My, what weird facts you presuppose!

Twitter Tuesday #42

If you enjoy this article, please hit the “Like” button (❤️) at the beginning or end of the article. This helps others witness the glorious destruction of moral realism.

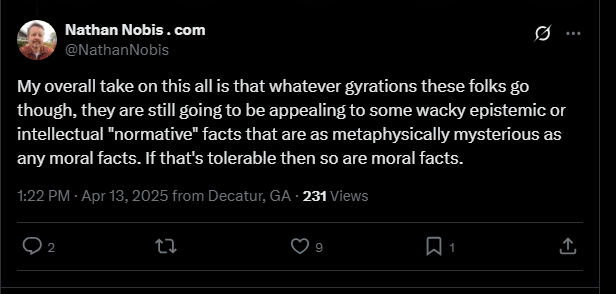

In a recent tweet, Nathan Nobis says the following:

Taken together, we have this remark:

Whenever people try to "argue for" moral anti-realisms they soon enough start talking about what people *should* and shouldn't believe, how people "ought to* reason, and they seem to expect that some people *must* engage what they have to say. Such weird facts they presuppose?!

My overall take on this all is that whatever gyrations these folks go though, they are still going to be appealing to some wacky epistemic or intellectual "normative" facts that are as metaphysically mysterious as any moral facts. If that's tolerable then so are moral facts.

This is weird and obscure for a number of reasons. It’s not quite clear what Nathan is trying to say here.

First, why is “argue for” in quotes? Antirealists are arguing for their position. It isn’t fake arguing. Putting “argue for” in quotes makes it seem like they’re engaged in some kind of pseudoargumentation. This is strange. It’s not like antirealists don’t think that antirealism is true and that one can present arguments for the position. They could hold other views inconsistent with the ability to argue for a view, but I’ve never heard of any with such views.

Second, he highlights that antirealists argue for what people should or shouldn’t believe, how people ought to reason, and that they “seem to expect that some people *must* engage what they have to say.” I’m skeptical that many antirealists adopt the latter view, though it’d be consistent with antirealism to do so. Given that this tweet appeared shortly after I had an exchange with Nathan, he might be referring to me. If so, I never said anything like that, and I doubt antirealists typically go around thinking people “must” engage with them. They may want or expect it, but Nathan may be basing this inference on attitudes or sentiments the antirealists don’t actually have. Keep in mind he says that they seem to expect that some people "*must* engage.” If this is based on supposition, he may simply be mistaken.

Regardless, what makes this especially strange is the remark that follows:

Such weird facts they presuppose?!

This is an odd remark. Nathan’s follow-up tweet elaborates on what he apparently has in mind:

My overall take on this all is that whatever gyrations these folks go though, they are still going to be appealing to some wacky epistemic or intellectual "normative" facts that are as metaphysically mysterious as any moral facts. If that's tolerable then so are moral facts.

Some moral antirealists may very well be appealing to normative epistemic facts that are just as metaphysically mysterious as moral facts. But Nathan isn’t in a position to simply presume that we are doing so. If he wants to know whether any particular antirealist endorses epistemic realism he could simply ask them.

I don’t. I’m a global normative antirealist. I deny that there are any stance-independent normative facts, including epistemic normative facts. Nothing about being an epistemic antirealist would prohibit an antirealist from having a position on what people should or shouldn’t believe, how they ought to reason, or what they must do: these are all first-order, normative epistemic positions. Antirealists simply do not need to presuppose that there are any “metaphysically mysterious” epistemic facts.

I don’t know why Nathan is making these remarks. These are the sorts of remarks I’d expect of someone who has never considered the possibility of epistemic antirealism and is not aware people can be and are antirealists about epistemic normativity as well. Yet Nathan presumably is aware of these possibilities since he’s written extensively about the topic, and even links to some of his own written work in the above tweets.

Let’s have a look at a few of the replies.

Here’s one from Finnegans Take:

First, we’re not trying to get around anything. Finnegan frames this like we have some problem we need to solve. I deny there was ever a problem to solve in the first place. It is realism—both moral and epistemic—that tack on useless, superfluous concepts that don’t solve any actual theoretical or practical problems.

Second, when we provide these kinds of conditional accounts, our point is that there are relational facts about goals and means, and that there are no further, stance-independent facts about what you “should” do, independent of your goals and values. So when we argue with realists, and say that they should be moral or epistemic antirealists, our use of “should” may appeal to a presumptive value that the realist holds, such as a desire for true beliefs.

Contra Finnegan’s Take, this does not entail or even imply that we’d “be okay” with someone responding that they don’t care about the truth (or whatever else the conditional is predicated on, e.g., “if you don’t want to cause unnecessary harm you shouldn’t torture these people.”). Our stance on how to cash out the meaning of normative claims is conceptually independent of our desires about how we want people to respond. In some cases, we might “be okay” with someone saying they don’t care about what’s true. The dispute might be an unimportant one, or we may not be that invested in the conversation. But in other cases, we might not “be okay” with them insisting they don’t care about the value in question. Whether we’re okay with them having different values will depend on our values. This has nothing to do with our analysis of normative claims.

Finnegan’s Take has made the mistake of assuming that if we treat normative terms like “should” as conditionals that only obtain contingent on one having a particular goal or desire, that this entails that if one doesn’t have the desire in question, that we wouldn’t care. Finnegan’s Take seems to think that because some antirealists will say things like “If you want to be kind, then you shouldn’t violently assault other people” that this somehow implies that if someone responds “Well, I don’t want to be kind” that we’d react by saying “Oh well in that case I guess you have no reason to not assault people and I don’t mind if you go ahead and do so.”

Only, our position on the relation between means and ends doesn’t imply anything like this. Finnegan’s Take has simply misunderstood what framing normative claims in conditional terms commits us to and implies about us. It has absolutely no implications at all about how we’re claiming we’d react to someone who didn’t share any particular value. It is entirely consistent with them saying “Well I don’t care about being kind” to react in any way at all, including being outraged and taking active measures to stop them from assaulting anyone. Recognizing that people may have no particular reasons to refrain from doing things we disapprove of does not in any way imply that we don’t care what they do.

Let me give a concrete example of a case where I would be okay and one where I wouldn’t. Suppose I am talking to someone while waiting at the airport. I don’t expect to ever see them again. The following exchange takes place.

Lance: You should accept the evidence I’ve presented that there was never a movie featuring Sinbad as a genie.

Sam: I don’t care about your evidence because I don’t care about having true beliefs, so I’m going to believe there was a movie with Sinbad as a genie.

I don’t care if someone stubbornly adheres to beliefs based on the Mandela effect. So I am okay with this person continuing to believe this. Now suppose I am in this situation:

Sam: Hi Lance. I’m an evil maniac. I am going to toss you into a volcano.

Lance: No, you shouldn’t do that. Assuming you don’t want to harm people or go to prison for murder, that would be a bad idea!

Sam: Actually I want to harm people and don’t care if I go to prison, so none of that is a deterrent to me. I have spent many years reflecting on my values and genuinely don’t care about any of that. I just want to throw people in volcanoes.

In this case, I am not okay with them having values contrary to my own. Note that in this case, it’s true that if they want to not cause unnecessary harm or break the law, then they shouldn’t throw me into a volcano. This is still true. But it completely orthogonal to whether I am “okay” with them not caring about harm or the law. Finnegan continues with this erroneous characterization of antirealists:

The antirealist can and does have preferences about how they want other people to act. I’m an antirealist. I want other people to employ epistemic standards that are conducive towards holding true beliefs. I don’t want to be surrounded by a bunch of insane people who don’t care about what’s true. So I probably wouldn’t take it well in lots of these situations. But Finnegan’s Take says that this suggests that it’s “almost like they think there are commitments you should have no matter what.”

No, it’s not almost like this. This is absurd. Yes, I do think there are commitments you should have “no matter what” (as long as this doesn’t mean “even if I don’t care”). That doesn’t mean I think those commitments are stance-independently true.

Think about things from an antirealist’s perspective: I want the world to be a certain way. I want people to not steal, not kill, to be kind, and so on. I want them to be this way even if they don’t want to be this way. Lots of my preferences are thus preferences about what preferences I want other people to have! So I prefer that people prefer not to steal and lie and kill. I likewise prefer that people employ truth-conductive epistemic practices. This easily explains why I wouldn’t take it well when someone simply doesn’t care about the epistemic or moral standards I care about: because they are acting in ways I disapprove of, that conflict with my goals and values, and undermine the pursuit of my interests. I don’t not take it well because I think there are stance-independent epistemic normative facts. Finnegans Take’s frustration is unwarranted: it’s based on their own lack of imagination and their own failure to adopt an antirealist’s point of view and think about things from their perspective.

But you know what is frustrating? Remarks like this one from Finnegan’s Take. Realists frequently presume that everyone secretly thinks like a realist. They then point to behaviors that are completely consistent with antirealism and in no way indicate some kind of cryptorealist commitment and declare “wow, it looks like they’re acting like a realist,” even when they’re not. That’s frustrating.

And you know what’s also frustrating? That I have made points like this for years and almost no realist ever shows up in my comment section acknowledging that I was right, and that they were being presumptuous and made a silly remark that was misguided and that actually antirealists reacting negatively to people not sharing their norms makes perfect sense and is completely consistent with antirealism and in no way hints at some secret realist commitments. They virtually never do this. They just keep repeating the same canards, over, and over, and over. Antirealism isn’t threatened by inability of realists to think in non-realist terms.

Not all is lost. Travis makes exactly the same point:

This exchange continues:

I completely agree with Travis. If you’re a moral realist, and you become an antirealist, would you just stop caring if someone wanted to kill your family or set you on fire? Why? Why would you only care, or be motivated to act, if there was a stance-independent normative fact that the actions were prohibited? Realists have such a bizarre view, where these obscure facts serve as middlemen for what they are prompted to do, rather than simply moving directly from what they care about to action. But the latter remark is also an odd one:

The problem is that just generally, even outside the moral sphere, we tend to think that being wrong about something objectively licenses certain responses that wouldn't be appropriate in regards to things that are purely subjective. Do you just reject that principle in general?

Who is “we”? I don’t think this, and if Finnegan’s Take things people “tend to think” this well, that’s an empirical question. To my knowledge, there is no empirical research assessing this claim. So I have no idea why someone would be confident it was true. I predict it is not true that people tend to think this.

We also get this in the exchange:

What a bizarre question. What does it even mean to ask why it “should matter” that they’re your values? Your values just are the things that matter to you. Asking why they “should matter” seems to demand some kind of standard of value external to your values, which is precisely the sort of thing Travis is rejecting. It really does seem to me that critics of antirealists seem unable to step outside a realist’s mindset. Finnegan’s take then just repeats the same, tired realist intuition pump:

Think up the most depraved person imaginable and they'll have that relationship to their values. But aren't their values actually bad, in a way yours aren't?

What does “actually” mean here? If it means stance-independently bad, why not say so? And if that’s what Finnegan’s Take is asking, then this is like asking an antirealist “Why not realism, though?” It’s just a pointless, trivial thing to ask. If it means something other than this, well, what does it mean? This strikes me as yet another instance of misleading modifiers.

Unfortunately, Bentham also shows up to agree with Finnegans Take:

As always, Bentham’s takes on moral realism are bad. See here for my most recent critique of Bentham’s remarks on moral realism. We also have Nathan making a remark about what most people think (or in this case, don’t think):

They probably don’t think moral claims have implicit conditionals. On the other hand, they probably also don’t think that moral claims are stance-independently true. Whatever the case may be, facts about what people think fall under the purview of psychology. And yet, for whatever reason, moral realists almost never cite any empirical evidence to support their views. Whether people do or don’t think anything in particular about moral claims is an empirical question best resolved by appealing to the relevant evidence, i.e., empirical evidence. I rarely see any realists present such evidence.

This one is fine, simply noting that there are antirealists about epistemic normativity (as I just pointed out):

Prophet Rob also threw in another remark:

I agree. This is more or less how I think about these matters. Here is the exchange that followed:

Nathan’s response is strange, and once again, I agree with Prophet Rob. It doesn’t make sense to me to ask whether you should do what you want. There are descriptive facts about what you want, and you’ll either do them or you won’t (supposing that’s possible). As Rob says, there is no should. Nathan seems to presuppose that there is a legitimate question about whether you should do what you want. But I simply don’t think there is. I think there are facts about what I want, and there are facts about what would or wouldn’t be conducive to achieving what I want. Normative considerations can be reduced to relations between wants, desires, goals, values, etc., and the means of achieving them. There are no further, irreducibly normative facts.

Critics of antirealism often present strange objections. They routinely seem to believe we are confused cryptorealists, unwittingly appealing to stance-independent normative facts when we make normative claims. Yet they rarely, if ever, present any actual arguments or evidence for such claims. They just sort of…make them. Speculative armchair psychology is not an especially viable way to refute other people’s positions, but if we’re going to engage in armchair psychologizing, I’ll float my own hypothesis: I believe Nathan and others mistakenly imagine that antirealists are secret cryptorealists because they have so thoroughly internalized thinking in realist terms that they struggle to imagine others thinking differently than they do. I hypothesize that they are subject to the typical mind fallacy:

The typical mind fallacy is the mistake of modeling the minds inside other people's brains as exactly the same as your own mind. Humans lack insight into their own minds and what is common among everyone or unusually specific to a few. It can be often hard to see the flaws in the lens, especially when we only have one lens to look through with which to see those flaws.

I am not all that confident this is what’s going on, but I think it’s a possibility. Either way, I don’t intend this as a criticism. However, it’s worth noting that I have had to put considerable work into arguing against the presumption many realists have that moral realism is some kind of default, or “commonsense” position. Realists are often quite insistent that their position is obvious, self-evident, widely held among nonphilosophers, intuitive, and so on. Such claims are often made without qualification and without any apparent distinction between how things seem to them and how they seem to people in general. The distinction appears to simply collapse: they simply assume that the way things seem to them is the way they seem to most (or even all) other people. This kind of sentiment is encouraged by training in analytic philosophy, with its bizarre emphasis on philosophical intuitions. While it would be one thing to insist intuitions are ubiquitous and necessary for philosophy, it is quite another to operate under the presumption that reasonable people would share the same intuitions about any particular case.

For whatever reason, many philosophers have fallen into the habit of treating certain positions as “intuitive,” and others as “counterintuitive,” without regard for the possibility of individual variation. Illusionism is allegedly “counterintuitive.” Moral antirealism is “counterintuitive.” Utilitarianism has “counterintuitive” implications, and so on. This is all quite strange. I never found any of these positions to be counterintuitive, and I endorsed all three not simply because I was persuaded by the arguments, but because they struck me as fairly obvious. This caused no end of grief for me: I was routinely hassled for not having intuitions to the contrary. I have long suspected that philosophers may cultivate manufactured consensus within the field, thereby cementing dogmatism, by driving out people who don’t fall in line and report having the same intuitions. If philosophers discourage people with contrary sentiments like me, this can lead to self-selection effects, i.e., people who think similarly opt-in to becoming philosophers. They will then interact with colleagues who think similarly, reinforcing the misleading impression that “everyone thinks this way” (or at least, everyone that is educated and reasonable). This can then become a self-fulfilling prophecy: if lots of people are told this is what experts think, this can cause people to be drawn towards adopting such views, leading to a self-perpetuating bandwagoning effect rooted in Asch conformity.

I worry that something like this has been going on in analytic philosophy for decades, with disastrous consequences: whatever initial predilections the philosophers who set these forces in motion had, the situation has snowballed, leading to the artificial impression that various positions and ways of doing philosophy are correct when all they actually are is fashionable.

As far as the objections from moral realists: I give them an F. These are very bad objections. Almost all of these objections more or less involve the total failure of imagination on the part of realists, resulting in the mistaken insistence that antirealists secretly endorse moral realism. We don’t, and it’s a sign of a very poor objection that one simply assumes others unwittingly agree with you. It is rarely a compelling move to try to psychologize away one’s opposition. It reminds me of Christians insisting everyone is really a theist and knows God in their hearts, but is in a perpetual state of denial. It’s unfortunate to see so many people convinced everyone simply must think the way they do.

Isn't this basically the Companions in Guilt argument, a la Cuneo? As go moral facts, so go epistemic, hence the anti-realist's argument is self-defeating. But I think epistemic normativity, at least w.r.t. the mundane physical world, can be grounded in my desire (i.e. my stance) to navigate that world in a way promotes pleasure over pain. And I suspect (not that I've worked it out ;-) that that can be extended to more abstract domains. Moral normativity would be grounded in our common (with some exceptions) desire to live in a peaceable, orderly social environment, which to me gestures in the direction of some variety of contractarianism.

And this "If the other guy doesn't care about breaking the law, then he's right to murder me, and I have no valid objections" strikes me as just plain weird. Even if we accept that kind of relativism, my dying violently is against *my* value system, which gives me the right to resist by all means available.

I agree with the thrust of this post, but I suppose in the spirit of candor, one could be more charitable to the realists here and suggest that their objections isn't a failure to imagine the antirealist position, but rather an appeal to an impulse they infer others have. Presumably they believe others to feel a particularly different feeling upon apprehending moral arguments from arguments about descriptive facts.

That's how I understand the discursive argument offered in the initial examples; they're suggesting it's odd to treat moral disagreements with any stridency or strong personal convictions if there's nothing unique about disagreeing on those facts that doesn't apply to disagreements about the effects of gravity.

I understand an antirealist response to this could simply be that people's dispositions vary internally and with respect to each other, and that their dispositions being different for different contexts is an interesting descriptive fact about them, not probative on what properties normative facts have. But I could see how that's less obvious or appealing than "maybe the thing that feels special (to you) is special!"