Bentham's Blunder (Full post)

A response to "Moral realism is true"

1.0 Introduction

I’ve been working on a response to Bentham’s Bulldog’s (hereafter “BB”) blog, “Moral realism is true” for a while. That response ended up approaching the length of a short book, so I’ve opted to write a slightly shorter critique. It’s still very long, but I wanted to get it out there anyway. In a way, it’s a kind of retrospective of various points I’ve raised about the dispute between moral realists and antirealists in the past two years on this blog. As you’ll see, I frequently refer to earlier posts that address specific points.

In brief: BB presents an aggressive polemic in favor of moral realism, but fails to present any good arguments for moral realism. My “short” response will still be pretty long. I don’t think it’d be worthwhile to revisit the longer version. We’ll see.

Much of this outline is a point-by-point of the order of commentary as it appears in BB’s post. That will probably not make for very exciting reading. I would strongly encourage reading or referencing the article before reading this or referencing it as I proceed.

2.0 Response to “An Introduction to moral realism”

BB’s introduction consists almost entirely of empty rhetoric and dubious claims that seem intended to depict antirealism as an insane and disreputable view that no reasonable person would endorse. BB’s remarks suggest:

Antirealism is “crazy”

Antirealism isn’t worth taking seriously

Antirealism falls in the category of allegedly absurd views like external world skepticism

Members of this category don’t have much significance

Members of this category are rare

Members of this category exist largely as curiosities for philosophers

This is mostly just tendentious rhetorical sneering that reveals more about BB’s attitude towards a view than any substantive philosophical claims. What I find more puzzling is the suggestion that skeptical views are especially rare. It is very common for philosophers to hold skeptical positions. See the 2020 PhilPapers survey. To provide just a few examples:

15% endorse scientific antirealism

29.8% deny the hard problem of consciousness

11.2% deny free will

These are not tiny numbers, and represent only a very small sample of skeptical positions that appear in the PhilPapers survey. Taken in isolation, they might look fairly small, but with so many positions one can take, it would be unsurprising if a majority of philosophers held at least one “skeptical” position. In fact, 5.4% are external world skeptics. That’s 96 people who responded to that question: not an insignificant number of philosophers at all.

In short: it is common for philosophers to hold skeptical views. More generally, philosophers often hold unconventional or rare views that deviate from what most other philosophers think.

BB also trots out a lot of the mistakes I’ve documented in the past few years. Take this remark:

So if you think that the sentence that will follow this one is true and would be so even if no one else thought it was, you’re a moral realist. It’s typically wrong to torture infants for fun!

This is run of the mill normative entanglement. I’m an antirealist, and I think “It’s typically wrong to torture infants for fun!” I even think it’d be wrong even if no one else thought it was! Giving the impression that antirealism entails disagreeing with this is misleading. BB should know better.

BB also says:

We do not live in a bleak world, devoid of meaning and value. Our world is packed with value, positively buzzing with it, at least, if you know where to look, and don’t fall pray [sic] to crazy skepticism.

This is also normative entanglement. Antirealism only entails that we live in a world without stance-independent moral facts, not a world without “meaning and value”. The latter is a normative claim that is consistent with both realist and antirealist conceptions of meaning and value. Realists are not entitled to help themselves to the presumption that only realist conceptions of meaning and value are legitimate, and that therefore, if you’re an antirealist, you think the world has no meaning and value. Antirealists can both (a) reject moral realism and (b) reject realist conceptions of meaning and value, and hold that antirealist conceptions of meaning and value are correct.

BB does what many realists do: they drop any explicit indication of a realist conception of first-order terms like “meaning” and “value,” which gives the impression that antirealism rejects not only the realist’s conception of these notions, but any conception of these notions at all (as if only the realist’s conception of meaning and value are legitimate). I call this the halfway fallacy, and discuss why I think it’s a problem here.

BB also employs what I take to be objectionable rhetoric by suggesting that antirealism involves biting a bullet. I explain why I think this is a mistake here. The short version of this is simple: I not only deny moral realism, I also deny that there’s anything appealing about realism or any presumption in its favor. I don’t think rejecting moral realism involves biting a bullet any more than denying the existence of vampires does.

BB and other realists often try to frame moral antirealism as some kind of insane fringe view that only gibbering idiots would endorse. It’s never a good sign when critics have to go out of their way to craft a misleading narrative to try to make rival positions look bad. If the position really is so stupid and insane, the arguments themselves should be enough to demonstrate this without all the rhetorical fireworks.

3.0 Responding to “A Point About Methodology”

BB’s next section introduces phenomenal conservatism (PC). This is, roughly, the view that you are justified in believing that things are the way they seem so long as there isn't a compelling reason to give up those beliefs.

I don’t endorse phenomenal conservatism, but granting it for the sake of argument does very little (if anything) to strengthen the case for moral realism.

Phenomenal conservatism at best provides only private, personal “evidence” for a view: if you find that things seem a certain way to you, then you are to that extent “justified” (whatever that means) in believing those things.

It seems to me that moral realism isn’t true. PC does just as much to “justify” my antirealism as it does to justify the realist’s realism (if it seems to them that realism is true). PC is neutral with respect to which of these positions is correct, and does not distinctly favor realism or antirealism.

BB also proposes “wise” PC:

Wise Phenomenal Conservatism: If P seems true upon careful reflection from competent observers, that gives us some prima facie reason to believe P.

The use of “careful reflection” and “competent observers” provides a ton of wiggle room. I regard myself as a competent observer who has carefully reflected on moral realism, and the result is that I am even more confident it isn’t true. This revision to PC probably isn’t going to achieve much, since it will just prompt a pivot towards discussion of what careful reflection and competent observation entails, and how we can determine who meets these conditions.

BB brings up some responses to PC, but I don’t care about those so I will move on.

4.0 Responding to, “2 Some Intuitions That Support Moral Realism”

BB begins with the following:

The most commonly cited objection to moral anti-realism in the literature is that it’s unintuitive. There is a vast wealth of scenarios in which anti-realism ends up being very counterintuitive.

BB does something I frequently criticize: describe things as intuitive or counterintuitive without qualification. Counterintuitive to who? No claim is intrinsically intuitive; how “intuitive” something is depends on the intuitions of the person evaluating the claim. I don’t find moral antirealism counterintuitive, nor do I think there are any scenarios where it is counterintuitive. It better accords with my intuitions, and I don’t think there are any good reasons to accord more weight to BB’s or anyone else’s intuitions than my own. So claims that it’s “counterintuitive”, in and of themselves, don’t have much dialectical force. One could say “I find such claims implausible” and then speculate about whether your readers will, too.

BB goes on to say each version of antirealism has distinct counterintuitive implications:

We’ll divide things up more specifically; each particular version of anti-realism has special cases in which it delivers exceptionally unintuitive results. Here are two cases

I now turn to these cases.

4.1 The first “counterintuitive” case

Here’s BB’s first case:

This first case is the thing that convinced me of moral realism originally. Consider the world as it was at the time of the dinosaurs before anyone had any moral beliefs. Think about scenarios in which dinosaurs experienced immense agony, having their throats ripped out by other dinosaurs. It seems really, really obvious that that was bad.

Of course it was bad. This in no way demonstrates anything counterintuitive about any form of antirealism. An antirealist can simply regard this as bad.

BB continues:

The thing that’s bad about having one’s throat ripped out has nothing to do with the opinions of moral observers. Rather, it has to do with the actual badness of having one’s throat ripped out by a T-Rex.

So BB describes a scenario, says that it “seems really, really obvious that that was bad,” which is an ambiguous remark that can be interpreted in ways that are trivially easy to show are consistent with antirealism, then follows this by simply asserting that it was bad in a way only consistent with realism. So BB’s first demonstration of something counterintuitive is to present an innocuous scenario then assert that it’s bad in a realist sense.

When I say that such scenarios are bad, I am telling you something about what I think about them: That I disapprove of them, regard them as undesirable, don’t want them to occur, and so on. It absolutely has something to do with the opinion of a moral observer: me. Here, BB says this has to do with “actual badness.” Here we have the use of a deceptive modifier, “actual” (see this article where I elaborate on how realists misuse deceptive modifiers).

The implication here is that if something were bad in some nonrealist sense, like a subjectivist sense, then it isn’t actually bad. Well, I don’t like the taste of shit. But I’m not a gastronomic realist (i.e., I don’t think there are stance-independent facts about whether food tastes good or bad). Does that mean the taste of shit isn’t “actually bad”? Should I just be indifferent to the taste of what I eat since there are no stance-independent normative facts about taste? I don’t know about you, but that strikes me as ridiculous.

Realists have no business claiming that only their conception of morality involves “actual” badness. Antirealism isn’t the view that nothing is “actually” good or bad. It’s a rejection that anything is good or bad in the realist’s sense. The antirealist is not obliged to grant that things only could be good or bad in the realist’s sense, i.e., would only “actually” be good or bad if they were stance-independently good or bad: we can reject this, too. And I do. I think the only sense in which anything is “actually” good or bad is in an antirealist sense. What you see here is, yet again, rhetoric and misleading framing and a presumption in favor of realism all through BB’s characterization of the dispute.

So far, BB has not presented any substantive critique of antirealism. BB appears to have presented a scenario and asserted that things in that scenario are bad in a realist’s sense. Assertions aren’t arguments. Perhaps a reader is supposed to read this and go “yea, I think it’s that way, too.” I’d be surprised if as standard a scenario as this prompted someone to reflect or recognize they had realist intuitions where they didn’t previously. I suspect instead this would simply prompt them to affirm whatever they were already disposed to affirm. But perhaps this scenario would somehow prompt some readers to recognize realist inclinations. I don’t know. Whatever the case may be, this scenario does not strike me as having much argumentative force.

BB continues:

When we think about what’s bad about pain, anti-realists get the order of explanation wrong. We think that pain is bad because it is — it’s not bad merely because we think it is.

Again, who is “we”? BB makes a vague and unqualified assertion about how “we” think: that “we” think things are bad because they are; they’re not bad because we think they are. Again, this is simply an assertion. Assertions aren’t arguments. This is the very thing BB is supposed to be demonstrating. Not simply declaring. Insofar as this assertion is supposed to characterize how anyone other than BB thinks: that’s an empirical claim, and not one BB is entitled to assert as true. This isn’t how I think. When I say things are “bad” the causality is in the antirealist direction: their badness is constituted by my attitude towards them. I think it’s BB who gets the causal story backwards. BB has presented absolutely nothing that would suggest he’s right about this and I’m wrong. What we have here are mere assertions.

4.2 BB’s second “counterintuitive” case

BB’s second scenario is:

The second broad, general case is of the following variety. Take any action — torturing infants for fun is a good example because pretty much everyone agrees that it’s the type of thing you generally shouldn’t do. It really seems like the following sentence is true

“It’s wrong to torture infants for fun, and it would be wrong to do so even if everyone thought it wasn’t wrong.”

It seems to who? That sentence doesn’t “seem true” to me. It’s also unclear what it means. Is BB asking me whether I’d think torturing infants for fun would be wrong, relative to my standards, even if everyone else thought it wasn’t wrong? If so, that’d be consistent with antirealism: I do think it’d be wrong even if everyone else thought otherwise.

If, instead, I am included in this scenario, then I’d be being asked whether it’d still be wrong even if I thought it wasn’t wrong. But note that there are two different versions of me: the actual me evaluating this scenario, and a hypothetical me with repugnant moral values. Again, who is this statement being relativized to? To the actual me or the hypothetical me? If you ask me whether torturing infants for fun would still be wrong relative to my actual moral values even if a hypothetical version of me thought it wasn’t wrong, then the answer is, again, still consistent with antirealism: yes, it’d still be wrong, relative to my actual values.

It wouldn’t be wrong relative to the hypothetical version of me’s values, but this is trivially true for the antirealist: if on my view what it means for it to be wrong just is whether it is wrong relative to an evaluative standard, then if you say “suppose everyone held an evaluative standard according to which it wasn’t wrong,” then it would be trivially true that the action in question wouldn’t be wrong relative to the evaluative standards of anyone in that hypothetical. This is, again, trivially true. It’s like asking:

“If nobody liked the taste of chocolate, would anyone like the taste of chocolate?”

The answer will be a definitive “of course not.” BB’s scenario exploits ambiguity to confuse readers into having the misleading impression that if you’re a moral antirealist, that you’re somehow contingently okay with torturing babies for fun in a nontrivial sense. After all, if BB wants to show there’s something mistaken or wrong or repugnant or unappealing about moral antirealism, it won’t do to say “if you thought torturing babies for fun wasn’t wrong, would you think torturing babies for fun wasn’t wrong?” Conditional on antirealist views that relativize moral claims, that’s all such a question would amount to, so it’d be trivial. The only way for BB’s scenario to “work,” i.e., to not ask something trivial, is if we employ a realist notion of wrongness in here somewhere. In that case, though, the scenario is superfluous: it may ostensibly be intended to serve as an intuition pump, but since it’s worded in an ambiguous and misleading way, whatever value it has for this purpose is inextricably entangled with its ambiguous and confounding aspects; adequate disambiguation functionally amounts to simply asking the reader if torturing infants for fun is stance-independently wrong. The “scenario” is at best a mere recapitulation of asking someone if they’re a realist towards a specific moral issue, and at worst is actively misleading.

The futility of this scenario is eclipsed by the next example BB gives:

Similarly, if there were a society that thought that they were religiously commanded to peck out the eyes of infants, they would be doing something really wrong. This would be so even if every single person in that society thought it wasn’t wrong.

I cannot stress this enough: I am an antirealist, and I completely agree with BB. That’s because whether *I* think something is morally right or wrong isn’t determined by whether individuals or societies approve of a particular action. I don’t think that if some society is okay with plucking out the eyes of infants, that this somehow makes it okay. Whether it’s morally good or bad relative to my values depends on my values. BB gives the impression here that we should actually interpret what he’s asking in the previous scenario to whether something is morally right or wrong depends on the values of the agents performing the action, i.e., agent relativism. Agent relativism holds that whether an action is right or wrong is determined by the standards of the agent performing the action or, in the case of agent cultural relativism, the standards of that agent’s culture.

This form of relativism has the unusual but noteworthy implication that if Alex thinks torturing babies for fun is good, then it is, in fact, good, in such a way that I and everyone else must respect: if Alex wants to torture babies, and attempts to do so, the rest of us are obliged to regard this as “good” and to stand aside. In other words, agent relativism imposes constraints on everyone else’s actions that are binding on those people independent of their own goals, standards, and values. It functions a lot more like realism than any antirealist view I’d consider remotely acceptable. I often refer to it as “a la carte realism.” While not technically a form of moral realism, since moral facts are stance-dependent, its most objectionable elements are, ironically, precisely the respects in which it most closely resembles moral realism. Critics of antirealism often depict relativism as if agent relativism were the only form of relativism.

Antirealists do not have to think that an action wouldn’t be wrong if the people performing that action think it’s not wrong. Our own evaluative standpoints don’t have to shift and move in accord with other people’s moral standards. We can (and I do) always judge in accord with our own standards. Moral antirealism doesn’t entail agent relativism. Insofar as BB’s scenario conflates antirealism and agent relativism, this scenario not only doesn’t serve as any substantive critique of antirealism or bolster the case for realism, it serves only to muddle the dispute.

5.0 Discovery vs. invention

BB next employs another line of reasoning that does nothing to bolster the case for realism:

This becomes especially clear when we consider moral questions that we’re not sure about. When we try to make a decision about whether abortion is wrong, or eating meat, we’re trying to discover, not invent, the answer.

Again, note that BB simply asserts a realist-friendly reaction to this, rather than presenting anything like an argument. Worse, this is a false dichotomy. The impression BB gives is that when it comes to moral deliberation, we have two options:

Discover the stance-independent moral truth

“Invent” an answer

I reject both of these options. BB gives the impression that if you don’t deliberate with an eye towards stance-independent truth, that you just make-up whatever answer you want. This gives the impression that an antirealist is relegated, when it comes to moral deliberation, to a transparently constructive and blatantly arbitrary process of simply deciding in the moment whether they’d like to torture babies or whatever. This is not at all what a moral antirealist is limited to. Consider everyday nonmoral decisions: what career to choose, what clothes to buy, what to have for lunch. Suppose, for a moment, that in these scenarios one’s goal is to optimize with respect to one’s own goals and preferences. That is, suppose we’re not gastronomic realists and fashion realists and so on: when we are trying to decide what clothing to buy, our goal is simply to buy clothing we want to wear and that will optimize for our goals.

Would this mean we instantly and immediately know which clothing to buy at the store?

Of course not. What clothing will best serve our interests is not immediate or transparent to us. We may have to think:

I like green more than blue, but I already have more green than blue shirts, so this one’s out

Hmmm, I like the texture of this one, but at that price? Perhaps not

This one is nice, but isn’t this kind of going out of fashion?

This one’s a bit too tight around the arms, but the other one’s too long…

Even when making decisions entirely with respect to our own goals, preferences, and values, and for matters of deliberation where I suspect many readers will agree that, at the very least, we’re not presumptively being realists about the matter at hand, we still have to deliberate and think things through. We don’t simply invent our answers.

When it comes to morality, I don’t invent my values, or invent solutions to moral dilemmas. Yet I still experience moral dilemmas. My moral values are not transparent and obvious to me, nor their application to specific cases is not obvious, nor the degree to which I weigh one moral consideration against another, and so on.

In a certain respect, then, the antirealist can “discover” what is morally right or wrong relative to their own values, preferences, standards, epistemic frameworks, and so on. If BB’s use of “discover” is, by stipulation, limited to discovering the stance-independent moral facts, then BB has presented a genuinely false dichotomy. If, instead, its flexible enough to be inclusive of conceptions of discovery consistent with antirealism, then an antirealist can choose “discover” just like the realist, then the dichotomy loses all its force and is no longer presents a distinction that favors the realist.

BB adds this line:

If the answer were just whatever we or someone else said it was — or if there was no answer — then it would make no sense to deliberate about whether or not it was wrong.

An antirealist is not obliged to characterize moral deliberation in terms of an action being right or wrong entirely on the basis of whether I “say” it is. We can and do employ self-imposed constructive procedures for determining whether specific actions are morally right or wrong. For instance, a moral antirealist can be personally committed to utilitarianism, in that they favor maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering. They may still struggle with the question of whether abortion is moral or immoral because they may not know whether any given abortion policy or stance towards abortion would, if implemented, maximize utility. The idea that if you’re an antirealist that it’d make no sense to deliberate is simply mistaken.

As far as what one would do if “there was no answer,” this again needs to be disambiguated. If there was no answer to whether abortion was morally right or wrong in a realist sense? Or in some other sense? Even if nothing is morally right or wrong in the realist sense, and even if that’s the only sense in which anything is or could be morally right or wrong, such that nothing is morally wrong or wrong, well, sure, then it wouldn’t make sense to deliberate about whether abortion is “morally right” or “morally wrong.”

So what? What follows from that? Does that mean that the error theorist who holds such a view should just stop thinking about abortion, or not care? No. Absolutely not. Even if you don’t think abortion is, technically speaking, “morally right,” or “morally wrong,” you can still deliberate about what kind of society you want to live in, and what policies would optimize for your preferences, and so on. Nothing about the inability to deliberate specifically about whether something is stance-independently right or wrong has any practical consequences for deliberating about what would optimize for your personal values and preferences. Realists routinely give the impression of something like a “realism or nihilism” gambit: that if you don’t accept a realist framing of deliberation or whatever, that you’re left with nothing. This is complete nonsense.

Imagine if I did the same for taste: You have two options:

Accept that there are stance-independent gastronomic facts governing what you should or shouldn’t eat, according to which when, setting aside all dietary, ethical, financial,and other considerations, and your sole consideration is how good or bad food tastes, you are obligated not to eat foods that taste better to you, but to eat foods that are stance-independently tasty, i.e., tasty independent of how they taste to you or anyone else

Be completely indifferent to taste decisions. You have zero rational basis for preferring to eat foods that taste better to you than ones that taste terrible. It makes absolutely no sense to prefer eating chocolate over feces, or to eat bread instead an equally nutritious and edible pile of nutritive goo that tastes like vomit.

This is, of course, ridiculous. If you reject (1) you’re not obliged to accept (2), or vice versa. I don’t think there are stance-independent facts about what food is tasty or not. This in no way makes it impossible or nonsensical for me to deliberate about what to eat for lunch. It also does not entail that I invent my food preferences.

Likewise, I’m not limited to either discovering stance-independent moral facts or just “inventing” moral truths on a whim. BB sets up what is at best a false dichotomy that an antirealist can trivially circumvent.

6.0 Arguing about morality

Next, BB says:

Whenever you argue about morality, it seems you are assuming that there is some right answer — and that answer isn’t made sense by anyone’s attitude towards it.

Again, “it seems.” It seems to who? It doesn’t seem this way to me.

Once again, BB gives the impression that some feature of ordinary thought, like deliberation, or in this case, argumentation, presupposes realism. This is not true.

When people argue about things, they can and do appeal to intersubjective and shared goals and values. Suppose you and I are both committed antirealists and utilitarians. We could, given these commitments, argue about public policy or whether an action was right or wrong relative to our shared moral frameworks. If I argue with a complete stranger, I can and typically do intend to appeal to their own values, or I may wish to prompt them to reconsider their stance or commitments. They may be favoring a policy I dislike and don’t want implemented, so I may seek to get them to recognize this policy isn’t something they’d approve of on reflection. This does not require me to think that they must reflect on what the stance-independent moral facts are. I might just be trying to get them to realize they’re being inconsistent, or a bit of a jerk.

Furthermore, people routinely argue with the intention of achieving their goals, rather than arriving at the truth. Call this “coordination argumentation,” rather than “truth-targetd argumentation,” just to pick the first terms that came to mind. People haggle about the price of goods. This doesn’t entail “price realism.” Friends argue about what pizza toppings to get when ordering pizza. This doesn’t entail “pizza topping realism.” People argue because they want things and other people want things and they need to negotiate.

Absolutely nothing about the fact that people argue lends itself to moral realism. Antirealists can and do argue all the time. We want things, and we frequently assume others do, too. Many arguments are rooted in these simple facts.

In this case, BB seems to think the way people argue implies they think there’s a stance-independently correct answer. But I don’t think BB has shown that this is the case. It instead appears to me that BB is reporting on how things seem to him. I would invite BB to consider that his conception of how things seem may be predicated on simplistic and inaccurate picture of the reasons and motivations people would have for arguing.

Lastly, it’s worth noting just how weak this point would be even if it were true. Suppose when many people argued about moral issues they were supposing some type of moral realism. That might suggest a presumption of moral realism was baked into…what? Much contemporary English? The psychology of Americans? That’s hardly a powerful source of evidence for moral realism.

What BB seems to be trying to show here, which is typical of realist arguments, is that people are generally inclined towards realism, and that perhaps the reader is already inclined towards realism. I don’t think these attempts are successful, but even if they were, they’d establish very little: a very weak presumption in favor of realism. Nothing amounting to a substantive argument in its favor. You can try to build a cumulative case off of a bunch of weak lines of evidence like this, I suppose.

BB goes on to consider some potential rejoinders. They’re not very good, but let’s have a look at the second one (the first is too weak to bother with):

Principle 2: confirmation is needed for a believer to be justified when people disagree with no independent reason to prefer one belief or believer to the other.

BB responds:

Very few people disagree, at least based on initial intuitions, with the judgments I’ve laid out. I did a small poll of people on Twitter, asking the question of whether it would be wrong to torture infants for fun, and would be so even if no one thought it was. So far, 82.6% of people have been in agreement.

This is not a good response. First, BB claims that “Very few people disagree” with the judgments he’s presented. BB makes a vague, underspecified empirical declaration about the psychology of some unknown population of people. What evidence does BB present? A Twitter poll. Twitter polls of the people who see BB’s posts are not representative of any meaningfully relevant population of people. Do these findings generalize to people in general? Who knows, but probably not.

Note that BB has conducted what amounts to an empirical test of people’s metaethical views. There are several limitations with this measure, all of which center on the lack of rigor and care taken to construct a good measure and to assess its validity.

First, we have little information about the representativeness of the sample. That is, whatever proportion BB obtains in conducting this survey, we don’t know how well this proportion represents how people in general would respond. Respondents may be disproportionately likely to agree with BB, or even to disagree.

Furthermore, the results may not be independent; that is, people could potentially see other people’s responses or see comments about those responses prior to responding to the survey.

Third, we have little direct evidence about how participants interpret the question that was asked. This is essential, since unintended interpretations are irrelevant for evaluating a particular hypothesis.

The study is likely also underpowered.

Furthermore, when you present ambiguous, poorly-phrased, and misleading questions, the proportion of people who judge superficially in the direction you find favorable isn’t a good indication that they share your specific position. It’s very, very tricky to craft appropriate questions for probing untrained people’s metaethical judgments. I developed this position because I wrote my dissertation specifically on this topic. BB, along with philosophers in general, underestimate the degree to which ambiguity, pragmatic considerations, normatively loaded remarks, and other factors can contribute to people’s responses to scenarios (especially dichotomous or forced-choice scenarios that restrict one’s answers to a simple, e.g. yes/no) being diagnostic of whether they endorse the position you think they do.

My colleague David Moss and I wrote a short paper addressing this issue which you can find here. The problems we outline here only scratch the surface. It’s incredibly difficult for nonphilosophers to respond to philosophical scenarios in a diagnostic way even when you carefully attempt to disambiguate those questions and avoid biasing factors. BB doesn’t appear to me to put even minimal effort into doing this, and, if anything, seems to me to dial up the ambiguity and biasing aspects of the questions BB poses. As such, I don’t think people’s responses to these questions would be meaningful, anyway.

What we’d really need to know is why people responded in one way or another, and it may turn out in many cases that the reason why had very little to do with a clear and distinctive endorsement of a specific metaethical position, to the exclusion of other, irrelevant considerations (e.g., normative considerations). Realists routinely wrap their framing of realist positions up in a confounding bow, such that normatively desirable implications are entangled with endorsing the realist’s position, while unappealing, repugnant, monstrous, or stupid notions are entangled with the antirealist’s view. You’d need to disambiguate these to show that people favor realist responses for their own sake. Realists presenting scenarios almost never do this, and BB’s scenarios are no exception.

Of course, these findings are only informative if the measures BB used were valid. So even if we set aside the fact that we have almost no reason at all to think BB’s results are representative of people in general, or of any informative population of people at all, there’s still the question of whether BB asked a valid question; that is, a question that consistently and reliably allows us to distinguish people’s views in accord with the stipulated operationalizations; in this case, presumably the goal is to distinguish realists from antirealists. BB simply hasn’t done the work to show that a Twitter poll is sufficient to provide much substantive evidence that his position is widely shared among any meaningful population of people.

Yet one of the most critical deficiencies of appealing to such evidence is that we already have a wealth of more carefully designed empirical studies on how ordinary people respond to questions about metaethics. Such studies have been designed by researchers with the knowledge and training to devise such measures, were gathered under more careful conditions, feature larger sample sizes, feature a wide variety of measures, and employ measures that have been refined for well over a decade to account for and avoid the many methodological pitfalls myself and others have identified with measures of metaethics. Why would BB conduct a flimsy online survey, when there’s already an entire body of empirical literature on the question? Why not appeal to that empirical literature?

Conducting a survey like this is like using a flimsy personal poll as evidence for the proportion of atheists in the United States, while making no mention of Pew or Gallup data. It’s strange. If I conducted a survey of my friends and found most were atheists, I doubt anyone would take this as good evidence that most people are atheists. Does BB not know that there’s already research on metaethics? Does BB not care? Does BB think his own question is better than all the research out there? Thinking you can establish that most people agree with you by conducting a Twitter poll, which will be visible primary to people who follow you, and will involve a self-selected sample, and for which you’ve shown no indication of having validated or workshopped to iron out ambiguities or confounds in the wording, is bizarre. There’s a whole literature not just on how nonphilosophers think about questions like these, but a literature that I myself am a part of that evaluates the validity of these measures.

Even well-trained psychologists and philosophers who attempt to very carefully solicit people’s metaethical responses using a variety of methods under far more rigorous conditions than BB’s employed struggle to do so. BB’s survey is, to put it bluntly, almost totally uninformative. It’s also weird that BB didn’t include a link to the poll or even what question was asked. I don’t think there’s anything suspicious about that, but it suggests to me an attitude of complacency and lack of awareness for the challenges of constructing a valid question (i.e., a question that actually tells you what you want to know).

I’ve discussed this so many times it’s become tedious: the best available empirical evidence does not suggest that most people are moral realists, act like moral realists, think like moral realists, speak like moral realists, endorse moral realism, or in any way favor moral realism. The bulk of the psychological research on folk metaethics goes back about twenty years. Over the past two decades, myself and others, such as Thomas Pölzler, Jennifer Wright, James Beebe, Taylor Davis, and David Moss, to name some of the authors involved, have identified methodological shortcomings in earlier research, and have sought to correct for those shortcomings. Newer, and more robust empirical studies tend to find very high rates of antirealism. See, for instance, these results from Pölzler and Wright (2020):

This is Fig. 1, on page 73 of Pölzler and Wright (2020).

Or consider this more recent, cross-cultural study from Pölzler, Tomabechi, and Suzuki. They employ a range of measures and ways of coding the data, but even if you use their most conservative measure, which amplifies realism to a much greater extent relative to their other methods you still get results like this:

The measures used in these studies may not be valid, or may suffer methodological shortcomings. But they’re more informative than BB’s Twitter poll. At the very least, I’d hope such findings give BB and others pause in the constant and insistent presumption that most people are intuitive moral realists. The data just does not seem to point in this direction at the moment.

BB goes on to say:

Also, those who disagree tend to have views that I think are factually mistaken on independent grounds. Anti-realists seem more likely to adopt other claims that I find implausible.

It seems like BB is providing biographical details. If you share BB’s other views, then maybe this will have some traction. Otherwise, I don’t think it carries much weight if one’s goal is to present a case for moral realism.

Next, BB says:

Additionally, they tend to make the error of not placing significant weight on moral intuitions.

It’s not clear if this is true. Which intuitions? Normative intuitions or metaethical ones? BB’s remark here simply isn’t clear. If BB is talking about metaethical intuitions, most antirealists I know find realism intuitive and put, if anything, more stock into intuitions than I think they should. I’m a bit of an outlier in that I don’t have realist intuitions in the first place. That may put me in good company relative to the general population, since I don’t think they typically have realist intuitions either, but at least among philosophers I think BB’s claim is probably not true. It’s hard to say because it’s too underspecified to readily evaluate.

BB then says:

Thus, I think we have independent reasons to prefer the belief in realism.

We have independent reasons because antirealists tend to hold views BB finds implausible? So is BB just assuming his readers share his intuitions? Maybe they do, but this is starting to look an awful lot like preaching to the choir.

BB next says:

It also seems like a lot of the anti-realists who don’t find the sentence “it’s typically wrong to torture infants for fun and would be so even if everyone disagreed” intuitive, tend to be confused about what moral statements mean — about what it means to say that things are wrong.

Note, again, that BB is talking about how things seem without qualification. Seems to who? Antirealists don’t seem confused to me. If BB thinks we’re confused, it’s BB’s job to present arguments or evidence for that. Simply reporting that “it seems” we’re confused is hardly an argument. I don’t think we are confused. Rather, we simply disagree with you about what those statements mean or what the people making those statements mean. Disagreement is not confusion.

BB then says:

I, on the other hand, like most moral realists, and indeed many anti-realists, understand what the sentence means. Thus, I have direct acquaintance to the coherence of moral sentences — I directly understand what it means to say that things are bad or wrong.

Again, this is a mere assertion. Why should I grant that BB and most moral realists “understand what the sentence means”? BB hasn’t presented any substantive arguments or evidence. What are we to conclude? That BB has demonstrated he understands what a sentence means because he conducted a Twitter poll? BB claims to have direct acquaintance, but what entitles BB to such a claim? Why couldn’t I similarly assert that I, contra BB, am acquainted with the meaning of these terms, and that what they mean better accords with antirealism than realism? Again, BB is not presenting arguments, but just asserting things, and, at best, providing very feeble evidence that is, if anything, overshadowed by evidence to the contrary. Carefully constructed psychological studies are at least better than improvised Twitter polls conducted on one’s personal Twitter account.

BB next says:

If it turned out that a lot of the skeptics of quantum mechanics just turned out to not understand the theory, that would give us good reason to discount their views. This seems to be pretty much the situation in the moral domain.

BB has presented no substantive arguments or evidence that I or any other moral antirealists don’t understand “the moral domain,” or what moral claims mean, or anything of the sort. As far as I can tell, this is simply asserted. There’s also no specification about what proportion of antirealists misunderstood, nor is any supporting evidence of any specific antirealist not understanding anything in particular actually given. Who are these antirealists? What do they not understand? Why does BB think they don’t understand it?

7.0 Most philosophers are realists

Next, BB says:

Additionally, given that most philosophers are moral realists, we have good reason to find it the more intuitively plausible view. If the consensus of people who have carefully studied an issue tends to support moral realism, this gives us good reason to think that moral realism is true.

No, it doesn’t. I’ve addressed this at length in a nine-part series called The PhilPapers Fallacy, where I critique the notion that the fact that most analytic philosophers are moral realists is good evidence of moral realism. You can find that here, with the table of contents to the set of posts at the bottom. Here’s the synopsis, reproduced here:

People often appeal to the proportion of philosophers who endorse a particular view in the PhilPapers survey as evidence that a given philosophical position is true. Such appeals are often overused or misused in ways that are epistemically suspect, e.g., to end conversations or imply that if you reject the majority view on the matter that you are much more likely to be mistaken, or that you’re arrogant for believing you’re correct but most experts aren’t.

That most respondents to the PhilPapers survey endorse a particular view is very weak evidence that the view is true. Almost everyone responding to the survey is an analytic philosopher, and the degree to which the convergence of their judgments provides strong evidence is contingent on, among other things, (a) the degree to which analytic philosophy confers the relevant kind of expertise and (b) the degree to which their judgments are independent of one another.

There is good reason to believe people trained in analytic philosophy represent an extremely narrow and highly unrepresentative subset of human thought, and there is little evidence that the judgments that develop as a result of studying analytic philosophy are reflective of how people from other populations, or people under different cultural, historical, and educational conditions, would think about the same issues (if they would think about those issues at all).

Since most philosophers responding to the 2020 PhilPapers survey come from WEIRD populations, most of them are psychological outliers with respect to most of the rest of humanity. Their idiosyncrasies are further reinforced by self-selection effects (those who pursue careers in philosophy are more similar to one another than two randomly selected members of the population they come from), a narrow education that focuses on a shared canon of predominantly WEIRD authors, and induction into an extremely insular academic subculture that serves to further reinforce the homogenization of the thinking of its members. As such, analytic philosophers are, psychologically speaking, outliers among outliers among outliers.

At present, there is little evidence or compelling theoretical basis for believing that human minds would converge on the same proportion of assent to particular philosophical issues as what we see in the 2020 PhilPapers survey results if they were surveyed under different counterfactual conditions.

There is also little evidence nor much in the way of a compelling case that analytic philosophy confers expertise at being correct about philosophical disputes. The presumption that the preponderance of analytic philosophers sharing the same view is evidence that the view is correct is predicated, at least in part, on the further presumption that the questions are legitimate and that mainstream analytic philosophical methods are a good way to resolve those questions. Both of these claims are subject to legitimate skepticism. Analytic philosophy is a subculture that inducts its members into an extremely idiosyncratic, narrow, and comparatively homogeneous way of thought that is utterly unlike how the rest of humanity thinks. It has little track record of success and little external corroborating evidence of its efficacy.

Critics are not, therefore, obliged to confer substantial evidential weight on the proportion of analytic philosophers who endorse a particular philosophical position. Resolving how much stock we should put in what most philosophers think rests, first and foremost, on resolution about the efficacy of their methods.

8.0 Responding to “What if the folk think differently”

In the next section, BB addresses the suggestion that most people may not be realists. BB begins by saying:

I’m supremely confident that if you asked the folk whether it would be typically wrong to torture infants for fun, even if no one thought it was, they’d tend to say yes.

I already addressed this above: this is a terrible question that’s ambiguous and not a good way to measure whether respondents are realists or not. If BB thinks otherwise, BB is welcome to do empirical research that establishes the validity of such a question as a diagnostic tool for evaluating whether nonphilosophers are realists.

BB then says:

Additionally, it turns out that The Folk Probably do Think What you Think They Think.

BB seems to think this article justifies his claim that moral realism is an intuitive, commonsense view. Yet this seems to be based almost entirely on taking the title of the paper literally. Titles of papers published in journals are often intentionally cute or provocative. Taking this one at face value is bizarre and a little embarrassing. This paper does not show that philosophers probably think what you think they think. How could it? What you think they think will depend on what you think they think. I think most people are not realists. Does that mean that they probably aren’t realists?

BB could say that if most philosophers think most nonphilosophers are realists, that this is what’s probably true: that it’s a statistical claim, i.e., that most nonphilosophers probably think what most philosophers think they think. And perhaps most philosophers think most people are moral realists. That seems plausible enough. So, does the paper establish this? That most nonphilosophers probably think what most philosophers think they think?

No, not really. Before considering this, note a few things:

First, this is only a single study. As Scott Alexander warns, one should beware the man of one study. It’s more than a little questionable for BB to trot out one study that purportedly supports his claims. I could provide at least a dozen that support my contentions, probably more than that, in large part because I myself conducted many of these studies.

Second, it at best provides extremely indirect evidence that most nonphilosophers are moral realists. Note that, in contrast, the data I’d appeal to directly addresses the question of whether the folk are moral realists (and suggests, I contend, that most of them aren’t).

Finally, there is the study itself. Does the study provide a good justification for thinking most people are moral realists, or that realism is intuitive or a commonsense view among most nonphilosophers? Not even close. Unfortunately, BB persisted in making this claim some time later, and was much more explicit about it. This occurred in a Facebook exchange on Joe Schmid’s wall, where BB stated that:

But philosophers are usually write [sic] about what the folk think.

This claim is beyond wrong. Right about what they think in what context? Without context? Are philosophers usually right to any arbitrary level of specificity? With respect to any claim about what the folk think? This remark displays BB’s abject ignorance when it comes to making clear, precise, and appropriately well-specified claims. Suppose I found that if you gave doctors a detailed case report, told them that the patient had one of two diagnoses, (1) or (2), and you found that doctors chose the correct diagnosis at significantly higher rates than chance, would you conclude that “doctors are usually correct in their diagnoses of illnesses”?

Absolutely not. Because most doctors aren’t diagnosing people under such highly narrow, specific, tailored conditions. If you wanted to show that doctors generally make accurate diagnoses, you’d need enough data to generalize from the results of your studies to the actual decisions doctors make in the scenarios you’re talking about. It is not enough to show that in some lab study you get some result consistent with a hypothesis that therefore you’ve definitively established some claim based on generalizing from your results to whatever claim you make outside of that study. It is extremely difficult to establish the external validity of a particular study’s results; you often need a ton of data, or to triangulate on such a conclusion by appealing to a broad body of mutually corroborating literature, or to ground your interpretation of your data in a solid and well-supported theory, or to provide extraneous evidence that you’ve validated your measures…or, ideally, all of the above. Citing a single study this far removed from the conclusion BB wants to reach doesn't even come close to making a strong case for BB’s claims.

The only thing the study BB cites achieves is showing that if you give a handful of philosophers a description of a handful of unrepresentative study designs with the response options and conditions available to them, that they can predict whether there’d be a significant difference and what direction that difference is in. This is not very robust information. It doesn’t tell much about the degree of the difference and, more importantly, as I address below, it doesn’t tell you why there is such a difference. This is not a good way to determine whether philosophers know what the folk think, and it especially doesn’t justify generalizing from the cases featured in these studies to claims made outside the context of these studies. I reinvent the wheel a lot, but even if I have my limits. I addressed these points in the Facebook exchange with BB mentioned above, so I’ll simply reproduce that comment here, in its entirety:

Matthew Adelstein Here’s one issue.

The authors canvas four studies. These studies are:

Knobe, J., & Fraser, B. (2008). Causal judgment and moral judgment: Two experiments. Moral psychology, 2, 441-447.

Knobe, J. (2003). Intentional action and side effects in ordinary language. Analysis, 63(3), 190-194.

Livengood, J., & Machery, E. (2007). The folk probably don't think what you think they think: Experiments on causation by absence. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 31(1), 107-127.

Nichols, S., & Knobe, J. (2007). Moral responsibility and determinism: The cognitive science of folk intuitions. Nous, 41(4), 663-685.

The authors show that when you present the stimuli for these studies, that the surveyed population of philosophers that were asked about them were able to accurately predict the outcome of the studies most of the time. There are already a number of concerns with this framing, but I’ll set those aside for now to focus on some other issues.

(1) First, let’s look at who the participants in these studies were.

(i) Knobe & Fraser (2008): Two studies. The first was n=18 intro to philosophy students at UNC. I didn’t see a sample size for the second study, nor any other demographic info. It’s plausible they were all UNC students, but I’m trying to be quick here and didn’t look to see if this info is anywhere.

(ii) Knobe (2003): Study 1 and 2 consisted of 78 and 42 people in a Manhattan public park, respectively.

(iii) Livengood & Machery (2007): 95 students at the University of Pittsburgh

(iv) Nichols & Knobe (2007). All studies conducted with undergraduates at the University of Utah.

Taken together, these studies all reflect the attitudes and judgments of people responding to surveys in English in the United States. Most of the participants were college students. These studies were conducted in a particular cultural context: WEIRD societies. They were conducted on what were likely mostly WEIRD populations (though all of the studies did a bad job of providing significant demographic data), all of the studies had small samples, and most of the studies (3 of 4) were conducted on college students in particular.

WEIRD is an acronym that stands for “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic.” It was a term proposed to describe a clustering pattern of demographic traits characteristic populations that comprise the vast majority of research participants in psychology, and the vast majority of those conducting this research.

When it comes to making generalizations about how “the folk,” or people in general think, it is important to gather representative data. That is, you should sample from populations who are sufficiently representative of the population about which you wish to generalize that inferential statistics permits one to make judgments about that population based on the participants in one’s sample. If, for instance, if wanted to know whether most people in the United States were Taylor Swift fans, it would make no sense to survey attendees at a Taylor Swift concert, for the obvious reason that people attending the concert would be more likely to like Taylor Swift.

Why is this a problem for four studies that figure in Dunaway et al’s study? The problem is that all four studies were conducted in WEIRD populations. And WEIRD populations are psychological outliers. Along numerous measurable dimensions of human psychology, people from WEIRD populations tend to anchor one or the other end of the extreme of these distributions. Thus, not only are people from WEIRD populations often unrepresentative of how people in general think, they are often the *least* representative population available. They are, at a population level, psychological outliers with respect to most of the world’s population. The evidence for this is strong, and only continues to grow with time. And ALL FOUR of the studies reported here were conducted in WEIRD populations (for what it’s worth, they were probably also conducted primarily by people from WEIRD populations, which could influence the way questions were framed, how results were interpreted, and so on, introducing a whole slew of additional biases I’m not even addressing directly). As such, the original studies themselves have such low generalizability that they, themselves, don’t tell us about how “the folk” think. At best, they might tell us about how college students or people in public parks in Manhattan think, but it’s not at all clear that how people in these places think reflects how people everywhere think.

And if the original studies don’t even come close to telling us what “the folk,” think, how on earth is the ability for philosophers to accurately predict the results of these studies supposed to indicate that philosophers know what “the folk” think? The answer to this is very simple: it doesn’t. Even if we ignored every other methodological problem with these studies, the bottom line is that even under ideal conditions the findings reported in this study wouldn’t even come close to providing robust evidence of how nonphilosophers think about the issues in question. And there are many other methodological problems with these studies.

There are even bigger problems with generalizability when one focuses on the judgments of college students in particular. Indeed, in some cases, we have empirical evidence that people around the ages of those most likely to be undergraduates are disproportionately likely to be *unrepresentative* of people of other age groups. See, for instance, Beebe and Sackris’s (2016) data on this with respect to metaethical views, which shows that people around college age are less likely to give responses interpreted by researchers as "realist" responses and more likely to give "antirealist" responses.

In short, the studies themselves have such low generalizability that they don’t tell us what “the folk” think. At best, they might tell us what college students in the US or people in Manhattan parks think. And I do mean "at best": I doubt they are even successful at this modest goal. Yet what college students in the US or people in Mahattan [sic] parks think is unlikely to be representative of what most of the rest of the world thinks. As a result, the studies are not a good proxy for what “the folk” think.

Given this, even if philosophers could predict the outcomes of these studies, and even if those studies had valid measures, were correctly interpreted, and so on (all highly contestable claims in their own right), the findings don’t tell us what “the folk” think for one simple reason: the original studies themselves don’t tell us what the folk think.

Note that this alone is probably sufficient to undermine any strong claims about these findings. And yet there are still more problems with these studies. If anything, that the original study isn't a good indication of what Matthew seems to think it indicates is likely overdetermined by a variety of additional considerations, subsets of which would likely to be independently sufficient to severely limit what the study tells us.

References

Beebe, J. R., & Sackris, D. (2016). Moral objectivism across the lifespan. Philosophical Psychology, 29(6), 912-929.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and brain sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83.

In short, there is little reason to believe the studies themselves were representative of how “people” think, so even if philosophers could accurately predict the results of these studies, those studies lack the generalizability to tell us about how people in general think. Compound this with the fact that the four studies the authors examined are not representative of research on how nonphilosophers think, and you basically have a lack of generalizability squared. That is, you have an unrepresentative sampling of studies that are themselves unrepresentative. This alone is sufficient to cast serious doubt on BB’s claim that philosophers generally know how nonphilosophers think.

There are yet more problems, however. In follow-up comments, I raised the following concerns:

Joe Schmid & Matthew Adelstein See, I told you this would take a bit of work! Unfortunately, raising objections to a claim often requires more work and words than making the claim in the first place, whether that claim ultimately turns out to be correct or not. Note that even these considerations are truncated when it comes to raising problems for conducting studies on student and WEIRD populations.

And I didn't even get into problems with researcher bias (which empirical studies suggest does influence Xphi studies), low statistical power, problems of interpreting the results of the studies, the severe problem of stimulus sampling with these studies (see 1 below), the fact that 3 of the 4 studies include Knobe on the research project, which even further limits the representativeness of the studies, the fact that most of the studies are about or are adjacent to moral/normative considerations, which makes them unrepresentative of Xphi in general, the fact that the researchers selected studies based on whether the authors of those studies claimed the findings were “surprising”: this is a strange standard to choose, since the most important factor in having a paper accepted for publication in psychology is the novelty of the findings, and there are very strong norms in place for people to report that their findings are “surprising” or to use terms to indicate that one’s findings are novel, interesting, and ultimately worth publishing.

That is, we have good reasons to think people would call their findings “surprising” regardless of how surprising they were, because there are massive incentives in place to do so. And, at any rate, perhaps we should infer that Knobe is not a good judge of which findings are surprising before we leap to the conclusion that philosophers are really good inferring how nonphilosophers think. That seems like a far more parsimonious account of this particular set of four studies, given that Knobe was an author on three of them.

(1) Stimulus sampling: Here’s a general problem in a lot of research. Researchers will use a particular set of stimuli, such as a set of four questions, or four examples of some putative domain, and then generalize from how participants respond to that stimuli to how people think about the domain as a whole.

Suppose, for instance, I wanted to evaluate whether people “like fruit.” I need to choose four fruit to ask them about. You can imagine conducting two different studies:

(a) Ask about apples, bananas, oranges, and grapes

(b) Ask about durian, papaya, figs, cranberries

We ask people to rate how much they like each fruit on a scale (1 = hate it, 5 = love it), then average across the four fruits to get a mean fruit preference score. Would you expect the same results if we ran these two studies? I wouldn’t. And would you expect either study to tell us what people think about fruit in general? Again, probably not. Why? Because there’s no good reason to think set (a) or (b) is representative of “fruit” as a domain. First, of course some populations will vary in whether they prefer the fruits in (a) or (b) more, but setting aside this concern, suppose wanted to know just about fruit preferences in the United States. If so, (a) is going to win by a landslide. Yet neither (a) nor (b) would tell us about “fruit” as a domain. This is because (a) and (b) are unsystematic and nonrandomly selected: they don’t *represent* fruit as a domain, but instead reflect very popular and much less popular fruit (in the US), respectively.

When researchers run studies, if they want those studies to generalize to all people, they already face the steep challenge that their *participants* are typically not representative of people in general. Yet another huge problem which is almost totally ignored turns on considerations like those outlined above regarding fruit: researchers often want to genrealize [sic] from their *stimuli* to some broader category of phenomena. Yet, whereas they recognize and model the participants in their studies as a random factor, they almost never bother to model their stimuli as a random factor. In effect, they treat their stimuli as though it is perfectly representative of the domain about which it is intended to quantify over, even though (a) this is almost certainly not true and (b) even though there are statistical methods available for avoiding this presumption. Of course, the problem with (b) is that it’s harder to do, and will often result in your findings being far less impressive. Who is going to put in the work to produce less impressive results? Not anyone who wants to win the competition of getting more publications.

It would be absurd for me to go into much more detail than that here, so I’ll direct you to a blog post and an article which develop on this problem in greater length.

https://www.r-bloggers.com/.../the-stimuli-as-a-fixed.../

https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fxge0000014

Judd, C. M., Westfall, J., & Kenny, D. A. (2012). Treating stimuli as a random factor in social psychology: a new and comprehensive solution to a pervasive but largely ignored problem. Journal of personality and social psychology, 103(1), 54.

Why does all of this matter? For a very simple reason: The Dunaway et al. (2013) paper involves an analysis of four particular Xphi studies. Yet there is no good evidence, nor any good reason, to think that these studies are a representative sampling of Xphi studies in general. As such, not only does the study suffer from ridiculouslly low generalizability with respect to the participants in the study, there’s no good reason to think the studies themselves are representative of Xphi studies.

This results in a double-whammy of super low generalizability. Note, too, that (a) the criterion for study selection was explicitly nonrandom, (b) no principled methods were employed for randomly selecting representative studies, (c) Knobe is sole, first, and second author on three of the studies, further suggesting that we’re not dealing with a representative sample of Xphi studies so much as, at best, a representative sample of studies conducted by Josh Knobe (and even that’s questionable), further limiting generalizability, and (d) the studies are all on very closely related subjects: three are explicitly about causal judgments (and the other is about attributions of intentional action), and three are about moral/normative evaluation (including the one not included in the first category). This means that the studies cover an extremely narrow range of the subject matter of folk philosophical thought and of Xphi research in general. As such, we’re dealing with an extremely narrow slice of research: It’s mostly early Xphi research on causality and moral judgment conducted by Knobe and colleagues. And we’re supposed to conclude that the ability to predict the outcome of *those* studies years after they were published and percolated through the academy are a good indication that philosophers know how nonphilosophers think?

It’s incredibly difficult for psychologists to figure out how people think even with high-powered, representative, carefully-designed studies conducted by experts with years of experience. Researchers face methodological problems piled on top of one another. See here for example:

Yarkoni, T. (2022). The generalizability crisis. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 45, e1.

…Yet we’re supposed to believe that philosophers can infer how nonphilosophers think based on their ability to predict the outcome of a tiny, unrepresentative handful of small studies?

Followed by this comment:

Joe Schmid & Matthew Adelstein Oh, and I *also* didn't add that there's a paper criticizing the results of the Dunaway et al. (2013) paper that takes a different angle than mine, further piling on the problems with this study:

https://www.tandfonline.com/.../10.../09515089.2016.1194971

Abstract: "Some philosophers have criticized experimental philosophy for being superfluous. Jackson (1998) implies that experimental philosophy studies are unnecessary. More recently, Dunaway, Edmunds, and Manley (2013) empirically demonstrate that experimental studies do not deliver surprising results, which is a pro tanto reason for foregoing conducting such studies. This paper gives theoretical and empirical considerations against the superfluity criticism. The questions concerning the surprisingness of experimental philosophy studies have not been properly disambiguated, and their metaphilosophical significance have not been properly assessed. Once the most relevant question is identified, a re-analysis of Dunaway and colleagues’ data actually undermines the superfluity criticism."

Liao, S. Y. (2016). Are philosophers good intuition predictors?. Philosophical Psychology, 29(7), 1004-1014.

One of the most important points to stress is that, even if you can predict the results of a study, that does not necessarily tell you how the respondents to that study think. Such a claim relies on the presumption that you’ve interpreted the results of the study correctly, such that the observed response patterns in your data are the result of valid measures and that you’ve interpreted them correctly. Correctly predicting, for instance, that most people would choose a “realist response” over an “antirealist response” does not entail that most of the respondents are realists, since this would only follow if choosing what was operationalized as a realist response actually indicates that the respondent is a realist. This was a point stressed by Joe Schmid, in his response to BB:

Matthew, Lance already hit most of the nails on the head. My three main problems, which largely reiterate Lance’s, are:

(1) We can only conclude that the philosophers surveyed are good at predicting some folk responses to certain survey questions; this doesn’t mean they’re good at predicting folk views or intuitions. Survey questions are very faint indicators of folk views and intuitions — they’re hugely liable to unintended interpretations, ambiguities, spontaneous theorizing, and other confounds.

(2) The results are not justifiably generalized to philosophers’ abilities to predict folk views more generally. From the fact that philosophers can predict some folk’s responses to some survey questions from 4 papers [with relatively small sample sizes], it is incredibly hasty to conclude that they’re good at predicting folk survey responses more generally on the dozens or hundreds of surveys that have and might be conducted — let alone folk views on the thousands of philosophical questions more generally (as opposed to responses to survey questions), and let alone folk intuitions.

(3) The surveys are done on WEIRD populations; even if those survey responses were good indicators of the views and intuitions of the survey respondents, and even if philosophers are generally good at predicting these responses, that doesn’t mean philosophers are generally good at predicting the views and intuitions of ‘the folk’; we need some reason to think the WEIRD survey populations are representative of ‘the folk’ more generally, including non-WEIRD populations.

Point (1) is critical: predicting the results of studies does not entail that you can predict what people think.

Finally, we now have a decade of research showing that seemingly reasonable attempts to address exactly this question have historically failed because participants do not interpret questions about metaethics as researchers intend. I cannot stress enough that I am not basing this on a superficial evaluation of available data, but because I have personally spent the last decade specifically specializing in this exact question. I quite literally specialize in the methods used to determine whether nonphilosophers are moral realists. It is ludicrously difficult to devise valid measures. Even if the studies used in Dunaway et al. relied on valid measures, and that predicting the results of those studies entailed predicting what people think, this won’t necessarily generalize to the specific case of metaethics.

It is one thing to say that a given body of data has poor generalizability: that you aren’t justified in generalizing from a given body of data to draw inferences about some larger population in the absence of data to the contrary. But this is a case where we actually have quite a lot of evidence to the contrary. More importantly, those studies which have done the most to distance themselves from the methodological shortcomings of earlier studies tend to find fairly high rates of antirealist responses from participants. I talk about this at length on this blog, on my channel, and in my research. Simply put, there is no good empirical case that most people are moral realists, that most people find realism intuitive, or that moral realism is a “commonsense” view widely held by nonphilosophers. Given the current state of available evidence, BB just isn’t justified in suggesting otherwise. I don’t want to rehash my case against widespread moral realism here, so I’ll direct you to some of my other posts on the matter:

J. P. Andrew insists people are moral realists, but empirical data does not support this claim

J. P. Andrew: Let's schedule a debate on whether most people are moral realists

Watkins and the persistent (and probably false) claim that most people are moral realists

Unfortunately, despite specifically stating that he’d be interested in hearing what my objections were, BB never responded to Joe and my responses. I like to flatter myself that this is because we made a case too strong for BB to rebut, but threads always stop somewhere and I sometimes forget to reply or lose track of people’s responses.

In short: the Dunaway paper doesn’t license BB to claim that realism is a commonsense view.

9.0 A response to “Classifying anti-realists”

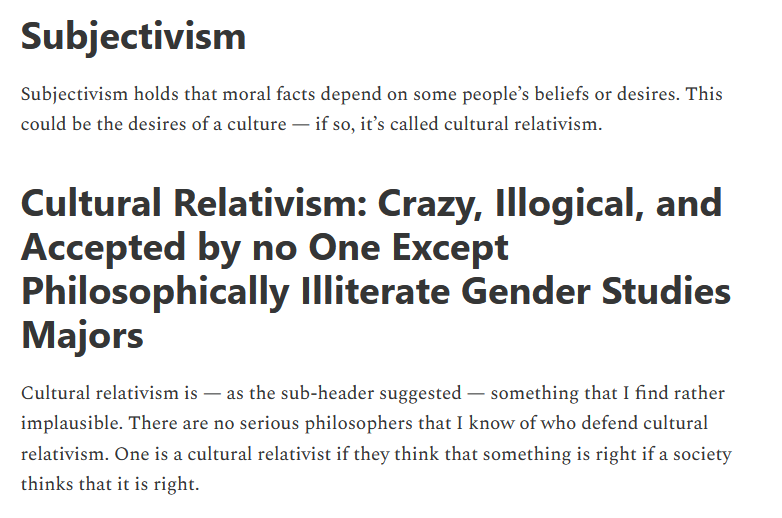

In the next section, BB says:

Given that, as previously discussed, moral realism is the view that there are true moral statements, that are true independently of people’s beliefs about them, there are three ways to deny it.

BB then lists noncognitivism, error theory, and subjectivism as the three ways to deny realism.

BB is, once again, incorrect. These are not the only ways to deny moral realism. I’m a moral antirealist, and I don’t endorse any of these positions. BB is echoing a claim made by Huemer in Ethical Intuitionism that there are only three possible antirealist positions. Huemer, like BB, is simply incorrect.

All three of these positions rely on a semantic thesis:

Error theory: Moral claims express propositions that purport to describe stance-independent moral facts

Noncognitivism: Moral claims do not express propositions and therefore cannot be true or false

Subjectivism: Moral claims are true or false relative to some standard

All three positions turn on a position about the meaning of moral claims.

They all appear to presume that there is a category, “moral claim,” and that all members of this category share the same semantic content, in that they, as a category, refer to stance-independent moral facts, express nonpropositional content only, or express claims that are true or false relative to some standard.

Here’s the problem: I don’t think there is any category like this. I don’t think there is a category of “claim,” a “moral claim,” that shares some specific semantic content. As an aside, I don’t even think there is a moral domain at all, so I’d have considerable objections to there even being a well-defined category of “morality” in the first place. But setting that aside, the characterization common among these positions of language and meaning is one that seems to rely on a conception of language that I don’t share. I endorse a language-as-use view, according to which words, phrases, and claims themselves don’t mean anything: it’s the people using language that mean things. This is captured by my slogan that “words don’t mean things; people mean things.” I cannot emphasize enough that I mean this literally: I do not think words mean anything. I think the people using words mean things, and the words are their means of conveying what they mean.

When we talk about the “meaning of moral statements,” I take this as an awkward and non-literal characterization of what people mean when they make moral statements, where “moral statements,” would be operationalized as some rough attempt at capturing a subset of ordinary discourse. I do think that when people make moral claims, they mean things, but:

I take facts about what people mean to be empirical questions

I endorse folk metaethical indeterminacy, i.e., I think that with respect to metaethical considerations, ordinary people rarely mean to express claims that determinately fit a realist or antirealist analysis at all