The presumption of folk moral realism must die

Twitter Tuesday #10

1.0 The presumption of folk moral realism

The belief that ordinary people think or speak like moral realists or experience morality in a way indicative of moral realism (i.e., moral considerations seem to concern matters of stance independent fact) is one of the most persistent articles of faith among contemporary analytic philosophers working in metaethics. Consider this remark from the philosopher J. P. Andrew:

Clearly there are objective moral values; it's a basic datum of experience.

No details are given about who it’s a basic datum of experience to. This remark strikes me a bit like saying “Clearly chocolate is tasty; it’s a basic datum of experience.”

Whether or not, and to what extent, something is a “basic datum of experience” for any particular person or proportion of people is an empirical matter. While one can readily report on their own experiences, we have no direct access to other people’s experiences. Knowledge of what other people’s experiences are like must be obtained experientially, through observation, discussion, psychological studies, and so on.

Many philosophers will claim that something “is intuitive” or that a particular type of experience is a sort of “datum” or make other general remarks about human psychology without being clear or precise about what exactly they mean, and, when such claims are made clear, they’re often highly speculative psychological claims that are not supported by available empirical data.

Imagine, for instance, if I said that “experience of the divine is a basic datum of experience.”

Have you had an experience of the divine? Some readers may report having had such experiences. Others won’t. What, exactly, does it mean to say something is a “basic datum of experience”? That everyone has it? Presumably not, but if so, then such claims are easy to refute. That some people have it? If so, then how many people? That people have these experiences under certain conditions? Well, that’s an empirical claim, and you’d need to show that people who meet these conditions and that those who don’t necessarily have the same experiences. And what are we to do with such remarks? If some unspecified number of people have religious experiences, but some other unspecified number of people don’t, do we privilege the former’s experiences over the latter? If so, why?

2.0 Scientific encroachment and WEIRD psychology

Philosophers often object to scientific encroachment on philosophical topics. Scientists may insist that in virtue of our knowledge of biology, psychology, or physics that free will doesn’t exist, or that we can dispense with the hard problem of consciousness, or that naturalist accounts of moral realism are true, and so on, without seeming to appreciate the philosophical issues they’re glossing over. Philosophers in these cases rightly object that many attempts by scientists to settle philosophical disputes by appeal to empirical findings are ill-conceived, confused, and often deeply misinformed about a whole host of potential complications and challenges to their claims.

Yet philosophers sometimes feel little or no compunctions against encroaching on scientific matters. Proponents of these claims may want to eschew empirical research. That’s fine, but personal experiences or familiarity with whoever you happen to have encountered in your life may or may not be representative of how most people think, and will not provide the kind of high quality evidence one would obtain if they were to gather evidence in a careful and systematic fashion.

For instance, people from WEIRD populations are psychological outliers with respect to the rest of the world’s population (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). Analytic philosophers who make such claims are typically members of WEIRD populations, mostly interact with people from WEIRD populations, and mostly studied the work of philosophers from WEIRD populations. Their familiarity with other cultural perspectives will often be heavily influenced by an almost exclusive exposure to an extremely parochial cultural perspective. They often have little or no substantive engagement with cross-cultural psychological research that could be relevant to such questions, and, in any case, there is so little research directly assessing cross-cultural variation in folk metaethics that even if one did make a study of it, they wouldn’t reach any conclusive answers.

Without substantive cross-cultural empirical research, how would Andrew know what populations outside those Andrew has primarily interacted with think about these topics? How many populations has Andrew interacted with? What do the Tsimane and Machigenga think about moral realism? When they make moral claims, do those claims appear to commit them to realism? Do they make moral claims? If so, what are some prototypical moral claims in the languages they speak? There are over 6000 languages in the world. How many of those languages is Andrew immersed in, to know what the structure of their moral claims (if they have them) look like, and how they function, not only in the abstract, but within the contexts of the cultures and populations that speak those languages? It’s not merely the case that psychological differences between WEIRD and non-WEIRD populations are attributable to enculturation alone, but language can facilitate or reinforce these differences. Consider this response from Majid and Levinson (2010) to Henrich et al.’s article:

The linguistic and cognitive sciences have severely underestimated the degree of linguistic diversity in the world. Part of the reason for this is that we have projected assumptions based on English and familiar languages onto the rest. We focus on some distortions this has introduced, especially in the study of semantics.

Earlier work from Evans and Levinson (2009) argues that there is little evidence to support the notion of linguistic universals. Philosophers may be content to presume that the fundamental structure of language is highly convergent around the world. It isn’t. And, as the authors argue that

[...] semantic variation seems to correlate with psychological variation on a range of parameters. As a result, most of our ideas about how humans reason or what notions form natural categories are prompted by our own languages. (p. 103).

The analysis of moral claims in the English language in particular is central to much, if not most of the descriptive project of contemporary analytic metaethics. So we have a twofold problem here: contemporary analytic philosophy draws on the considered judgments not only of an extremely psychologically unrepresentative population as a result of broad cultural differences, it also focuses almost entirely on the analysis of words and sentences in English, which may or may not reflect the way people in the 6500 or so other languages around the world are disposed to speak.

If Andrew has primarily operated within WEIRD societies, and writes, reads, speaks, and mostly interacts with people in English, it’s likely Andrew’s interactions, primary language or languages, and so on all fall within the ambit of a distinctively WEIRD cultural milieu. If so, then Andrew may be familiar with the way a psychologically idiosyncratic population thinks about these matters, a population whose members have already been shown to vary in multiple ways from other populations with respect to moral reasoning and a variety of judgments relevant to morality, e.g., attitudes, prosociality, fairness, and cooperation (Henrich et al., 2006; 2010).

Most psychological research has been conducted on college students and people in WEIRD populations. Yet when similar studies are conducted among other populations, researchers routinely find that people in other populations often differ, and the populations that figure into most of our psychological research often anchor one or the other extreme end of the distribution when comparing data across different populations. Indeed, not only are WEIRD populations psychological outliers, people from the United States are at the extreme end of WEIRD populations.

In the previous section, we discussed Herrmann et al.’s (2008) work showing substantial qualitative differences in punishment between Western and non-Western societies. While Western countries all clump at one end of Figure 4, the Americans anchor the extreme end of the West’s distribution. (Henrich et al., 2010, p. 75)

To illustrate this anchoring effect, here is a graph Henrich and colleagues provide that illustrates the amount of money offered in a dictator game across 15 societies:

If your goal was to conduct studies on a population and then generalize to the rest of humanity on the basis of those results, people in the United States would be one of the worst possible options. And note such studies concern real-world practical indicators of prosocial behavior, a matter deeply relevant to moral judgment. These differences are so broad in scope and have so great an influence on human psychology that cultural and linguistic differences even influence spatial cognition. And, once again, people from WEIRD populations are psychological outliers:

[...] it appears that industrialized societies are at the extreme end of the continuum in spatial cognition. Human populations show differences in how they think about spatial orientation and deal with directions, and these differences may be influenced by linguistically based spatial reference systems. (p. 68)

This indicates how, even when we systematically gather empirical data, we can still lack adequately representative data about how the rest of the world thinks.

Yet Andrew seems to believe we can make inferences about people’s experiences without appealing to systematic empirical data (or at least, Andrew doesn’t present any). Simply put: that something seems obvious to a philosopher, or even many of the people they’ve interacted with, is not a good reason to presume it’s a basic feature of human experience. Some cultures may have and report basic features of their experiences that other cultures don’t report. The only way to find out is to conduct cross-cultural empirical research.

Matters are worse than this, however. It would be bad enough if we sought to generalize from systematic and carefully designed studies conducted on representative US populations to the whole rest of the world. We’d already be wrong (possibly even probably wrong) about what most people think in such cases. Yet analytic philosophers don’t even typically appeal to this sort of data. Instead, they appeal to their personal experiences and interactions with others, which will be unavoidably skewed towards people more disposed to think the way they do.

Why is that a problem? Because philosophers are even more idiosyncratic, since they represent an exceptionally narrow and insular community who, in virtue of their education in a narrow, homogenous, predominantly Western canon of work, are virtually defined by induction into and further reinforcement of distinctively WEIRD ways of thinking.

Psychologically speaking, analytic philosophers who received their education in the United States and work in the United States are outliers among outliers among outliers. Yet people from such populations believe they believe they can extrapolate from the way they think to the way everyone else thinks without doing any of the empirical work necessary to do so. This is, in a word, preposterous.

Contemporary analytic philosophers persist in the implausible presumption that their intellectual faculties somehow transcend the parochial enculturation that has shaped the way they think, despite growing evidence that most of them tend to operate within one of most psychologically unrepresentative societies in the world, a population that not only differs markedly from most extant populations, but very likely from historical populations as well.

3.0 There is little evidence that almost everyone is a moral realist and some evidence many are not

Of course, none of these considerations directly address whether empirical evidence supports the contention that a notion of “objective moral values” are a “basic datum of experience.”

Research in the psychology of metaethics does not support these claims. In fact, it’s not at all clear that this claim is true even within WEIRD populations. I don’t have these experiences. And when researchers have constructed various means of evaluating people’s metaethical views, they routinely find that many nonphilosophers favor moral antirealist views. For instance, look at the rate of antirealist responses in this study:

3.1 Pölzler & Wright (2020b)

(Pölzler & Wright, 2020b, Fig. 1, p. 75)

3.2 Davis (2021)

Consider antirealist rates in this study, across a variety of moral domains:

(Davis, 2020, Fig. 5, p. 21)

3.3 Collier-Spruel et al. (2019)

This study found that the average score on a variety of questions assessing support for metaethical relativism was around the midpoint:

(Collier-Spruel et al., 2019, Fig. 1, p. 14)

3.4 Zijlstra (2023)

A study from Zijlstra (2023) employed three novel paradigms, which were intended to test Enoch’s (2024) three proposed methods of testing whether people are disposed towards moral realism. Zijlstra reports that, “Overall, results provide support for the idea that people are moral objectivists.” However, if you look at the results of the studies, the findings were far more equivocal than this, and at best only found a modest majority in favor of realism.

Enoch (2014) employs three tests: a joke test, a phenomenology test, and a counterfactual test.

With respect to the “joke test,” participants are expected to judge an attempted joke about taste preferences to be a joke, but to not judge a similar attempt at a joke about morality to be a joke. Quoting Enoch:

[i]f the joke works, this seems to indicate that the subject matter is all about us and our responses, our likings and dislikings, our preferences and so on. If the joke doesn’t work, the subject matter is much more objective than that, as in the astronomy case (Enoch, 2014, p. 193-194, as quoted in Zijlstra, 2023, p. 233)

In other words, judging the moral scenario to be a joke would be inconsistent with an implicit commitment to realism. Yet 32% of the participants did judge the moral scenario to be a joke. At best, then, perhaps two thirds of participants may respond in a way that hints at realism. This is nowhere near some kind of overwhelming majority.

The phenomenological test asked participants whether moral disagreements felt more like disagreements about whether bitter or milk chocolate is better, or a disagreement about whether humans contribute to global warming. In this case, 77.5% of participants chose the latter, suggesting that they treat moral disagreements as disagreements about matters of fact. There are numerous methodological concerns with these findings, and I question whether they provide any strong indication one way or another about whether participants are implicit realists or antirealists. However, note that, yet again, a substantial subset of participants didn’t favor the realist response.

However, the matter is more complicated than this. Zijlstra also conducted three additional tests that varied the stimuli used for the phenomenology task. Where were the realist responses for these:

28.1% realist response

45.7% realist response

27.7% realist response

The unweighted average realist response rate across all four conditions is about 45%. These results are hardly an indication that an overwhelming majority of people have realist phenomenology. This is perhaps the most important lack of a decisive form of evidence for the remark that prompted this post, because this particular test concerns phenomenology, just as Andrew’s original remark did.

Zijlstra’s last study found 70% of participants favored the realist response. Once again, even if the measures in question were capturing people’s metaethical views (I am skeptical that these or any other studies are interpreted by participants as intended), this would only indicate a majority of participants favor realism, but not an overwhelming one. 30% is no small proportion.

Overall, then, even studies that purport to show that people are objectivists only show that, at best, with respect to some measures, around two thirds to three quarters of people may be disposed towards realism. We’re not talking 95%, or 99% or anything even close to that.

3.5 Pölzler, Zijlstra, and Dijkstra (2022)

Finally, Pölzler, Zijlstra, and Dijkstra (2022) draw a distinction between five positions ordinary people may hold towards moral claims:

(1) INDEPENDENCE: People believe that moral sentences are true or

false independently of anyone’s subjective reactions or attitudes.

(2) EXCLUSION: People believe that only one party in a moral disagreement can be correct.

(3) PROGRESS: People believe that it is possible to make moral progress.

(4) KNOWLEDGE: People believe that it is possible to have moral knowledge.

(5) ERROR: People believe that it is possible to make moral mistakes. (p. 2)

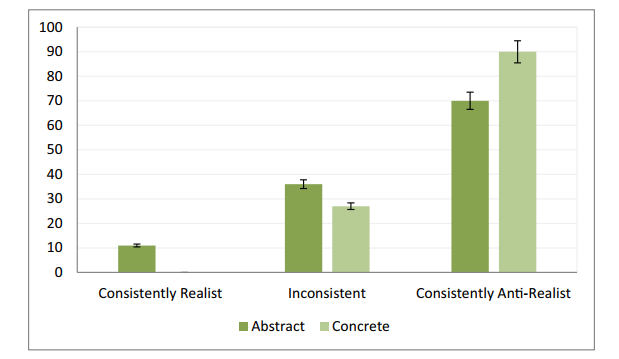

The note that most studies have addressed (1) and (2), but few have addressed (3) PROGRESS, (4) KNOWLEDGE, or (5) ERROR. They constructed a new set of paradigms to assess these indicators of folk moral realism which tested people’s metaethical standards using a combination of both abstract and concrete measures. What did they find? Here you can see the total percentage of participants who favored the realist response option across paradigms:

These findings indicate that, overall, a majority of participants rejected a realist conception of moral progress, moral knowledge, and moral error. Is this definitive evidence that many people are not moral realists?

I don’t think it is. However, what we don’t have is a comparably diverse set of paradigms like those I have canvassed here that show overwhelming evidence that ordinary people are moral realists.

Unless I’m concealing the fact that there’s a whole host of studies that provide really robust evidence to the contrary (I’m not; I’ll append this post with a bibliography of studies on the psychology of metaethics and encourage everyone to go check these studies out), these are not the kinds of results we should be obtaining if it were so clear that pretty much everyone is a moral realist, at least not if it were so clear to the people routinely participating in these studies: college students and people from the United States.

One might balk at the limited generalizability of these populations, but note that most philosophers who insist most people are realists are themselves primarily interacting with college students and people in the United States as well. If these studies lack generalizability in a way that undermines the degree to which they represent evidence of how people in general think, this is even more true of the personal experiences of analytic philosophers who come from WEIRD nations, were trained in philosophy in them, or mostly interact with people from such populations. As such, concerns about the generalizability of tested populations are cold comfort to armchair philosophical claims about folk metaethics.

If philosophers are mistaken about the metaethical views even of the people around them, it is hard to imagine why they’d be much better at assessing the metaethical views of people from societies they’re not part of or as familiar with.

Do some studies find higher rates of realism? Yes. Studies evaluating the metaethical views of children appear to exhibit higher rates of moral realism; see e.g., Nichols & Folds-Bennett (2003) and Wainryb et al. (2004). Some early studies also reported higher realist response rates, or much more mixed responses, such as Goodwin and Darley (2008) and Wright, Grandjean, and McWhite (2013).

These findings are not exhaustive, by any means. There are now a few dozen studies that measure people’s metaethical views. Some lean more towards most people being realists, while others lean towards most people being antirealists, and yet others (myself included) favor other alternatives (in my case, metaethical indeterminacy). I can’t think of a single study where even 90% of participants favored moral realism with (perhaps) the exception of Wainry et al. (2004). However, this study was conducted among children, and there are good reasons to worry about the methodology for this study as well. That isn’t to say there aren’t others; only that to anyone familiar with the empirical literature, we are generally aware that the results do not suggest some kind of overwhelming univocality among participants in favor of realism. However, even people in the field have commented on how earlier studies overstated the case for folk realism (Pölzler, 2017) and cataloged extensive methodological problems with these studies (Bush & Moss, 2020; Pölzler, 2018).

Researchers who have conducted studies in the field or commented on the literature (or both) have often regarded the data as supporting conclusions that do not neatly fit with the notion that moral realism is “the” commonsense position or that most people are disposed towards moral realism, including Beebe (2020), Bush and Moss (2020), Colebrook (2021), Pölzler & Wright (2020a; 2020b). At present, no reasonable reading of the overall body of research on the psychology of metaethics could lead anyone to justifiably conclude that we have good evidence almost everyone is disposed towards moral realism. The evidence for this simply isn’t there. Indeed, it couldn’t be there simply because we do not have sufficiently generalizable findings to tell us what most of the world’s population thinks about these sorts of issues.

At best, some studies find a significant majority of participants in favor of realism, but such majorities are typically below 80% and are no more representative than studies that find a majority in favor of antirealism (For what it’s worth, studies that are finding majority antirealism tend to be more recent, reflect a broader range of paradigms, and tend to have corrected on some of the methodological shortcomings of earlier papers). But this is not as strong a claim as claiming that people have realist phenomenology. There are few if any studies (aside from Zijlstra’s) that address this question. And Zijlstra found that, out of four sets of stimuli, participants favored antirealism in three of them, and antirealism still made up nearly a quarter of participants in the fourth.

Philosophers may question the validity of these studies. They should. I certainly have: my dissertation is a methodological critique of the validity of these studies. But note that the absence of valid measures simply results in us not knowing what proportion of people (if any) are moral realists. What we do not have is a robust and compelling literature that seems to be converging on the conclusion that an overwhelming majority of people have realist phenomenology, are disposed to think or speak like realists, speak like realists, and so on.

I cannot emphasize this strongly enough:

At present, we do not have anywhere near sufficient evidence to support the claim that people are generally disposed towards moral realism. At the moment, the most well-designed studies routinely find very high levels of antirealism, in some cases even comprising the majority of participants.

4.0 Conclusion

Though the persistence of the presumption in favor of realism frustrates me in no small part because I think it’s probably false, I know that most philosophers don’t share my perspective on this matter. However, in this case, the matter in question is an empirical one: how do nonphilosophers think about metaethical questions, what is their experience of morality like, and so on. These are questions that fall more within the ambit of psychology than philosophy. It may be reasonable for philosophers to dismiss overconfident and uninformed philosophical perspectives from scientists. Unfortunately, philosophers do not seem to respect this boundary in the other direction, and fail to recognize that they, too, are capable of making overconfident and uninformed claims about the sciences. The presumption that most people experience the world like moral realists is one such example.

I hope those philosophers who believe most people think, speak, or act like realists, or have realist phenomenology, will reconsider that position and have a look at some of the research I’ve described here.

References

Beebe, J. R. (2020). The empirical case for folk indexical moral relativism. In T Lombrozo, J. Knobe, & S. Nichols (Eds.), Oxford studies in experimental philosophy (Vol. 4, pp. 81-111). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Berniūnas, R. (2020). Mongolian yos surtakhuun and WEIRD “morality”. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science, 4(1), 59-71.

Bush, L. S., & Moss, D. (2020). Misunderstanding metaethics: Difficulties measuring folk objectivism and relativism. Diametros 17(64): 6-21.

Colebrook, R. (2021). The irrationality of folk metaethics. Philosophical psychology, 34(5), 684-720.

Collier‐Spruel, L., Hawkins, A., Jayawickreme, E., Fleeson, W., & Furr, R. M. (2019). Relativism or tolerance? Defining, assessing, connecting, and distinguishing two moral personality features with prominent roles in modern societies. Journal of Personality, 87(6), 1170-1188.

Davis, T. (2021). Beyond objectivism: new methods for studying metaethical intuitions. Philosophical Psychology, 34(1), 125-153.

Dranseika, V., Berniūnas, R., & Silius, V. (2018). Immorality and bu daode, unculturedness and bu wenming. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science, 2, 71-84.

Enoch, D. (2014). Why I am an objectivist about ethics (and why you are, too). In R. Shafer Landau (Ed.), In the ethical life: Fundamental readings in ethics and moral problems (pp. 192-205). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Henrich, J., Ensminger, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., Cardenas, J. C., Gurven, M., Gwako, E., Henrich, N., Lesorogol, C., Marlowe, F., Tracer, D. P. & Ziker, J. (2010). Markets, religion, community size, and the evolution of fairness and punishment. science, 327(5972), 1480-1484.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83.

Henrich, J., McElreath, R., Ensminger, J., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., Cardenas, J. C., Gurven, M., Gwako, E., Henrich, N., Lesorogol, C., Marlowe, F., Tracer, D. & Ziker, J. (2006) Costly punishment across human societies. Science 312(5868):1767–70.

Majid, A., & Levinson, S. C. (2010). WEIRD languages have misled us, too. [Commentary on Evans & Levinson, 2009]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 103-104. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1000018X

Nichols, S., & Folds-Bennett, T. (2003). Are children moral objectivists? Children's judgments about moral and response-dependent properties. Cognition, 90(2), B23-B32.

Pölzler, T. (2017). Revisiting folk moral realism. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 8, 455-476.

Pölzler, T. (2018). How to measure moral realism. Review of philosophy and psychology, 9, 647-670.

Pölzler, T., & Cole Wright, J. C. (2020a). An empirical argument against moral non-cognitivism. Inquiry, 1-29.

Pölzler, T., & Wright, J. C. (2020b). Anti-realist pluralism: A new approach to folk metaethics. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 11, 53-82.

Pölzler, T., Zijlstra, L., & Dijkstra, J. (2022). Moral progress, knowledge and error: Do people believe in moral objectivity?. Philosophical Psychology, 1-37.

Wainryb, C., Shaw, L. A., Langley, M., Cottam, K., & Lewis, R. (2004). Children's thinking about diversity of belief in the early school years: Judgments of relativism, tolerance, and disagreeing persons. Child Development, 75(3), 687-703.

Wright, J. C., Grandjean, P. T., & McWhite, C. B. (2013). The meta-ethical grounding of our moral beliefs: Evidence for meta-ethical pluralism. Philosophical Psychology, 26(3), 336-361.

Zijlstra, L. (2023). Are people implicitly moral objectivists?. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 14(1), 229-247.