Illusionism, Bad Marketing, and the Nominal Fallacy

Twitter Tuesday #49

Illusionism is a position on the nature of consciousness according to which systematic and misleading introspective misrepresentations cause people to think they have phenomenal consciousness, but they are mistaken; there is no such thing as phenomenal consciousness. Or, in simpler terms:

People think they have phenomenal states (or qualia)

There are no phenomenal states (or qualia)

“Illusionism” is an unfortunate name. The name has prompted one of the laziest objections to a philosophical position. The criticism goes something like this:

Illusionism is self-defeating. According to illusionists, we are subject to the illusion of phenomenal consciousness. But in order to be subject to an illusion, you’d need to be phenomenally conscious! So it’s not possible for phenomenal consciousness to be an illusion. After all, if anything seems any way at all to you, then you’re phenomenally conscious, so phenomenal consciousness itself can’t be an illusion.

There are two straightforward responses to this objection:

First, it begs the question against illusionists by presuming that the only way one could be subject to an illusion is if they were phenomenally conscious of it. Illusionists are not obliged to agree that the only way one could be subject to an illusion is if they were phenomenally conscious of it.

Second, the position does not turn on the notion of an illusion in the first place. The illusionist can describe the position without any appeal to illusions. For instance, they can say that human minds are structured (or can be structured given appropriate experiences) to prompt people to make mistaken judgments about the nature of their consciousness. Notions such as belief, judgment, and so on don’t require the presumption of phenomenal consciousness.

The latter objection highlights how absurd this line of reasoning is. It’s as if critics think they can sink the position just by making uncharitable inferences entirely on the basis of the name of the position, as if the name and whatever assumptions one makes about the position on the basis of its name were somehow essential to the position. They aren’t.

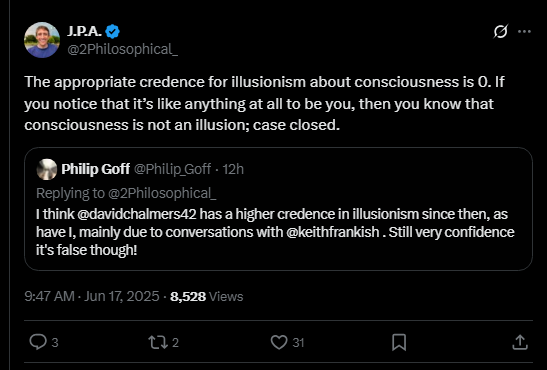

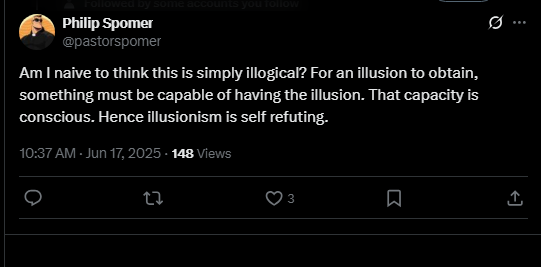

In case you think nobody actually makes this sort of objection, they do. Here are some examples:

This one is especially explicit:

Similar remarks have even been made by people in response to my blog posts:

These sorts of mistakes are even made by professional philosophers outside of more informal contexts like Twitter. Here’s a similar remark from Galen Strawson (2018):

One of the strangest things the Deniers say is that although it seems that there is conscious experience, there isn’t really any conscious experience: the seeming is, in fact, an illusion. The trouble with this is that any such illusion is already and necessarily an actual instance of the thing said to be an illusion.

This is especially absurd because of the inclusion of necessarily. It’s necessarily the case that if it seems to you that consciousness is a certain way, then you are phenomenally conscious? When was this established? How was this established?

Will Lugar helpfully provided an example in a published article as well, from Searle:

We cannot show that consciousness is an illusion like sunsets or rainbows because, where the very existence of consciousness is concerned, we cannot make the distinction between reality and illusion. If I consciously have the illusion that I am conscious, then I already am conscious. Traditional eliminative reductions rest on a distinction between reality and illusion, but where the existence of consciousness is concerned, the conscious illusion is itself the reality of consciousness. (Searle, 2007, p. 171)

This is ridiculous. The illusionist does not think that you are phenomenally conscious of the illusion that you’re phenomenally conscious. Instead, they’d either think you are conscious of the illusion in some non-phenomenal sense or that you are subject to the illusion without being “conscious” of it.

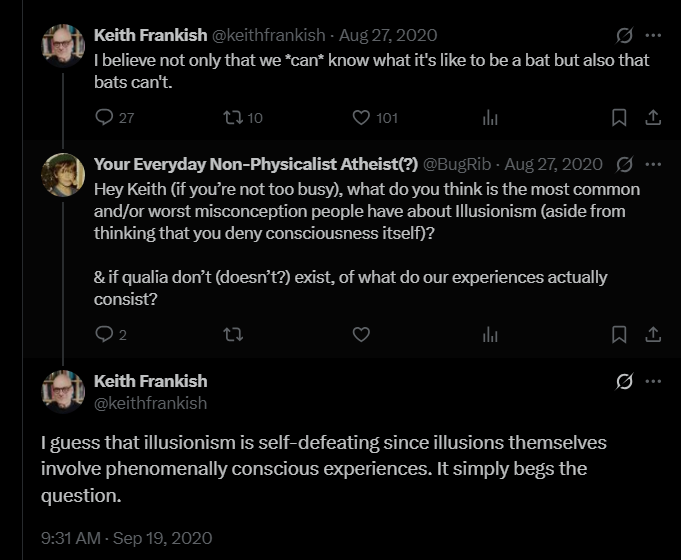

I’m not the first person to notice this bizarre, question-begging reaction to illusionism. Keith Frankish, a prominent contemporary proponent of illusionism, explicitly noted this himself. Have a look at this exchange from over five years ago:

Note that Keith Frankish considers the most common and/or worst misconception about illusionism to be the notion that it’s “self-defeating since illusions themselves involve phenomenally conscious experience” because it “simply begs the question.”

Frankish is right. It does beg the question. I don’t know exactly why critics raise such a lazy and weak objection against illusionism. Many critics of illusionism seem openly hostile and contemptuous of illusionism for reasons I still find mysterious. Others seem to not understand the position and appear dedicated to not doing so. I’ve discovered on more than one occasion that a critic of illusionism has never read Dennett’s work or appears to know little about the position. I have a dim recollection that I may have even encountered a person who doesn’t know who Dennett was and yet was aggressively denigrating illusionism.

Contempt for or ignorance of the position may account for some instances of this objection, though some may be committing a kind of nominal fallacy: the mistake of inferring what the position is on the basis of its name alone.

Nominal fallacy: The mistaken presumption that an accurate understanding of a concept, position, or phenomenon can be inferred from the name(s) or label(s) used to refer to it.

“Illusionism” is simply a cute name for the view. One can drop the notion of an illusion entirely and it would make no difference whatsoever to the content of the position. For instance, illusionism could be construed in terms that drop any reference to illusions and simply speak in functional, behavioral, or other non-phenomenal terms. We could rename the position, for instance, phenomenal error theory, or something like that, and restate the whole position without any reference to illusions. It would make no difference. I think reflexive hostility, dogmatism, intellectual laziness, and social forces (it’s rewarding to be part of a crowd that has already decided to publicly shit on the position) collectively account for much of the dismissiveness towards illusionism. This hostility is often so overt, and its proponents are often so open in patting one another on the back for their collective denigration, that it strikes me as a kind of diffuse bullying or social pressure by people who regard their position as being in the dominant position directed against a view with few defenders.

The kind of social pressure I’ve seen from academics and laypeople alike often seems intended to shame people with less popular views or encourage them to capitulate or shut up. Coupled with broad acceptance of mockery and insults directed at views and their proponents along with silly, asinine objections, the lazy, cliquish way philosophers denigrate certain philosophical positions has been one of my primary sources of disappointment with academia.

References

Searle, J. R. (2007). Dualism revisited. Journal of Physiology-Paris, 101(4-6), 169-178.

"the lazy, cliquish way philosophers denigrate certain philosophical positions has been one of my primary sources of disappointment with academia." It's almost as if philosophers first decided on opinions and then scrambled together arguments with whatever raw materials were close at hand to justify them! But that it would make philosophers into normal humans, not hyper-rational galaxy brains! Heresy, I say!

Nice! Think you got it exactly right.

I guess, though, that there are also non-intellectually-lazy people who think they've got sophisticated arguments for why illusionism is self-defeating. That argument certainly can be made lazily, but I wouldn't want to imply that it is always the case that such arguments are lazy. I don't think such arguments work, but (and perhaps you agree) I wouldn't want to assume that anyone trying to make such an argument is being lazy.

Now, you may ask me to provide an example of someone giving such a non-lazy argument from self-defeating, at which point I'll have to concede that I don't have one ready to hand.