to host. You can also join me as a guest on my YouTube channel or reach out by email.

Lance, thanks a lot for writing this. I'm a moral realist myself, and don't always see eye to eye with you on metaethics - but as I read through this post, I found myself nodding my head a lot in agreement.

In particular, I think your account of how people go from being laypeople with mixed intuitions to being trained to prune them because they're philosophically inconsistent is quite right (although I think the process itself is/can be epistemically legitimate). And I haven't seen many other people talking about this, and sometimes even seen people talk as if it wasn't true (eg. when they poll laypeople about their ethical intuitions and then are surprised that those intuitions conflict).

I think the most charitable reading of Shevlin and Hoyeck is that they think it's in some way *arrogant* to be a relativist who insists that others follow their moral standards. For instance, if someone thought that morality was stance-dependent because it can be reduced to eg. cultural standards, then to insist that everyone else follow your ethical convictions (and refuse to brook disagreement) might seem a little brash because it seems to imply that your culture is better than everyone else's. This, I think, is why Hoyeck makes the remark about taste in movies - he's internally comparing the arrogance of thinking your culture is better than everyone else's to the arrogance of thinking your taste in movies is better than everyone else's. (Although I don't even know if that analogy is good at face value; how many serious movie connoisseurs will have an unshakeable conviction that I'm wrong if I insist that Boss Baby is the best movie ever made?)

Anyway, I think that's the least objectionable construction of their tweets. But even that formulation still leaves much to be criticized. What's bizarre about undergraduates being a bit brash in their ethical beliefs? Heck, even if they *are* philosophically inconsistent, what's bizarre about that? They're going to your class *in order* to learn philosophical skills like maintaining a consistent position, reflecting on your ethical intuitions, learning to rigorously formulate your arguments so you don't assert more than you can prove, and so forth. Of course undergraduates aren't intellectually perfect; it's your job, as an ethics professor, to teach them how to better themselves, rather than publicly making fun of them for not being already perfect. I wouldn't want to be one of Shevlin or Hoyeck's students, if that's the disposition they have towards undergrads.

Also, the "in 2025" references are just weird. University freshmen thinking that all morality is relative and "just your opinion, man" is a phenomenon that's been around for a very long time. r/askphilosophy, an online forum for laypeople to ask questions to philosophers, has an FAQ section on it because it's such a common question. Moral relativity is an incredibly common ethical intuition amongst laypeople! It's straight up conspiratorial thinking to lay that at the feet of a "cult of feeling" caused by therapy and over-affirmation. And of course, serious moral relativists have much more to say about morality than "it's just a feeling", and it's intellectually dishonest to lump them in with the unprepared remarks of philosophical undergrads.

So, from the POV of a moral realist: these guys are being really unserious. I disavow them, I was annoyed to read their tweets, and I want to reassure you that we aren't all like this. There are way better arguments for moral realism than picking on first year undergraduates for having ethical stances that, everything considered, aren't even that odd or far-out.

PS: Some of the responders seem motivated by culture war stuff (eg. the random references to "postmodern philosophy", therapy, "overly affirmed" kids, "moral relativism is the root problem with the world today", etc.) more than genuine philosophical disagreement. Normally I wouldn't bring this up, but if they're going to talk about "cults of feeling"...

Thanks for the post. It was an interesting read. I did, however, think that perhaps you were slightly missing the point of Henry’s tweet (full disclosure I am an old friend of his). My immediate thought was that his point was more pedagogical than metaethical. I also teach philosophy, though at secondary school rather than university, and his tweet chimed with me. What I find interesting (perhaps even ‘bizarre’) is the way that many students are ready and willing to engage in pretty subtle reasoning at the metaethical level, following the line via Moore, Ayer, Hare, Gibbard, Mackie etc… to arrive at a considered anti-realism; but those same students on normative questions seem to be not only absolutely certain of their views but often unwilling to debate them and can even be hostile to intellectual challenges. While I appreciate anecdotes are not data, this certainly has been a pretty common experience for me over the last 15 years of teaching moral philosophy to adolescents. Perhaps the issue being highlighted by Henry isn’t revealing some analytic contradiction, but a tension in how students reason in the different domains of metaethics and normative ethics?

Wading into metaethical waters (a risky endeavour, I am hardly a strong swimmer), I would say that, as a moral realist, I do struggle to comprehend how anti-realists justify specific normative claims. This is particularly so on what you highlight as the question of scope. I certainly don’t doubt that the conative aspect of a moral judgement allows for a subject to hold views that are stance-dependent and to varying degrees of importance. Where I struggle is in justification of the universal scope (or prescriptive element) characteristic of moral claims. I (and I think most non-philosophers) have an intuition that there is an important difference between me saying “I strongly desire that you abstain from acting in this way” and “for you to act in this way is morally wrong”. I also have a strong intuition (again I think shared by most non-philosophers) that a claim for some normative prescription of universal scope should be justifiable. As the moral anti-realist lacks any stance independent element they have nothing but the conative element (whether personal, or culturally augmented) underpinning their expression of a claim’s universal scope. However this conative element lacks the ability to justify the universal scope being asserted, as the desire of a subject (no matter how strongly felt) cannot bridge the gap between ‘I strongly desire all do x’ and ‘x is morally mandated’. While I agree with you that there is no analytic contradiction here, and no necessary cognitive dissonance, I do think this is a problem. Perhaps the best way to describe it would be, following Philippa Foot’s terminology, a mistake of practical reasoning. To justify a universal scope prescription is not a task that can be performed without some recourse to something stance-independent; on the other hand to claim that we do not need to justify a claim of universal scope is to fall short of the normativity moral claims require.