If you're a subjectivist, then why do you care?

Twitter Tuesday #35

1.0 The stance-independence/scope conflation

Metaethical subjectivism is the view that moral claims are true or false relative to the standards of different individuals. In its most standard form, it is a form of moral antirealism according to which moral claims are made true by the moral standards of the agent making the claim (I’d call this individual stance-dependent appraiser relativism, if I wanted to be really specific).

For some reason, critics of subjectivism (or views adjacent to it; it’s often unclear what specific form of relativism or subjectivism people are talking about) often reason in the following sort of way:

If you think there are no objective moral standards, then why do you care what other people do? What’s the point in arguing with people, or raising objections to other people’s actions?

This doesn’t make much sense. The reasoning might go something like this. Consider your food preferences: perhaps you like chocolate ice cream more than vanilla ice cream. Do you care much what other people’s ice cream preferences are? You may under very peculiar circumstances. Suppose 99% of the world preferred vanilla over chocolate, and this made it difficult to obtain chocolate ice cream. In this case, we may suppose you care what other people’s preferences are because it impacts your ability to enjoy the food like you. But let’s suppose we’re dealing with a mundane situation in which another person’s food preferences have no direct, nontrivial impact on you (i.e., something like the circumstances of the world we’re actually in.) Would you care if someone else liked vanilla ice cream more?

My guess is that you probably wouldn’t. Furthermore, you may have little motivation to try to persuade someone who prefers vanilla over chocolate to prefer chocolate over vanilla. You may simply not care what they prefer and thus have no desire at all to even make an effort. But you may also think that food preferences aren’t the sort of things we can ordinarily change people’s minds about. Once again, this isn’t always true. If someone claims they hate certain foods, there are lots of situations where you may attempt to persuade them to give the food a try, or if they’ve tried it already, a second chance:

You believe they tried an especially bad version of the food, e.g., maybe they only had cheap, low-quality pizza. They may like higher quality pizza if they try it

They grew up eating a poor representation of a particular dish. Maybe a family member always prepared a squash casserole they found vile, so they come to believe that squash is disgusting. But actually it was only disgusting because the family member in question was a terrible cook

They never tried the dish in question. They’re disgusted by the idea of it, but if they could be persuaded to taste it, they’d change their mind

Even if you’re not a gastronomic realist that believes there are facts about what food is tasty or gross independent of anyone’s taste preferences, these examples illustrate that we might still care about other people’s food preferences and attempt to persuade them to try new foods. This illustrates that even in cases where people may not think the evaluative subject matter in question (i.e., food preferences) involve appeals to stance-independent normative facts about e.g., the intrinsic goodness or badness of food, we may still attempt to persuade others or care about what they do.

…But even if we completely set this aside, and deal with the totally typical, mundane case in which another person simply has a different, innocuous preference from our own, and we simply don’t care what they prefer to eat, this still reflects an important disanalogy to our moral values:

in these cases of differences in taste preferences, our evaluative standards only concern our own appraisals of the food in question: whether it tastes good to us. We may simply not care how it tastes to other people, since our goal is to enjoy food that we personally find tasty.

Morality typically isn’t like this. Our moral standards are rarely just standards of personal conduct. They could be. People sometimes commit themselves to personal moral standards with little or no expectation that others comply with these moral rules. A person may decide they will always tell their friends the truth, even if they don’t insist everyone act this way, including their own friends. Or a person may vow to perform a certain action, e.g., to visit their father’s grave. They may not think anyone else has an obligation to make similar vows, or expect them to, or judge them negatively if they don’t. So moral standards sometimes are very personal affairs, and have little or no implications for our attitudes about how other people act.

But the prototypical moral normative stance is a stance about how other moral agents (i.e., people capable of making moral decisions, which would exclude very young children, most or all nonhuman animals, etc.) ought to act. That is, we have desires, goals, values, preferences, and/or beliefs concerning not only our own conduct but the conduct we desire, expect, or demand of everyone. Compare these two standards:

Alex: I prefer strawberry ice cream. I do not care what other people’s ice cream preferences are.

Sam: I am against torturing people. I do not want anyone to torture others.

One difference between moral standards and taste preferences is that moral standards frequently involve attitudes or stances towards how other people act. We can think of this as the scope of a moral concern. The scope of an evaluative standard concerns who the standard is applicable to: is it only applicable to your own actions, or is it applicable to the actions of others? If you only include yourself in the scope of some normative stance, we can think of this as personal scope while if you include everyone, we could think of this as universal scope. Then there is everything in between: any scope that includes more than just yourself but less than everyone.

This difference is distinct from the distinction between moral realism and antirealism. Yet for whatever reason, people often conflate the two, and seem to believe that subjective moral standards are also limited in scope.

This may be because people make the even more common mistake of thinking that if two things are alike in one way, they must be alike in other ways. The similarity between moral subjectivism and taste subjectivism is simply that what makes one’s claims about what is morally good or bad, or gastronomically good or bad, is your stance on the matter. This has nothing to do with the scope of those standards: you can be a subjectivist and hold that:

Universal scope: You prefer that nobody harm others for fun

Personal scope: You prefer to eat strawberry ice cream, but don’t care what anyone else prefers to eat

Intermediate/limited scope: You prefer that your friends not play pranks on you, but don’t care what other friend groups do

For some reason, critics of subjectivism often fail to recognize this, and seem to think subjectivism commits you to only holding moral standards according to a personal scope. It doesn’t. What I find puzzling is that these kinds of conflations are frequent yet almost nobody ever takes the time to disentangle them.

2.0 Persuading others

Nothing about subjectivism prohibits you from including anyone or everyone in the scope of your normative moral stances: you can hold that nobody should steal (relative to my moral standards). If you have moral standards of this kind, then of course you care what others do…pretty much by definition. Having a moral standard like this more or less just is an instance of caring about what others do. This brings me to why this is a Twitter Tuesday. Recently, someone stated the following:

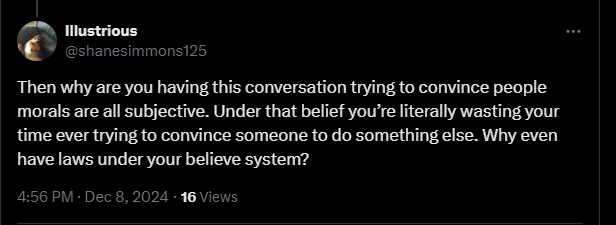

The person who posted this appears to believe that if someone holds a subjectivist stance about morality, that they’d be wasting their time trying to convince someone to do something (presumably in line with the subjectivist’s moral standards). They then suggest that there might not even be a reason to have laws if you’re a subjectivist.

If you hold the subjective moral standard that nobody should torture people why on earth would you be disinterested in persuading others not to torture people? You’re against them torturing people! Of course you’d want to persuade others!

They might also think that since you “only” have subjective moral standards, they must be limited in scope only to you. As I’ve already pointed out, this simply isn’t true.

They may also think that if you don’t think it’s stance-independently true that it’s wrong to do something, that you’d have “no reason” to oppose anyone who wanted to do that thing. This doesn’t make sense, because you can oppose them doing it because you don’t want them to do it. I don’t think there are stance-independent taste facts. That doesn’t mean I don’t care what food people serve me.

We simply do not need to think that there are stance-independent normative facts to get us to do things or abstain from doing things. We can do things or abstain from doing things simply because we want to. As far as I can tell, we already do this all the time outside the moral domain, so why would this somehow be necessary for the moral domain?

The same holds for the tweet’s suggestion that subjectivism would incline one to not care about having any laws. If you’re a subjectivist about food preferences, does that mean you shouldn’t care at all about the standards of restaurants or grocery stores? You should just not care if they keep food fresh and clean or stock high quality products? That wouldn’t make any sense: of course you’d care, because you want to eat food that you like. Having subjective preferences doesn’t somehow bar one from having a concern about standards or other people’s conduct or behavior.

Subjectivism is consistent with caring about how other people act, supporting laws, and otherwise acting in ways that are hard to distinguish from a commitment to moral realism. Moral realism simply adds this intermediary step.

Subjectivist antirealism: Personal moral values —> Actions

Realism: Belief in a particular set of stance-independent moral facts —> Personal motivation to comply with these facts —> Actions

Realists wouldn’t comply with stance-independent moral facts unless they valued, or wanted to do so (or otherwise felt compelled to comply with them). The subjectivist simply cuts out that first step, and acts on whatever their moral own standards are. We simply do not need to believe there are facts about some transcendent set of rules outside of our own standards and values and that we “must” conform with them in order to act on our goals and values, including goals and values related to other people act.

Moral realism about such matters strikes me as extremely weird. Why outsource your values in this way? Why would you comply with the moral facts, whatever they happen to be? What if they don’t accord with your personal values? Or do you just value whatever the stance-independent moral facts are, no matter what their content? That strikes me as incredibly weird, and part of the reason why Don Loeb’s gastronomic realism strikes so well for me: if on reflection the stance-independent gastronomic facts simply didn’t match my own taste preferences, why would I go ahead and eat food I didn’t enjoy? What would be the point?

Realists often frame antirealist positions as weird and psychologically bizarre. Yet if anything, realism is far stranger.

Are there any better or worse values/preferences to have? (If not “stance independently” then maybe relative to an idealized class of value-appraisers. That is, intersubjectively in a broad sense.)

If there aren’t any better or worse values to have in some extra-personal or extra-cultural sense, doesn’t this view entail relativism?

If morality (normative ethics) is any kind of coordination problem then that seems to be giving up on it on all but the most superficial level.