What is metaethical relativism?

1.0 What is metaethical relativism?

Metaethical relativism (or just “relativism”) is a philosophical position according to which the truth of moral claims can only be judged relative to one or another of multiple, distinct standards. Typically, these are either the standards of individuals or cultures.

Like other metaethical positions, relativism takes a position on the meaning of ordinary moral claims. An ordinary moral claim is not a mysterious or technical notion. It is simply the sorts of claims people would make in everyday circumstances about what is morally right, wrong, good, bad, permitted, prohibited, and so on. Philosophers typically give prototypical examples of moral claims like this:

“It is morally wrong to get an abortion.”

“It is morally obligatory to take care of your children.”

Notice that these sentences are a bit stilted and unnatural. In everyday language, you might instead hear things like:

“He stole a car?! He should get locked up!”

“Anyone who is cruel to animals is a trash human being.”

“Prolifers are scumbags.”

“You can’t trust nonbelievers, since they don’t believe they are accountable to a higher power.”

Notice that everyday moral language involves slang, is often harsh, and often doesn’t explicitly reference morality. In addition, it often focuses not on the actions themselves (lying, stealing, etc.) but on the character of the people performing the actions, or the people who support performing those actions. While the examples I gave are, of course, made-up, they still reflect a common disconnect between philosophical discussion about “moral language” and the reality of actual moral language as studied by psychologists (Pizarro & Tannenbaum, 2012).

2.0 Indexicality

According to relativists, moral claims contain an indexical element (which may be implicit) that allows the truth status of a moral claim to vary in accord with who is making the claim (Joyce, 2007).

What is an indexical? Indexicals are linguistic expressions that allow the meaning of an utterance to vary depending on its context of usage by varying what the speaker/writer is referring to. Standard indexicals include “I,” “you,” and “me”, as well as terms like “this,” and “that” (I am sure you can think of more).

This indexicality is implicit in that it is not represented by an explicit use of indexical phrasing. Suppose someone were to try a slice of pizza at a new pizza place and exclaimed:

“This pizza is delicious!”

Now ask yourself how this person would respond to the following question:

“If someone else tried this pizza, but did not find it delicious, would they be mistaken?”

Aside from the fact that this person might say something like “What are you talking about? Leave me alone, I’m trying to enjoy this pizza,” were they to seriously entertain the question they may very well say “no.” Why? One reason could be that they do not think that their remark about the pizza being delicious was a statement about some intrinsic property of the pizza. In other words, it would not be like picking up a rock and saying “This is a piece of quartz.” After all, if it is a piece of quartz, and someone else picked it up and said “No, this is a piece of basalt,” they would be incorrect. So what did our pizza lover mean? They might say something like:

“I only meant that I found the pizza to be delicious.”

If this is what they meant, then this gives us all the tools we need for understanding how an implicit indexical works. When this person initially said “This pizza is delicious!” they meant something like:

“This pizza is delicious [to me].”

Or

“[I find that] this pizza is delicious!”

Note the use of the terms “me” and “I” here: they are indexicals. They were implied but not explicitly stated. Relativists about morality hold that moral claims are used in much the same way. They, too, express something about the speaker’s standards, or the standards of the speaker’s culture. So a moral claim like:

“Lying for personal gain is wrong” can be understood to express something like:

“[I am opposed to] lying for personal gain”

“Lying for personal gain is wrong [according to my/my culture’s moral standards]”

“Lying for personal gain is [inconsistent with my values]”

3.0 Individual & Cultural Relativism

There are, of course, other distinctions to be made. First, there is the question of which standard a moral claim is relativized to. Most of the time this is either the standards of individuals or the standards of cultures. There is little consistency with the former, but we may call it individual subjectivism, or individual relativism (or just “subjectivism”). The latter is almost always called cultural relativism.

Individual relativism

The truth of a moral claim can only be judged relative to the standards of different individuals.

Cultural relativism

The truth of a moral claim can only be judged relative to the standards of different cultures.

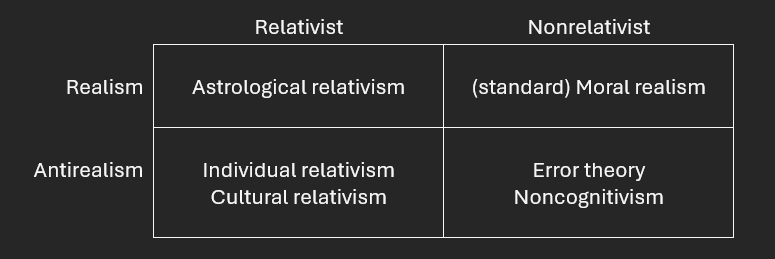

Technically, moral claims could be judged relative to other standards, such as the standards of different species (e.g., humans). In fact, it is even possible to relativize moral standards to something other than the values of individuals or groups. This brings us to an important, though often overlooked fact about moral relativism: moral relativism is not necessarily inconsistent with moral realism. Let’s define moral realism and its negation, moral antirealism:

Moral realism

The position that there are stance-independent (or “objective”) moral facts.

Moral antirealism

The position that there are no stance-independent (or “objective”) moral facts.

What does “stance-independent” mean? It means that the truth of the claim in question is not made true by a stance. Consider the following statements:

“I like pineapple on pizza.”

“Carbon atoms have six protons.”

The statement about pineapple on pizza would only be true if you did, in fact, like pineapple on pizza. It is made true by your preferences. The second statement, however, is not. Whether carbon atoms have six protons or not does not depend on your preferences. If you preferred carbon atoms have 22 protons or 4 protons or no protons at all, this wouldn’t change how many protons they have (Note: I am presenting this distinction and these examples as facts, though it is possible in principle for people to disagree, and either believe both claims are relative or neither are).

Given this distinction, we can now see why moral relativism is consistent with moral realism. Antirealists hold that there are no stance-independent moral facts. To be an antirealist, you could instead hold that there are no moral facts at all, or that there are stance-dependent moral facts, i.e., facts about what is morally right or wrong that are true, but their truth depends on a stance. Both individual relativism and cultural relativism are forms of antirealism not because they are relativistic, but because the truth of moral claims depends on stances, either of individuals or of cultures.

However, it is possible to relativize moral standards to something other than a stance. To provide one (possibly humorous) example, you could hold that different moral standards apply to different people depending on their astrological signs. Perhaps it is permissible for Geminis to lie, but if you’re a Taurus, you are prohibited from lying. On such a view, the truth of a moral claim would be indexed to different moral standards, such that if a person were to say “It’s okay to steal,” whether this is true or false would depend on whether they were a Gemini or were referring to the actions of a Gemini. I’ve never heard of anyone holding a position like this, but the point is simply that it is possible.

Conversely, you could reject moral realism but not be a relativist. There are many ways to do this. Here are the two most common:

Error theory

All moral claims about what is right, wrong, good, bad, and so on are false. Typically this is because all such claims are implicitly committed to a false presupposition (e.g., all moral claims express God’s will. If God does not exist, all such claims are false).

Noncognitivism

Moral utterances do not make truth claims at all. Instead, they express nonpropositional content (content that does not attempt to assert anything true or false).

However, you could believe that there are stance-dependent moral facts, but that these facts do not vary from one person to another. Suppose you believed that moral facts depended on God’s preferences, and there is only one God. In this case, moral facts would be stance-dependent (so you’d be an antirealist), but nonrelative (their truth does not vary depending on which standard is being relativized to, since there’s only one standard). One position in the literature that exemplifies this view would be ideal observer theory:

Ideal observer theory

There is a single set of moral facts which reflects the standards of an ideal observer, a being that is fully informed and perfectly rational (i.e., without any bias).

This distinction is rarely discussed. It is subtle and perhaps a bit confusing. For a source that discusses this distinction, see here.

4.0 Agent & Appraiser Relativism

Another important and overlooked distinction is the difference between agent and appraiser relativism. Note that this distinction is consistent with the individual/cultural distinction, such that you could be an agent individual relativist, an agent cultural relativist, an appraiser individual relativist, or an appraiser cultural relativist (and you could likewise apply the agent/appraiser distinction to any other standard of relativization besides individuals and cultures):

Agent relativism

The truth of a moral claim is judged according to the standards of the agent performing the action (or the standards of that agent’s culture).

Appraiser relativism

The truth of a moral claim is judged according to the standards of the agent evaluating the action (or the standards of that evaluator’s culture).

There is an important distinction here. When a person makes a moral claim, a relativist will recognize that the claim in question is implicitly indexed to some standard or other. The truth of that claim is determined by whether the statement is consistent with the standard in question. Suppose Alex considers it morally acceptable to steal, says:

Stealing isn’t morally wrong.

…then proceeds to steal something.

Sam comes along and hears Alex say it’s not wrong to steal, and then steal something. How do these two forms of relativism assess the truth of Alex’s claim? On both accounts, Alex’s statement means something like:

I consider it morally acceptable to steal.

…and on both accounts, this statement is true. Alex does consider it acceptable to steal, and so the statement is true because it is indexed to Alex’s standards.

However, the critical difference is that as an agent relativist, you yourself are obliged to judge whether it is right or wrong for Alex to steal on the basis of Alex’s standards. If Alex thinks it’s not wrong to steal, then it isn’t wrong for Alex to steal, full stop. That is, any outside evaluator must accept that it is morally permissible for Alex to stela. Agent relativism thus “fixes” the rightness or wrongness of an action by the standards of the agent.

If you’re an appraiser relativist, things get a bit more complicated. Alex’s statement is true, since it is indexed to Alex’s own standards. But as an appraiser relativist, judgments about whether an action is right or wrong are not made on the basis of the standards agent performing the action, even if the statements made by that agent, insofar as they are indexed to that agent’s standards, are true. Instead, the appraiser relativist judges whether an action is right or wrong on the basis of their own standards. As such, the appraiser relativist is committed to judging whether it is morally wrong for Alex to steal by appeal to their own standards.

As such, agent and appraiser relativism are best construed as accounts of how we judge moral actions, not as accounts of how we assess the truth of moral claims. In practice, all instances in which a person is making a moral claim will tend to be accompanied by a judgment about the rightness or wrongness of the act in question. Both agent and appraiser relativists can assess whether the statements people make are true in the same way: by allowing the context to determine the referent of the implicit indexical, i.e.:

Alex: Stealing is wrong

…is implicitly indexed to Alex’s standards, amounting to the statement:

Alex: I consider stealing wrong.

Both accounts should regard this statement as true, since in this case the agent and the evaluator are one in the same. But whereas the agent relativist is committed to judging the moral status of stealing by the standards of agents engaging in the action, the appraiser relativist dissociates their evaluation of the action from the agent performing it, and instead judges the rightness or wrongness of each agent by their own standards.

One common criticism of “relativism” is that it requires you to tolerate other people’s actions, even if they conflict with your own, and that you must condone or abstain from interfering when people steal or do even worse things. As you can see from these definitions, this is (at best) only true of agent relativism, not appraiser relativism. In practice, most critics of “relativism” only target agent relativism, and almost never mention appraiser relativism. This might be because they aren’t aware of the distinction. But it is suspiciously convenient that many critics focus on the form of relativism most subject to a rhetorically powerful objection.

In fact, there are many popular objections to relativism that are similarly misleading or downright false. Many philosophers seem to have it out for relativism. The philosopher Mike Huemer even has a section in one of his books that states that he hates relativism. I can’t do much about people hating relativism, but much of that hatred appears to be rooted in misunderstandings of the position. Regardless of whether you walk away from this class accepting, rejecting, or having no definitive position on relativism, I’d like you to be aware of all the reasons you shouldn’t reject the position. Here, we will cover some of the most prominent. Note that while some of these are mistakes that any reasonable person should agree with, some are more contestable, and at least some (if not many) academics would disagree with the assessment offered here.

[This section was edited on 12/17/2025 at 2:37 PM ET. Thank you to Randomize 12345 for the critical feedback.]

5.0 Normative and Descriptive Relativism

Metaethical relativism is sometimes conflated with two other notions, neither of which reflects a genuine metaethical position:

Descriptive relativism

The empirical position that there are widespread and fundamental differences in the moral values of different individuals or cultures.

Fundamental differences in moral values are differences that are due to a commitment to conflicting moral standards, and not due to a difference in nonmoral belief. For instance, there could be two individuals or cultures in which everyone agrees you should employ the method of punishment that most effectively deters crime. In one culture, they may practice executions but not in the other because the culture practicing execution believes it is the best way to deter crime, and the culture that doesn’t practice it thinks it isn’t an effective way to deter crime. If the society that practiced execution were given convincing evidence it wasn’t an effective deterrent, they’d stop the practice. In this case, both societies have the same fundamental moral standards, but implement different moral practices out of differences in their nonmoral beliefs. If everyone shared the same fundamental values in this way, descriptive relativism would be false.

A fundamental difference in moral value would be one that isn’t attributable to differences in nonmoral beliefs. If Alex believes it is good to punish criminals as an end in itself, and Sam thinks it is only permissible to do so for the positive consequences this yields to that person and society, and these moral values are not the result of a commitment to a deeper and more foundational moral value, then they have a genuinely fundamental difference in moral standards.

Normative relativism

The position that we should respect or at least tolerate people and cultures with moral standards that differ from our own.

Metaethical relativism is not the same as either of these positions, nor does it entail either of these positions. In fact, none of these positions entail the others. Unfortunately, critics of metaethical relativism often conflate these three positions.

References

Joyce, R. (2007). Moral objectivity and moral relativism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy archive. https://plato.stanford.edu/ARCHIVES/WIN2009/entries/moral-anti-realism/moral-subjectivism-versus-relativism.html

Pizarro, D. A., & Tannenbaum, D. (2012). Bringing character back: How the motivation to evaluate character influences judgments of moral blame. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), The social psychology of morality: Exploring the causes of good and evil (pp. 91–108). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13091-005

Need to read it again carefully and think it over, to see if I find anything to disagree with and how it maps to what I feel is my own stance. Haven't read metaethics yet (my approach to these topics has mostly come from evolution, game-theory and evolutionary psychology texts). I feel I have a very robust Moral antirealism, in which moral claims are rejected as saying anything about a stance-independent world. Beyond that, I am not sure if this would take to to affirming all ethical statements are false (that would be my initial inclination, in the sense of: assuming a correspondence theory of truth, there is no object of which moral claims of any type are a correspondence). I am not sure if I understood properly what stance-dependent moral facts would be. Is it something like: if you assume certain moral axioms (whether at the individual or the social level) some actions become 'true' or 'false' given those axioms and people that accept them? Like, I think i also accept a weak version of this, i.e., societies have evolved morality both biologically and culturally as a way of solving coordination problems, and if you accept some very minimal axioms you can perhaps build a contractarian view of morality as the set of freely agreed upon norms and rules that maximize individual and group flourishing and well-being.

According to appraiser relativism, what is it that Alex is expressing in the example you give? If, according to individual relativism, we index the statement "Stealing isn't wrong" to mean "[I am not opposed] to stealing," how can Alex be wrong, even if we are judging his views and actions according to the appraiser's standards? Is it just that the appraiser thinks Alex is wrong for not being opposed to stealing? Even in that case, since we've indexed Alex's statement to mean "[I am not opposed] to stealing," we can't say that he is genuinely wrong, only that our standards clash. I don't necessarily think this is a problem with the view, I am just trying to better understand appraiser relativism and how the view conceives of moral language.