The PhilPapers Fallacy (Part 1 of 9)

Table of contents

Part 2: Relevant expertise matters

Part 4: Selection effects matter

Part 5: How PhilPapers respondents interpreted the survey questions matters

Part 7: Philosophical fashions matter

Part 8: Demographic, social, and cultural forces matter

1.0 Introduction

Imagine we could survey every professional philosopher or person with a PhD in philosophy, and know exactly how they responded to a variety of questions about their philosophical views. This would provide us with a snapshot of the current patterns of belief among the relevant specialists.

Suppose we discovered that a majority of those surveyed endorsed a particular philosophical position. Perhaps 70% endorsed physicalism or 90% believed God didn’t exist or 96% thought two-boxing was the best solution to Newcomb’s problem. What should we make of these results? Should we conclude that if a majority of philosophers endorse a particular view, that this is evidence that this view is true? And that the stronger the majority, the stronger the evidence?

Yes.

We should take this to be some evidence that the views in question are true. However, such evidence may be qualified by a variety of considerations, and must be weighed against all the other evidence one has for and against a particular philosophical position.

We don’t have a survey like this. However, we do have the PhilPapers surveys. The latest (there have been two, one from 2009 and one from 2020) came out a few years ago. You can find the survey ,here.

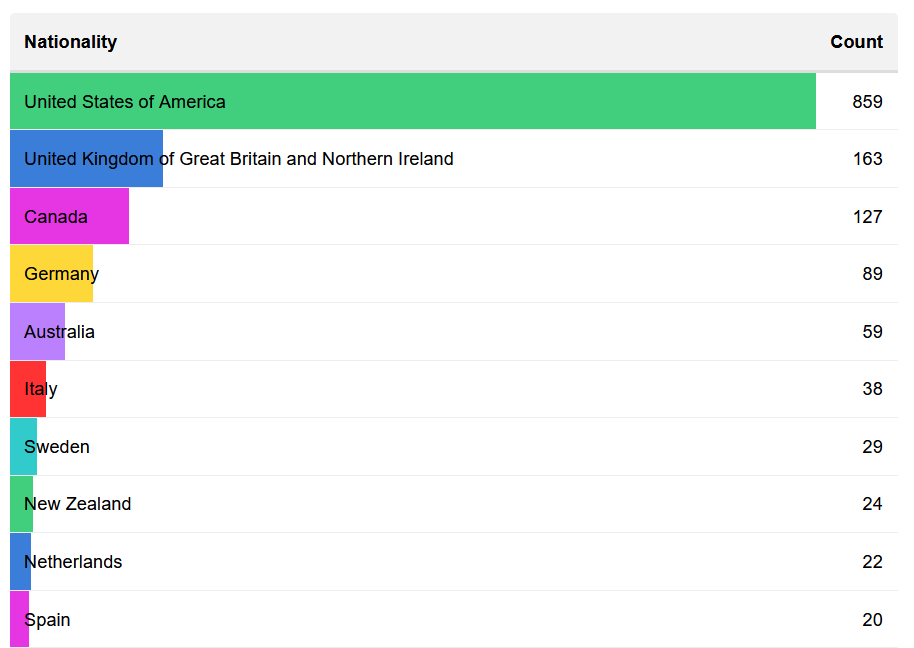

This survey doesn’t tell us what every philosopher thinks, just those that responded to the survey. The philosophers who responded to this survey may not generalize well to all philosophers, since the results are heavily skewed towards philosophers in the Anglophone world in particular. Of the ,1785 respondents, the following countries featured 20 or more respondents:

Note. PhilPapers 2020 Survey Results: Respondent Nationality.

As you can see, nearly half (~48%) are from the United States, while a majority are from the Anglophone world, including the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

The questions were also disproportionately based on the distinctions and interests characteristic of analytic philosophy in particular, and in particular a mainstream (and perhaps somewhat dated) conception of analytic philosophy. This is something the editors of the survey ,acknowledge:

Perhaps the most common objection to the 2020 survey was that the survey questions were strongly skewed to certain traditions and orientations in philosophy. Respondents from non-analytic philosophical traditions often reported feeling somewhat alienated by the questions, and even respondents from analytic traditions sometimes reported that the questions reflected a fairly traditional conception of philosophy that did not fully represent philosophy as it is done in 2020.

As I will argue, that the questions stem from and are framed in terms of a mainstream conception of analytic philosophy is itself a potential concern with respect to interpreting the results as evidence of the philosophical positions favored by the majority.¹

However, there are a variety of other concerns with appealing to the results of the PhilPapers survey as evidence for or against particular philosophical positions. Nevertheless, I routinely see people make appeals to the results of these surveys as evidence for or against a view. There is nothing necessarily wrong with this. If lots of smart people have thought about something for a long time, and reached a particular conclusion, then that should count as at least some evidence for that view.

The question is: how much?

I think the answer is: not much.

Those who appeal to the PhilPapers survey results often wield the endorsement of a majority as a bludgeon against those who hold less common views, a bludgeon used to stop conversations, or to argue that those who are confident in a view that most philosophers don’t endorse are arrogant, or not familiar with the topic, or are very unlikely to be correct.

An epistemically modest appeal to the proportion of philosophers responding to the PhilPapers survey as evidence for or against a philosophical position is fine. In fact, I think it’s great whenever philosophers appeal to empirical data rather than their intuitions. I complain often enough about ignoring relevant empirical data, and it’s better than appealing to anecdotes or hunches about what proportion of philosophers think about a given issue.

However, people often present PhilPapers survey results in ways that either (a) place greater epistemic weight on the results than is warranted or (b) appeal to them to enhance the credibility of a rhetorical move that would be empty without such appeals (e.g., an accusation of arrogance). Both are misuses of what could, in principle, be a reasonable appeal to empirical evidence in support for one’s views.

I call such misuses of PhilPapers day the Philpapers fallacy. I encourage others to do the same when they encounter misuses of appeals to the Philpapers survey results, or any similar claims or evidence about the alleged proportion of philosophers who endorse a view.

I should emphasize there is no bright line dividing cases where it’s legitimate to appeal to an authority from cases where it isn’t. Appeals to authority will serve as better or worse evidence depending on the claim in question, the authority in question, and various factors specific to the appeal in question. The Philpapers fallacy is reserved for appeals to the results of surveys about what philosophers think that overstate the strength of the evidence or otherwise leverage findings in objectionable ways.

Nevertheless, we should be extremely cautious of appeals to the survey results that indicate a particular proportion of philosophers who endorse a given view. There are several considerations that matter:

Relevant expertise matters

Causality matters

Selection effects matter

Interpretation of the PhilPapers questions matters

Independence matters

Philosophical fashions matter

Demographic, social, and cultural forces matter

Ultimately, mechanisms matter

Notes

Note that not everyone who responded to the survey regards themselves as an analytic philosopher. In fact, only about 80% did so (1430 out of 1785), with another ~6% (113) favoring continental philosophy and ~9.5% (169) reporting some other tradition. Note that 73 didn’t respond, and at least some of those could be analytic philosophers, and in any case even if one operates within another tradition that does not mean they weren’t exposed to or trained in analytic philosophy as well. Nevertheless, not everyone who responded to the survey is going to be all-in on analytic philosophy.