A Critique of Nathan Nobis's Subjectivism Entry on 1000-Word Philosophy

1.0 Introduction

When I saw that 1000-Word Philosophy had a new entry on subjectivism I was looking forward to seeing how it was handled. I was disappointed. I am sympathetic to the desire of philosophers to disabuse students of superficial, disengaged, and often confused dependence on insisting just about anything is “subjective,” or “just an opinion.” I rarely agree with Bentham’s Bulldog about much, but overall he’s correct when he criticizes the alleged dichotomy between fact and opinion here.

Apparently, students are often taught this distinction in school. A mountain of similarly confused material can be found online. This is the first one I found, and, as you can see, it is embarrassing nonsense. For instance, the entry suggests the term “argues” in the phrase “The report argues that…” is a “signal word” for expressing an opinion, rather than a fact. This is bullshit. I’m not even going to bother to explain why. I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader, which I’m confident you completed before the end of this sentence.

The fact/opinion distinction is a bit of educational gobbledygook that serves to miseducate students. However, such impediments to productive reflection and class discussion shouldn’t be conflated with their more defensible counterparts in the form of philosophical positions defending subjectivism in various forms. I’m a moral antirealist, and my views are similar in many ways to moral subjectivists. Such positions aren’t merely the result of confusion, a desire to signal tolerance, or other poor reasons for endorsing a view.

This entry could have focused only on educating readers about misunderstandings about subjectivism or pointing out various ways students may use terminology in ways that don’t match the use of these terms among philosophers. For instance, Nobis suggests that people may declare a matter to be “subjective” when there is sufficient disagreement or when people are uncertain of what the answer is. This doesn’t just seem plausible to me, I have data that supports this. When I’ve studied how nonphilosophers explain their answers to questions about metaethics, many participants in my samples and the data I acquired from others suggests that they frequently conflate epistemic and metaphysical considerations.

However, most of the article is a tepid blend of loose speculation and thinly veiled disdain for subjectivism. I find this unfortunate, and it made me wonder: what was the point of this? I had thought that 1000-Word Philosophy was intended as an educational resource for students. On the About page of the website, it states:

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology is a constantly growing collection of over 200 original essays on important philosophical topics. These essays are introductions rather than argumentative articles. Each essay is as close to 1000 words (while never going over!) as the author can get it. A 1000-word essay takes between five and ten minutes to read. That’s about the length of a short bus ride or a waiting room stay, or the lead-up to a class meeting.

Entries come from a variety of authors, many of whom are presumably not affiliated with the website. But in this case, the lead editor, Nathan Nobis wrote the entry. The article appears to me to reflect the distinctive animus its author has towards subjectivism. Rather than serving as a relatively neutral introduction that could serve as a valuable resource for learning about subjectivism in its various forms (in this case, with respect to truth, ethics, and aesthetics), it instead reads as a condescending polemic engineered to discourage subjectivism. Worse, much of this is conveyed by unargued assertions of mainstream philosophical positions, without any indication that alternative views are represented by large and reputable minorities within the field. It also includes a worrying amount of speculative, noncommittal remarks about what people who express seemingly subjectivist views might think or mean, with such characterizations often leaning on the least defensible and most uncharitable possibilities. At other times, Nobis simply asserts that something is usually the case or makes bald declarations about what people believe with little supporting evidence. This would be fine if it were a blog entry. But this kind of entry doesn’t strike me as appropriate for 1000-Word Philosophy.

In short, the content of this entry conflicts with the stated aims of 1000-Word Philosophy. It is not an introductory article. It is an argumentative and highly partisan article that expresses the distinctive position of its author. No reasonable and well-informed philosopher could reasonably interpret this entry as neutral or as simply intended to introduce readers to the topic.

I hope most readers will reach the same conclusion if they read the article. My commentary is, perhaps, not needed. But I’ll go over some of the highlights to explain my perspective.

2.0 Truth subjectivism

The article begins well enough. It opens with “that’s subjective!” and goes on to question what people might mean by this. As someone who is constantly pushing concerns about insensitivity to polysemy and pragmatics, I was delighted to see Nathan begin by stating that while the term “subjective” indicates that “something important about the claim depends on the subject,” that “what this ‘something’ is varies depending on the claim.” Better yet, the first footnote notes:

There is no standard, set meaning of “subjective”: different people use the word in different ways: ask them!

So far so good. However, things get a bit odd as we move into the first section, which is on subjectivism about truth. Nathan proposes that one thing someone might mean if they say that truth is subjective is:

if someone believes some claim, then that claim is true: their believing it makes it true.

Nathan immediately remarks:

This can be called subjectivism about truth. It appears to be not true.

What on earth is “It appears to be not true” doing here? Why is Nathan telling us what he thinks, rather than simply telling us about what this view is? It would be one thing to say:

Critics argue that this appears to be not true…

…followed by the arguments or reasons that they have for objecting to the view. But Nathan doesn’t do that. Instead, he inserts himself into the article and simply declares that the position seems incorrect. Note, too, that “It appears to be not true” is the very first thing he says after describing the view. We’re given no elaboration of the view. No explanation of why someone might be drawn to the view, what arguments they might have for it, or anything even remotely approaching the faintest quantum of charitability, simply because we’re given nothing at all. The only thing we’re told about this view is that it “appears” to be “not true”.

Second, appears to who? I’ve criticized philosophers before for their lack of clarity and qualification when making such remarks, and I’ll keep doing so. See here for one example. Analytic philosophers sometimes exhibit the bad habit of saying things like this:

It seems plausible that…

It’s intuitive that…

It appears that…

…without specifying whether it seems plausible/intuitive/appears this way to them, or to competent, unbiased judgments, or to experts, or to most people, or to most well-informed people, or to most Geminis, or to most people born on August 11th, 1981. Sometimes, I worry that they are just presuming that claims themselves can be intrinsically intuitive, plausible, or to “appear” to be the case, as though there were an epistemic view from nowhere from which all claims could be judged as intuitive or counterintuitive, as “appearing” true or not, as though they’ve completely forgotten we all occupy a unique vantage point and see the world through our distinctive minds, minds which could be mistaken or confused in a variety of ways, such that just about anything could seem plausible or appear to be the case to someone.

Nathan does say a bit more following the remark that “It appears to be not true”:

It appears to be not true. Belief and truth are not the same: believing you’re a billionaire doesn’t mean you have a billion dollars; believing someone is imprisoned when they’re not doesn’t make that true.

Even if you were going to object to subjectivism about truth, this is a very weak response. First, Nathan states that belief and truth are not the same. This is irrelevant. Subjectivism about truth isn’t the view that belief and truth are the same. It’s the position that beliefs make things true. The position wouldn’t even make sense if it were the view that they were the same. For comparison, if someone held the view that “fire generates heat,” it would make little sense to point out that “fire is not the same as heat.”

Second, Nathan simply gives two concrete examples in which he asserts that the beliefs in question don’t make the claims in question true. An assertion to the contrary is not a substantive objection. Consider this exchange:

Theist: “God exists.”

Atheist: “No, God does not exist.”

Has the atheist shown that God does not exist? No. Likewise, Nathan has not shown that truth isn’t subjective merely by picking out a couple examples of things someone might believe and simply declaring that they’re not subjective. Granted, these examples are probably intended to serve as appeals to the reader’s intuitions. If so, this isn’t a great way to make such appeals. It isn’t explicitly attempting to court the reader’s judgment on the matter, but instead simply consists of a direct assertion to the contrary, as if that were a rebuttal to the view. Rather than asserting the contrary, this could have been framed more effectively as a question to the reader:

“If, when in a dream, you sincerely believe you are flying, does that mean that you are flying?”

Questions like these may be relatable to readers, and may prompt them to directly engage with subjectivism about truth and potentially judge it to be absurd on their own terms. This may have been what Nathan was going for. If it were, I think it could’ve been done better.

Next, Nathan appears to simply assert that the correspondence theory of truth is correct:

In general, beliefs and claims are true when they correspond to the facts of the world—the way the world is—and false when they don’t. This is the correspondence theory of truth.

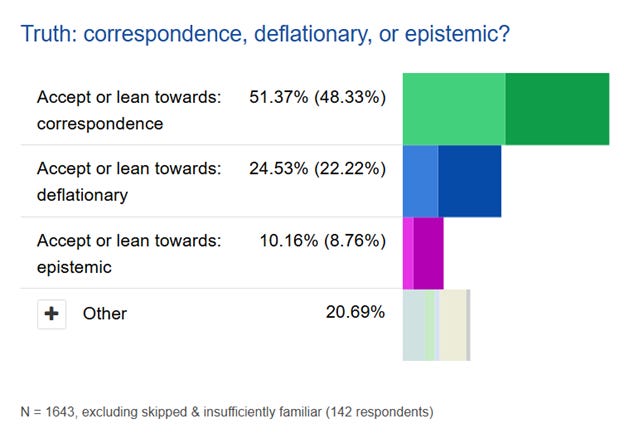

No arguments. No qualified claim that “many philosophers believe…” just a direct assertion of what is the case. This is an odd choice for pedagogical reasons. What makes it more odd is that only about half of the philosophers surveyed in the 2020 PhilPapers survey endorsed correspondence theory:

51.37% is an incredibly slim majority. It’s quite strange to present such a position as though it were some sort of established truth or consensus among philosophers. It isn’t.

Next, Nathan says:

When someone says something is “true to me” or “my truth,” they are usually just stating what they believe, which may be false or based on poor evidence—even if they feel confident or the issue is important to them.

Note the use of “they are usually just stating what they believe.” Regular readers will know what I have to say about this: that’s an empirical question. How does Nathan know what people usually mean? This doesn’t strike me as an absurd hypothesis. It might be true. But again, it’s simply asserted as if this were some sort of incontrovertible fact. I don’t know what exactly people tend to mean when they say that something is “true to me” or “my truth,” but it’s not at all clear they’re merely reporting what they believe. Such claims may carry implications about the speaker’s epistemic stance, or their values or attitudes towards the claims in question. For instance, when a person speaks of their truth, this may carry emotional overtones or signal a desire for others to acknowledge and respect their perspective on the matter. Reducing such remarks to merely a person asserting what they believe may fail to capture the full content of what the person is expressing.

Nathan adds in a footnote accompanying this remark that:

Sometimes people call beliefs “subjective truths.” But since beliefs need not be true—they are sometimes false—calling beliefs “truths” is confusing: that allows for the possibility of “false truths.” So the phrase “subjective truth” is likely best avoided. Some truths, however, are called “objective” truths, but since “non-objective truth” or “subjective truth” doesn’t make sense—at best, that’s just belief—“objective” truth is better just called truth.

Again, Nathan simply appears to be asserting the contrary. The entire footnote simply serves to tell the reader that the position is wrong and does so in a flagrantly presumptuous way. Note how Nathan states that “subjective truth” doesn’t make sense: well, whether it makes sense or not is precisely the matter of contention a proponent of subjectivism about truth would dispute. If it’s a crude, flat-footed subjectivism, I’d probably agree with Nathan that such views aren’t correct. But should this article really take up so much space to repeat over and over that this view is wrong, rather than simply tell the reader more about the view? I thought the purpose of 1000-Word Philosophy was to provide an introductory perspective on various topics in philosophy, not a pulpit to lecture readers on what they or others are wrong about.

Nathan moves to state that:

A “that’s subjective!” reaction might also be based on someone thinking something like this:

there is not strong evidence for that belief; it is not knowledge; it is not something that everyone must accept or agree with.

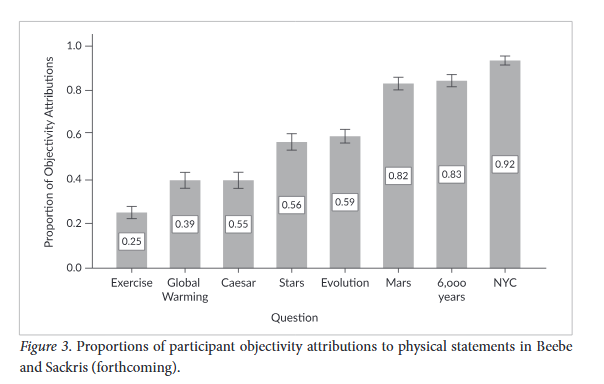

This is appropriately qualified with the phrase “might also be based on…” and, as it happens, I have empirical data on how people describe their metaethical views. Quite a few do appear to make remarks indicating an epistemic stance, even when this isn’t technically what they were being asked. In other words, when asked in various ways about their metaphysical stance on morality, people may favor antirealist response options not because they clearly appear to believe there are no stance-independent moral facts, but because they think the matter is controversial, difficult to resolve, or uncertain. This is even more evident when we look at Beebe’s (2015) studies involving disagreements about various scientific claims. Beebe asked the following:

“If someone disagrees with you about whether [statement] is true, is it possible for both of you to be correct or must one of you be mistaken?”

Here is a list of the statements Beebe used:

Frequent exercise usually helps people to lose weight.

Global warming is due primarily to human activity (for example, the burning of fossil fuels).

Julius Caesar did not drink wine on his 21st birthday.

There is an even number of stars in the universe.

Humans evolved from more primitive primate species.

Mars is the smallest planet in the solar system.

The earth is only 6,000 years old.

New York City is further north than Los Angeles.

If you had to categorize these items in terms of how much of a consensus there is, how would you do so? I think these would go in roughly ascending order, with 1-4 being the lowest consensus (that is, the highest amount of disagreement) and the last 5-8 having the highest consensus. And what would you predict as far as people’s tendency to judge that if someone disagrees, that you could both be correct? If you’re thinking that this number should be higher for items for which we’re uncertain or are a matter of controversy, give yourself a gold star, because that’s exactly what Beebe found:

A good explanation for these findings is that people are interpreting a question ostensibly intended to be about whether truth is subjective or not as a question about our epistemic positions. If so, such findings would support Nathan’s claims. I want to stress, then, that I don’t have a problem with Nathan making empirical claims. My concern is with making such claims in the absence of supporting empirical data.

However, I also want to highlight something odd about Nathan’s article. Nathan keeps vacillating between criticisms of subjectivism, and claims about various things people might mean when claiming that truth is subjective that don’t match the philosophical position of subjectivism about truth. Sure, it may very well be that people who claim that something is “subjective” are sometimes making epistemic claims. In which case, they’re not subjectivists in the sense of thinking truth is determined by belief. This is not any sort of objection to subjectivism about truth, though. Nathan doesn’t draw out this distinction clearly enough and moves from discussing various things people might mean and critiquing a standard characterization of a philosophical position that answers to terms like “subjectivism.”

Nathan’s last remark on subjectivism about truth is also interesting:

A challenge though: a “that’s subjective” reaction might itself be “subjective,” if it is based not on a strong understanding of the issues and arguments. Maybe people sometimes react “that’s subjective!” to avoid the work needed to get that understanding.

Maybe they do. Note how such speculation, sprinkled throughout the article, tends to cast subjectivism or anyone who says things like “that’s subjective!” in a negative light, identifying questionable motives on their part, such as in this case an implied intellectual laziness. Sure, people who say these things could be lazy. But how does speculating on the possible motivations of people who make such remarks, with no evidence at all to support such a contention, advance a reader’s understanding of subjectivism? I don’t think that it does. Instead, this strikes me as an indirect way of disparaging people who express such views. For comparison, imagine if I were writing a short entry on moral realism and included the remark:

“Maybe people sometimes endorse moral realism because they want to avoid the work of having to determine their own values and find meaning and purpose in their lives on their own.”

This would reflect a legitimate existentialist stance a philosopher might take on the matter, and it might even be true, but is it suitable for an introductory article? Should introductory articles take digs at people whose views the author doesn’t like? Would this really be an ideal remark to include in a very short essay, when the author could have instead provided more information about the view rather than speculating on the vices of those who endorse it?

3.0 Ethical Subjectivism

Nathan moves on to ethics next, where we’re told that it’s common to say that ethics is subjective. Fair enough. Yet Nathan proceeds to characterize subjectivism exclusively in agent relativistic terms:

What might people who say this be thinking here? Perhaps this:

if someone disapproves of doing an action, it’s wrong for them to do it;

if someone approves of doing an action, it’s right for them to do it

It’s true that this is one position people might be referring to. But they might also be referring to the view that whether an action is right or wrong can only be judged relative to our respective moral frameworks, in which case one might endorse something like individual appraiser relativism. I’ve criticized Nathan for being insensitive to this distinction already in this article. Here is the distinction:

According to agent relativism, moral claims are true or false relative to the standards of the agent performing the action (or that agent’s culture, etc.).

According to appraiser relativism, moral claims are true or false relative to the standards of whoever is evaluating the action in question (or the standards of the appraiser’s culture), even if they are not, themselves, performing the action.

While the former is a legitimate form of relativism and may reflect what someone means if they say that morality is subjective, this position is also highly vulnerable to a particular line of objection: that would entail that the agent relativist/subjectivist would be obligated to agree that, if someone thinks torture or genocide is morally acceptable, then it is morally acceptable for that person to commit torture or genocide. This is, naturally, supposed to prompt audiences to balk and realize how horrifying and evil “subjectivism” or “relativism” is. If one does not draw out the distinction between agent and appraiser varieties, one might be given the misleading impression that subjectivism/relativism have been refuted full stop, rather than there being an objection to at best only one form of the position. It is curious that Nathan opts exclusively to focus on agent relativism, given how vulnerable it is to an easy objection, but not its appraiser counterpart. However, the remark that most caught my attention in the entire article comes next:

Although people sometimes talk like they accept ethical subjectivism, it’s unlikely that anyone really accepts it.

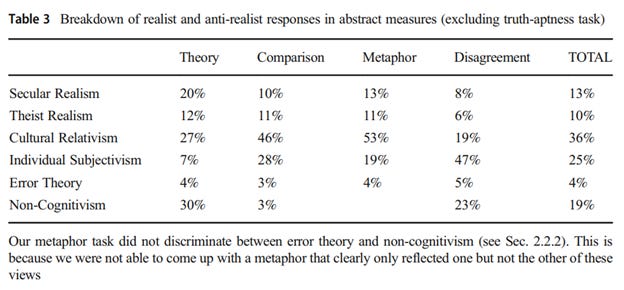

Whether anyone really accepts a metaethical position is an empirical question. Consider the results of Pölzler and Wright’s (2020) groundbreaking study that didn’t simply assess whether participants were moral realists or antirealists. Instead, they developed seven different paradigms and evaluated which specific metaethical stances people favored. These paradigms were intended to correct for the methodological shortcomings of earlier studies and were probably at least partially successful. What did they find?

…They found that cultural relativism and individual subjectivism were quite popular, with individual subjectivism coming in second place at 25% of the total sample. Now, I’ll be the first to say that this study has methodological limitations. The samples were drawn from populations that were disproportionately young and more likely to be atheist/agnostic, so their results are probably not representative of most of the world’s population. More importantly, there are significant methodological challenges to any studies on metaethics. I should know: my entire dissertation centered on these shortcomings.

You might also worry that “Individual Subjectivism” in this study doesn’t comport with Nathan’s description of the view. Well, let’s have a look at how it was characterized in their study (the other three tasks didn’t include a subjectivist option or it was redundant with previous response options):

Theory task

When a person says that something is morally right or wrong, good or bad, etc. she intends to state a fact. Such facts exist – and they depend on what individuals think about them. For example, an action is only morally wrong if you yourself believe that it is morally wrong. If you did not believe the action to be wrong, it would not be wrong.

Metaphor task

Moral facts are “individual inventions”. They are introduced and determined by individuals.

Comparison task

Morality is akin to personal taste or preferences. For each person different things can be morally right or wrong. The individual determines the moral facts.

Disagreement task

(Participants are asked whether two people who disagree about a moral issue can both be correct)

Both people are right (because the truth of moral sentences is determined by the moral beliefs of individuals).

Every single one of these measures appears consistent with agent individual relativism (i.e., how Nathan characterizes ethical subjectivism) and in some cases is an even better fit than it would be for appraiser relativism. Yet in spite of this, a considerable number of participants selected this response option. Does this mean these people are ethical subjectivists in the sense Nathan describes? No, it does not. Figuring out what (if any) metaethical position people hold is difficult. But that’s just it: it’s so difficult that we shouldn’t even trust the results of seemingly straightforward studies. What we certainly shouldn’t trust is our personal armchair reasoning about what it’s plausible for nonphilosophers to believe. And yet that’s all Nathan has. Even a study with shortcomings is better than that. See what Nathan has to say about why it’s unlikely anyone endorses ethical subjectivism:

First, it seems to imply that, e.g., if someone approved of assaulting innocent people for fun, then it’d be not wrong for them to assault people. But almost nobody agrees with that.

Yes. It does imply that. So how does it follow that it’s unlikely anyone accepts such a view? We’re not told. Presumably, this is such an outrageous implication that nobody could believe it. There are people who think the world is 6,000 years old. Quite a lot of them. People believe all sorts of things. What’s so remarkable about people having beliefs that Nathan (and, as it happens, myself) would regard as outrageous? Nathan doesn’t have any empirical evidence that “almost nobody agrees with that.” Pölzler and Wright do. One might be tempted to wonder whether these participants would sustain their support for subjectivism if this implication were made explicit. I suspect most wouldn’t. So Nathan may very well be right here. But the issue is that this is still an empirical question, and rather than consult any data at all, Nathan just makes a declaration about human psychology.

Now, at this point, one might wonder: well, if you ultimately agree people probably wouldn’t accept this implication of subjectivism, so why are you giving Nathan such a hard time? The issue is twofold: First, one should consult empirical data when it’s available for addressing empirical questions. Philosophers are far too quick to rely on what they think is plausible. They’ll often be right, but when it comes to empirical questions about human psychology, except in the most inane of cases (e.g., most people probably don’t want to be set on fire), caution is warranted. But the other issue is that if it really is so unlikely that most people would endorse this form of subjectivism, maybe this should prompt Nathan or other critics of “subjectivism” to wonder whether their target is too narrow. What about individual appraiser relativism? Maybe people have that in mind. Yet Nathan does not explore this possibility.

I also worry about the kinds of examples Nathan uses. Consider this one:

Second, suppose we learned that some school shooters sincerely believed they did nothing wrong: almost nobody would think that means they actually did nothing wrong.

While it may seem plausible that people would relent in this case and insist that a school shooting was “actually” wrong, there is a worry that normative entanglement could be in play here. People worry about what their remarks may signal about their attitude and character. Even if they are against the worst things human beings could do, and would never do so themselves, they might be unwilling to respond in the affirmative to cases like this, since it could signal false or misleading information about their character. I refer to this as normative entanglement, and have written about it previously. With respect to this form of subjectivism, however, Nathan wouldn’t be entirely wrong to maintain that the undesirability does stick, and that this is a shortcoming of the view. What he describes as ethical subjectivism and what I prefer to refer to as individual agent relativism is a pretty deplorable view. Ironically, however, I find it deplorable mostly due to how similar it is to moral realism.

How is it similar? If you’re an agent relativist, and someone else thinks it’s okay to torture babies, it is in fact okay for them to torture babies, and it would be wrong for you to intervene. It’s not easy to get around this implication. Even if you think it’s morally obligatory to stop anyone from torturing babies, now you have a serious internal tension in your account. Maybe it can be resolved. I don’t know. I haven’t tried to thread that needle. Ironically, however, what makes it so deplorable is that if you were obligated to stand aside while someone else tortured babies, you wouldn’t be obligated in virtue of your subjective values or moral standards, but in virtue of theirs. Their moral values thus serve as an outside imposition on you, constraining what you can and can’t do in ways independent of your own values. It doesn’t matter how much you’re against baby torture if they’re for it. This is much like moral realism, in that it likewise obligates you to act in certain ways independent of your own goals and values. Appraiser relativism isn’t like this, however, and doesn’t suffer from the shortcomings of agent relativism. So why doesn’t Nathan consider this possibility? I don’t know. Maybe he’ll respond to this post and let us know.

There is more to the tepid critiques of “subjectivism” than the agent/appraiser distinction. While “subjectivism” in a crude and simplistic form may be vulnerable to various objections, the same could be said of many other philosophical positions. Yet in most of these cases, proponents of these views take it upon themselves to flesh out the views, building on their earlier foundations to refine, and sometimes alter the view in significant ways. In a recent post decrying the poor quality of objections to subjectivism, Travis notes, for instance:

On a simple version of this view, “X is wrong” would translate to “I disapprove of X”, however there are other variations as well. On some subjectivist views, moral statements may instead refer to what attitudes you would have if you met some specified condition (like knowing all the relevant non-moral facts) or specifically about your higher-order attitudes.

Note that this initial characterization: that “X is wrong” = “I disapprove of X” fits better with appraiser than agent relativism, and it isn’t subject to the critique Nathan presents. Again, part of the issue with agent relativism is its weirdly realist-like qualities. If you’re an agent relativist, you think something like this:

Alex: “I think torture is wrong” = this makes it wrong for Alex to torture.

Sam: “I think torture is morally required of me” = this makes it morally required for Sam to torture.

Each person generates and self-legislates a body of moral facts uniquely for themselves (there are caveats: what if you think you have a right to stop anyone from torturing? Nathan does mention this, and does raise some legitimate concerns with the internal conflicts this can generate, so credit where it’s due). The issue is that one’s beliefs or attitudes somehow “create” moral facts that are then binding in such a way that everyone else has an obligation acknowledge and abide by those moral facts. So if a person thinks it’s okay to steal, you must be okay with them stealing. Your own attitudes about their actions are removed from the equation and are metaethically irrelevant: they legislate the rules for themselves. I’ve jokingly called this à la carte realism, not because it is a form of realism (it isn’t; moral facts are stance-dependent on this view), but because its functionally similar to realism in that it creates obligations that are binding on others independent of their own goals and values.

Appraiser relativism simply doesn’t have this problem. I act based on my values. You act based on yours. I judge your and my actions based on my values. You judge your and my actions based on yours. Appraiser relativism never requires you to think that any person or culture’s actions are justified merely because they think they are, because you judge those people or cultures by your standards (or the standards of your culture).

Appraiser relativism can circumvent some common problems with agent relativism, but so too can Travis’s other suggestion, that “moral statements may instead refer to what attitudes you would have if you met some specified condition (like knowing all the relevant non-moral facts) or specifically about your higher-order attitudes.” A critic may say: “That’s not subjectivism! That’s Humean constructivism!” …or something along those lines. This would be a matter of terminological squabbling. It wouldn’t make any sense to reject the entire expressivist project in metaethics on the grounds that Ayer’s emotivism is terminally flawed. Likewise, it would make no sense to insist there are no ways to elaborate on or develop accounts of morality that have their origins in something akin to subjectivism, even if they move away from it. Perhaps the “intuitive” subjectivist is a kind of inchoate constructivist of some kind. Philosophers seem entirely comfortable attributing a host of implausibly sophisticated realist views to people, so why downplay the possibility of similarly sophisticated skeptical or antirealist views? There is a double standard here, and it is an unflattering one: critics of antirealist views like subjectivism routinely target the view in its crudest forms, often focusing on:

Misunderstandings and errors among laypeople and college undergraduates, rather than focusing on the more sophisticated forms of these views

Crude, primitive forms of the positions in question, often with no discussion of different and more developed forms of the view

Often stop at an initial round of rebuttals, with no acknowledgement that proponents of the views in question have responses to the initial rebuttals (ones that I personally think are often quite good)

These behaviors are consistent with a kind of intellectual negligence. People who critique views in accord with (1)-(3) likely don’t apply the same standards of rigor and seriousness when addressing these positions as they do other positions, and if I may indulge in a bit of armchair speculation about why: I think it’s because they personally dislike these views. It makes their job harder. It makes the task of getting on with normative theorizing more challenging. It rubs up against their own intuitions and inclinations. One recent commenter, Glen Kappel, echoed these sentiments on another article, stating:

I’ve come to think that what is going on here is that antirealism (of any kind) is considered anti-philosophical by people who teach philosophy in general. To be an antirealist is, in their minds, to betray the project of philosophy as they understand it. Philosophy *just is*, on this metaphilosophical view, the attempt to reach or arrive at timeless universal truths about the way things are from a Gods-eye View from Nowhere. If you are not seeking such conceptions of Truth or objective facts pertaining to each domain, why even do philosophy? This seems to be the prevailing attitude.

So the field itself selects for people with strong inclinations toward moral realism, both in terms of profs and students. Self-selection effects follow in both directions. Ethics profs see themselves as courageous defenders of the idea that there are context-free true moral statements or objective moral facts. They are standing up for truth-seeking—that’s the duty of philosophy (as they see it)! Conversely, if you don’t think morality is real or that there are universally normative moral facts, you may not bother taking any Ethics classes let alone consider becoming a prof teaching the field. Pragmatic antirealists, I suspect, are more likely to leave academia (or analytic philosophy) than realists; partly due to feeling unwelcome, partly due to lack of interest or preferring to do something more practical with their lives.

I don’t have any data to support this claim, but I am sympathetic to it as a working hypothesis I’d bet on. In case you’re worried that I’m psychologizing the opposition in the absence of evidence, well, I can give you at least some evidence. Another commenter, Mya Jo, noted that Huemer explicitly expresses a hatred of truth relativism in his book Knowledge, Reality, and Value in chapter 5, section 5.6, helpfully titled “I Hate Relativism and You Should Too”:

Truth relativism does not just fail to be true, and it does not just fail to aim at truth; truth relativism actively discourages the pursuit of truth. How so? The relativist essentially holds that all beliefs are equally good. But if that’s the case, then there is no point to engaging in philosophical reasoning. We might as well just believe whatever we want, since our beliefs will be just as good either way. But this undermines essentially everything that we’re trying to do.

It does not undermine everything I’m trying to do. Even if a relativist thought all belief was “equally good,” that would not bar them from engaging in intersubjective, shared, practical enterprises with others. For instance, are there any stance-independent facts about which games are best? Magic: The Gathering, Call of Duty, chess, and so on? I don’t think that there are. Does this make any pursuit of advancing, understanding, or engaging with these games pointless? Not at all. The whole point of pursuing these games is because doing so satisfies our goals or desires. Why is it not a legitimate perspective to suppose that this generalizes in some fashion, and that our own subjective values are fundamental to the entire philosophical enterprise, without this bringing the whole enterprise crashing down? Even if we are all the ultimate locus of value for ourselves, our values overlap, and in those shared values we can identify and engage in shared pursuits. Even if truth were in certain critical ways dependent on our goals and values, this would not necessarily bar us from engaging in productive pursuits, including philosophical pursuits.

I’m not a relativist about truth, but I am a pragmatist. I reject outright any notion of a “view from nowhere” or a reality with a nature wholly disconnected from our lives and pursuits as embodied agents. There is an ineliminable, inescapable, perspectival aspect of the pragmatist’s conception of truth, one that does, in practice, allow to a limited extent for a claim to be true relative to different individuals. Classical pragmatists hold, roughly, that truth is what “works,” and what works for each of us can differ. This can be highly misleading, as it might give one the impression that anyone can believe anything and that their believing makes it so. Pragmatists don’t think this way. They’re not crude relativists. But on the pragmatic view of truth, truth does require a perspective from which to adjudicate incoming information, such that truth is the end result of a process of corroboration, verification, and ultimately integration with the rest of one’s beliefs. This process does ineliminably involve us in the equation. There is no view from nowhere. There is no ghostly, disconnected perspective from which all truth could be adjudicated in some way independent of our perspectives on the matter.

Am I going to insist that pragmatism allows fully allows for us to achieve Huemer’s aspirations? After all, note that Huemer hates relativism about truth because it:

[…] undermines essentially everything that we’re trying to do.

No. I’m not. I do think such views undermine at the very least a lot of what Huemer and others are trying to do. And the same holds for pragmatism. Consider the infamous squirrel example from William James.

A man is chasing a squirrel that is on a tree. The squirrel always remains opposite the man as it clings to the trunk. Is the man going around the squirrel? Pragmatism is in part a method for dissolving pointless metaphysical disputes like this. We can break down the question as:

Is the man moving north, east, south, west, and so on as he moves with respect to the tree? Yes. In that case, he is going around the squirrel.

Is the man passing around the front, sides, and back of the squirrel? No, because the squirrel always remains facing the man. No. In that case, he is not going around the squirrel.

Now, you don’t need pragmatism to dissolve this sort of question. But examples like these provide, in a presumably humorous and simple form, the manner in which allegedly serious and credible philosophical disputes may be pseudoproblems that result from insufficient clarity and/or (there should be a word for and/or) a lack of concern with the practical differences between different potential construals of the circumstances. This example illustrates how a budding philosophical problem may be no genuine problem at all. Just so, the pragmatic method may allow us to dispense with much of what passes for serious academic philosophy. Sure enough, I believe the field is rife with pseudoproblems and that philosophers often occupy themselves with pointless squabbles over inane matters, and use bad methods to do so.

So, while I don’t think pragmatism undermines everything Huemer and others are trying to do, I think it undermines quite a lot. But, as a critic of Huemer’s methods and metaphilosophy, I am in favor of this. Huemer’s hatred makes sense. Views like relativism and those that have some affinity with it are a threat, at the very least, to Huemer’s (and those with similar metaphilosophical outlooks’) entire approach to philosophy. It does threaten what they do on a fundamental level. This seems, then, to provide at least some reason to worry that Huemer and others may be biased and even hostile. This is not even entirely a matter of speculation; Huemer literally titled the section “I Hate Relativism and You Should Too”. It doesn’t get much more on the nose than that. Does Nathan hate subjectivism? If not, is there at least some disdain? If Nathan shares similar sentiments as Huemer, should Nathan be the one to write an article on the topic?

Nathan continues to make claims of questionable suitability to a site ostensibly intended to introduce people to philosophical topics. Next, he says:

Someone might say an action isn’t wrong “to me”—meaning they believe it isn’t wrong—but that doesn’t seem to mean it’s actually not wrong: beliefs about ethical matters can be mistaken, just like other beliefs can. Ethical subjectivism denies that and so seems to be false.

There are a few problems here. First, what does Nathan mean when he says that it doesn’t seem to mean that it’s “actually” not wrong? What does “actually” mean here? If “actually” means “in the realist sense,” then this is both (a) misleading and unclear and (b) worse, seems to presumptuously help itself to the question-begging assumption that the only “actual” sense in which anything is wrong is in some non-subjective sense. But subjectivists have no reason to agree with this. Subjectivism offers its own account of moral truth. If subjectivism were true, and realism were not, then the only sense in which anything is “actually” wrong would be in the subjectivist sense. I have previously written about other instances in which philosophers make misleading and inappropriate use of terms like “actually,” “really,” “genuinely” and so on here.

Nathan’s remarks here show an incautious slippage into the presumption of the truth of his own perspective when writing, a perspective fundamentally at odds with the position he’s trying to introduce readers to. This simply isn’t appropriate for an educational article. For comparison, a neutral article describing Christianity should not include phrases like:

While many people doubt the resurrection of Christ, what actually happened that day cannot seriously be questioned. Jesus rose from the dead.

Nathan’s remarks are quite similar to this. Immediately following the claim that this doesn’t seem (again, seem to who?) to mean it’s “actually” wrong, Nathan simply asserts that “beliefs about ethical matters can be mistaken, just like other beliefs can.”

Well, that’s one perspective, and the subjectivist might disagree. Again, Nathan doesn’t say anything like “Critics would insist that beliefs about ethical matters can be mistaken.” No, he just asserts that they can be from his own authorial perspective. But the final remark is especially strange:

Ethical subjectivism denies that and so seems to be false.

Ethical subjectivism denies that our ethical beliefs can be mistaken? Well, first, it’s not clear that it does. Consider the story Green Eggs and Ham by Dr. Seuss. In the story, Sam-I-Am approaches a man and offers him green eggs and ham.

The man insists he does not want to try it because he does not like green eggs and ham. The story proceeds with Sam-I-am pestering the man until he relents and tries the green eggs and ham. It turns out that he likes them. He was mistaken about his own preferences.

This is a story we read to children. Children are often fussy eaters, insisting they don’t like this or that food. But often they refuse to try it. If they do try it, sometimes they like it. Sometimes they are wrong about their own preferences. I want to stress something important about this story:

We teach children that you can be wrong about your preferences. Why would a philosopher be comfortable simply declaring that subjectivism entails that you cannot be mistaken about your ethical beliefs? No, this is not an implication of subjectivism. It would only be an implication of both subjectivism and the belief that we have infallible knowledge of our desires or values (or whatever it is that determines moral truth for the subjectivist). Subjectivists aren’t obligated to endorse such infallibility, so it simply isn’t an entailment of the view. This is what I am talking about when I criticize Nathan: there simply isn’t enough effort put into grappling with what a subjectivist might actually say in response to the objections and, if we’re being honest, simply bald assertions to the contrary that Nathan keeps making throughout this article. Nathan isn’t offering us rebuttals. He’s offering a simplistic caricature of a view coupled with declarations that the view is wrong, with no accompanying arguments.

Not only is this not appropriate for the intended purpose of the site, but the whole tone of the article is also antithetical to what ought to be the pedagogical aims of anyone concerned with teaching students philosophy. A good introduction to philosophy should itself exemplify good philosophy. It should be critical, cautious, skeptical, and present positions with either qualifications or supporting arguments. Nathan’s article exhibits none of these qualities. It is an impatient, dogmatic, finger-wagging, and repetitive lecture almost devoid of critical engagement with the view its “introducing” readers to.

The problems with this single sentence don’t even end here. Let’s return to the sentence:

Ethical subjectivism denies that and so seems to be false.

Although subjectivism allegedly denies that ethical beliefs can be mistaken, we’re told they can be mistaken, so it “seems false.”

Seems false TO WHO? I feel like I’m becoming an owl at this point. I am compelled to keep saying who, who, who:

Since when did it become appropriate to make the intellectual move that something “seems” not to be the case? Actually, it’s probably been this way for a while, at least among philosophers. But it really shouldn’t be. Whether something “seems” a certain way to someone will vary from one person to another. Things may “seem” a certain way to Nathan, but Nathan shouldn’t presume to speak on behalf of his readers, or everyone, or whoever he might be referring to when he says that things seem a particular way. It’s incredible that I have to say this, but things seem different to different people.

Nothing about subjectivism “seems” false to me. It seems to me that Nathan and many other philosophers assume, without adequate justification, that the way things seem to them is the way they seem to all or most other people (or at least all or most other right-thinking people). If this is what Nathan means, then it is a mistake, and twenty years of experimental philosophy should’ve been enough to motivate caution among philosophers. But it’s not clear what Nathan (or others who say similar things) mean, because they’re not clear. That’s odd, because analytic philosophy is supposed to pride itself on clarity. Yet time and again, you’ll see analytic philosophers make unclear and ambiguous remarks. It should be a red flag when they do. I suspect analytic philosophers often paper over the shortcomings in the field’s methods when they resort to vague or ambiguous remarks.

Next, Nathan makes a straightforward error. He says:

If ethics (not beliefs about ethics) isn’t “subjective,” then it would be “objective”:

This is not true. One could, for instance, be a noncognitivist. Noncognitivism holds that moral claims are neither true nor false, but instead only express nonpropositional content, such as emotions (“Boo abortion!”) or prescriptions (“Don’t get an abortion!”). Noncognitivists reject subjectivism as described here, but they also reject the claim that morality is objective. Likewise, ideal observer theorists and some constructivists believe moral facts do depend on stances in one way or another, but are not straightforwardly subjectivists. And, of course, “subjectivism” includes other views that Nathan didn’t discuss (such as appraiser relativism). Nathan’s remarks can readily give the impression that if one rejects this one specific form of subjectivism, that the only alternative is objectivism, and not other forms of subjectivism, or other views which treat moral facts as stance-dependent. I understand the need for simplification in introductory articles, but simplification should not come at the cost of inaccuracy. Next, Nathan says:

Sometimes it’s difficult to figure out what’s ethical: careful fact-finding and reasoning are required: e.g., we can’t know whether a war is ethically justified without knowing about its causes and how it’s being conducted. Ethical subjectivism, however, implies that ethical questions are always easy: just check your own feelings to find what you approve of.

This is also extremely objectionable. Nathan simply presumes that, if you’re a subjectivist, it’s easy to figure out what’s morally right or wrong: you just “check your own feelings.” Consider the following decisions, all of which depend, fundamentally, on our own subjective goals, values, and desires:

What profession to pursue

Who to marry

Whether to have children

Whether to go to a party tonight when you have work in the morning

Where to go for dinner

What your favorite movie is

What the best work of art is

Sometimes these questions are easy for people. Often, they are not. For each of these questions, our own goals and desires are in the driver’s seat. But even as a subjectivist, where your judgments about what’s good, bad, right, wrong, and so forth bottom out in your personal values, this does not necessarily make figuring out what’s morally right or wrong easy. Why? A few reasons.

First, our moral values, just like our prudential, aesthetic, and other normative and evaluative concerns, are often deeply embedded in and contingent on a host of non-evaluative/normative considerations that we may be uncertain about and may be matters of contention. Should you marry that particular person? Well, it depends on your assessment of their character and their goals. Are they trustworthy? Reliable? Committed? There are non-evaluative facts about these questions that you may not have the answers to. Even for a question as simple as deciding what to eat, one might find themselves conflicted, or uncertain. Travis makes a similar remark in his response to David Enoch:

Of course stance-independent facts are relevant to my evaluation of the permissibility of abortion - at what point the fetus develops the ability to feel pain, how painful abortion would be for a sentient fetus, etc. are all morally relevant considerations - but ultimately the moral status of abortion is a question about my values.

What kind of beings do I care about? How do I prioritize the bodily autonomy of the mother vs. the life of the fetus? These are the kinds of questions that I think determine whether abortion is permissible or not.

Second, we sometimes don’t know what our own preferences or values are. As Travis points out in this excellent defense of subjectivism:

Sometimes what exactly […] our values are or what would be conducive to achieving our goals is opaque to us. Thus it makes sense to engage in moral deliberation - even if you believe morality is subjective.

By sheer coincidence, this article was published the same day I wrote this (July 30th, 2025). And yet what Travis goes on to say is exactly on point:

Just because the answer to a question is subjective doesn’t mean it’s immediately obvious. Lots of people are mistaken about what they value - just look at the number of people that defend the permissibility of meat eating by appealing to the fact that animals have lower cognitive capacities than us. Obviously this isn’t an accurate reflection of what these people value - if it was, they would also be okay with farming humans with equivalent cognitive capacities to farmed animals for food. But they’re not.

Travis even adds another relevant remark. Realists will sometimes suggest that on their view, we “discover” the moral facts while many antirealists and especially subjectivists just “invent” or “make up” their values. Yet as Travis notes:

By the way, I find the insistence that the realist view is that we “discover” the answer to moral questions, whereas the subjectivist view is that we “invent” the answer very strange. I wouldn’t say that I “invent” the fact that pesto pasta is tasty. If anything, it sounds way more natural to say I “discovered” it.

Likewise with moral judgments. It sounds way more natural to say that I discovered that eating meat is out of accord with my values then that I invented that it’s out of accord with my values!

Subjectivism does not entail that moral questions have easy solutions. Moral considerations are entangled in many nonmoral considerations that we may be uncertain of. For instance, suppose that you’re a subjectivist and a utilitarian: Your subjective moral stance is that we should maximize happiness and minimize suffering. While it is easy to provide an abstract answer to any given moral question: “do whatever maximizes happiness and minimizes suffering,” this does not mean that you actually will know what to do in practice, since what will, in fact, maximize happiness and minimize suffering is often anything but obvious.

Once again, Nathan offers a superficial and one-sided criticism of subjectivism that fails to appreciate how a subjectivist might respond.

4.0 Conclusion

I’ll skip over the section on aesthetics and move on to Nathan’s final remark:

Here we tried to better understand some common “subjectivisms.” Are any of the insights we gained “just subjective”? No. At least, hopefully not.

Note the use of “just” in “just subjective.” This is a misleading modifier. It gives the impression that if something is subjective it’s “just” (or one might say “only” or “merely”) subjective, which implies that if something is subjective it is somehow less, or worse, or inferior to something being non-subjective. Second, note the very last remark: “No. At least, hopefully not.” Nathan ends with a remark that strongly indicates that he thinks it’d be a bad thing if our insights were subjective, as indicated by hopefully not. I fail to see how any student trying to learn about the topic would benefit from learning that Nathan hopes any given position or insight we have isn’t subjective. His personal distaste for a view simply isn’t something likely to contribute to anyone’s understanding of a topic and is yet another indicator that this entry serves more as a personal pulpit for Nathan to disparage subjectivism. Perhaps a more important question isn’t whether any insights we gained from this article are “just subjective,” but whether we gained any insight at all. I suspect not.

I doubt Nathan will care about my subjective stance on the matter, but I’ll offer it anyway. Articles like this one should’ve been written by someone with less contempt for the subject matter. Nathan easily could have reached out to someone who was more sympathetic to the view in question and invited them to write the article. But he didn’t do that. I think that was a poor choice and I hope Nathan will reconsider the inclusion of this article on 1000-Word Philosophy.

References

Beebe, J. (2015). The empirical study of folk metaethics. Etyka, 50, 11-28.

Pölzler, T., & Wright, J. C. (2020). Anti-realist pluralism: A new approach to folk metaethics. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 11(1), 53-82.

When making an argument against moral anti-realism, you most often hear some kind of 'but doesn't that mean you think (x hyperbolic example) isn't wrong!?', but this has transferred the question from 'are morals mind-independently real', to 'does moral belief drive action', an entirely different question. The implication is that the person is more likely to do those things, and it amounts to a barely transparent accusation, as we expected from the apostles of 'charity'. If this implication isn't intended, then that response amounts to 'How can you think realism is wrong? That would mean you think realism is wrong!', a simple tautology. You've spoken at length about how 'isn't wrong' is entirely conflated with 'isn't mind-independently wrong' here.

People do not make 'moral decisions' on the basis of abstract judgments about types of actions, but about actual concrete situations in the world. And this explains why among the same people who say 'but you can't be serious about saying genocide isn't wrong', probably also can be found those supporting actual genocide as in Palestine or more likely just not caring, as in South Sudan. I suspect the popularity of moral realism amongst anglophone analytics has got to do with the fact that it is actually easier to justify anything and everything on its basis than it is with anti-realism.

Have you discussed the pragmatic view of truth in more detail elsewhere?