If you're a relativist, why should I care if you think something is wrong?

Twitter Tuesday #51

People sometimes object to moral antirealists by posing a question like this:

If your morals are just your preferences, why should anyone care about your moral position?

Or they may present a hypothetical:

Suppose I wanted to punch you in the face and take your lunch money. You say this is “wrong,” but all this means is that you disapprove of these actions. Why should I care?

These questions often operate as an implied critique of antirealism. The intent is to show that the antirealist’s characterization of morality is flawed in some way. The question could be taken to reveal that the antirealist lacks the ability to “ground” or “justify” their moral standards, or it may be used to suggest that, since the antirealist does think people “should” comply with their moral standards, that their everyday attitudes and practices of holding others accountable and believing they should comport with the antirealist’s moral values reveals an implicit commitment to moral realism.

This question can prove effective from a rhetorical perspective. Antirealists may flounder in response, unable to offer a compelling reply. What I want to do here is present an example of this occurring in the real world, argue that the question is defective, and describe how I think antirealists ought to respond.

Here is our sample instance of this critique taking place in the wild. It begins with someone observing that:

This discussion begins with someone providing two quotes from the same person. The first is a response to a theistic argument for moral realism by characterizing the view as “The only thing stopping me from murder is the bible”, calling this a “crazy thing to admit about yourself.” The second is an expression of happiness that a national abortion ban failed, implying at least some degree of alignment with a prochoice stance on abortion:

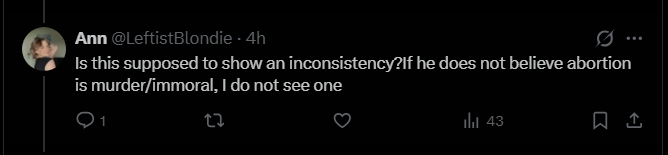

Ann, a guest on my YouTube channel, asked whether this was intended to “show an inconsistency”:

Another person then entered this discussion, asking:

Surely, SURELY YOU SEE HOW THIS UNDERMINES YOUR ENTIRE POSITION??!!???

To which Ann responds:

Nope. A non theist can find abortion immoral or morally justified. If murder is considered unjustified killing and he believes abortion is justified, then there’s no issue because abortion isn’t murder. Instead of sperging in all caps, please explain.

Here is where we get to the occurrence of “Why should others care?” question:

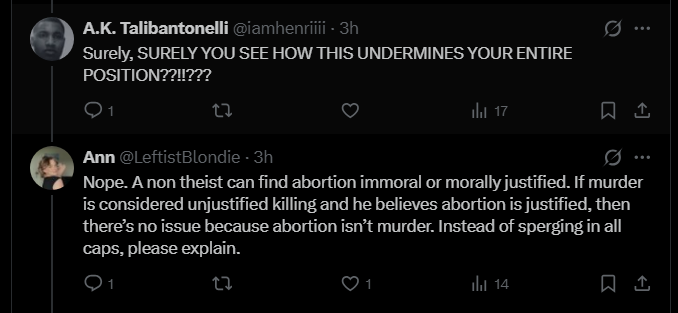

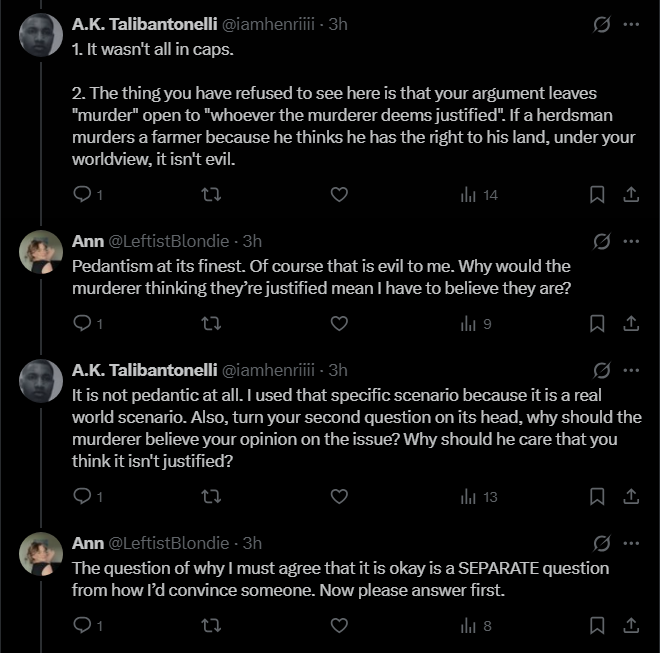

A.K. seems to believe Ann must judge that other people’s actions are not evil if those people endorse their own actions:

The thing you have refused to see here is that your argument leaves “murder” open to “whoever the murderer deems justified”. If a herdsman murders a farmer because he thinks he has the right to his land, under your worldview, it isn’t evil.

This does not follow. This remark seems to imply that Ann’s position is that if someone thinks an action is permissible, then it is permissible for that person to perform that action from Ann’s point of view or at least it’s “not evil” from Ann’s point of view. But this doesn’t follow at all. What A.K. seems to be describing sounds like some form of agent relativism, according to which whether an action is right or wrong can only be judged relative to the standards of the agent performing the action. But Ann does not endorse agent relativism (Ann explicitly confirmed this when asked). This person appears to have a misconception about Ann’s metaethical position.

Alternatively, A.K. may have in mind some form of antirealism according to which nothing is evil in the relevant sense; perhaps some form of noncognitivism or error theory. But Ann isn’t obligated to endorse these positions, either. Simply put, nothing about antirealism requires you to not think other people’s actions are “evil.”

However, here is the key remark:

It is not pedantic at all. I used that specific scenario because it is a real world scenario. Also, turn your second question on its head, why should the murderer believe your opinion on the issue? Why should he care that you think it isn’t justified?

Note how both questions presuppose that Ann thinks the murderer:

Should believe Ann’s opinion on the issue

Should care that Ann thinks their murder wasn’t justified

As such, these are technically complex questions. Complex questions are questions that include a presupposition that the respondent may not share. Such questions can be misused to make a respondent look evasive or to answer questions in ways that imply their acceptance of the presupposition. Sometimes one may simply grant the presuppositions, but in this case, antirealists shouldn’t do so.

Here’s why. This complex question is also tangled up with ambiguity:

What does the person posing the question mean by “should”?

Suppose you are an appraiser relativist. On such a view, your moral claims are reports of your own moral standards, so a statement like:

Murder is wrong.

means something like

I consider murder morally wrong.

or

I disapprove of murder.

Now, on such an analysis, the question A.K. is posing doesn’t make much sense. When Ann is asked why the herdsmen should believe Ann’s opinion, and why they should care that Ann thinks murder is not justified, what does “should” even mean in this context? For an appraiser relativist, normative moral terms like “should” are embedded in statements that implicitly index one or another different moral standards.

Nothing about appraiser relativism entails that one believes others “should” share your own values in any respect other than one might prefer that they do so. So if Ann were an appraiser relativist, to judge that others should believe Ann’s opinion or care that the murder in question is unjustified is just to judge that one would prefer or value that they do so. And if one does have such a preference, then it would be trivially true that they “should” believe Ann’s opinion and “should” care: all this amounts to is the recognition that Ann wants them to, which would be pretty easy to establish.

Alternatively, if the question is presuming some kind of stance-independent normative evaluative standard, then the question is presupposing something the appraiser relativist will probably reject: that there even is such a standard.

More generally, the question seems to rely on the presumption that antirealists will agree that other people “should” share their moral standards and “should” care what the antirealist themselves thinks. But antirealism doesn’t commit you to having a position on whether others should share one’s own moral standards or care what the antirealist thinks is wrong.

For some reason, critics of moral antirealism seem to think that antirealists believe that their moral standards should be relevant to others, and that we expect people to care about our moral values and have some motivation to comply with them. But we just don’t have to think this.

Antirealists should point out that this is a complex question and request that the people posing the question be clear about what they are asking. It may be difficult to do this without looking like one is trying to dodge the question, but such questions are misguided and useless at best, and outright misleading rhetorical tools that can dupe unwary audiences into thinking the antirealist’s position suffers from shortcomings it simply doesn’t have. I hope those who employ this strategy will recognize how hollow and misguided it is, and stop using it when arguing with moral antirealists.