Subjectivism makes more sense of moral outrage than moral realism

Twitter Tuesday #48

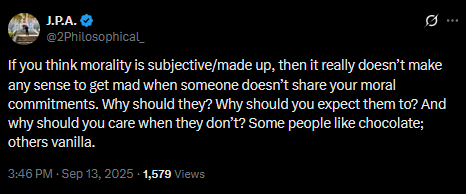

Twitter Tuesday has returned! As always, my goal is to assess remarks made on Twitter. They’re almost always misconceptions about metaethics or bad takes, and this one is no exception. Our most frequent target of criticism, JPA, has once again commented on moral antirealism with the following:

“If you think morality is subjective/made up, then it really doesn’t make any sense to get mad when someone doesn’t share your moral commitments. Why should they? Why should you expect them to? And why should you care when they don’t? Some people like chocolate; others vanilla.”

Let’s assess each of the claims and questions he poses.

(1) “If you think morality is subjective/made up, then it really doesn’t make any sense to get mad when someone doesn’t share your moral commitments”

JPA is mistaken. It does make sense. The reason you’d get mad at someone for not sharing your moral commitments is because that person is exhibiting a disposition to act in ways inconsistent with your goals and values. And since we are all trying to achieve our goals, people who are disposed to thwart those goals are an impediment to our success. If that isn’t a reason for being upset with someone, I don’t know what would be!

Let me start with a nonmoral example. It’s 10,000 BCE. It’s bitter cold and I will die if I cannot find shelter. I come across a large cave. There’s plenty of room for me to stay there. But someone I know and who knows me to be a reasonable person is already occupying the cave, and they refuse to let me in, insisting it’s “their cave”. I have two options: stay outside and die, or try to force my way in. Violent conflict ensues. In this situation, would it be reasonable or make sense to be angry with the person who refuses to let you in? I think so. And yet do you disagree on literally any facts at all? No, you don’t. Conflicts often arise as a result of conflicting goals, not as a result of conflicting beliefs. Indeed, conflicting beliefs alone make little sense as a basis for conflict or anger unless, and only unless, those beliefs had something to do with your goals! After all, if you and another person disagree on what the facts are, but neither of you cares what the consequences of those differences in belief are, how could you possibly have any conflict?

In short, not only does it make sense for a subjectivist to be mad at someone for not sharing their moral values, the subjectivist has a direct path from their moral standards to being angry with others that makes perfect sense: their moral values are tightly bound to and largely (if not entirely) constituted by their goals (at least their moral goals), and as such anyone who is disposed to act in ways inconsistent with those goals is thwarting the subjectivist’s aims.

In contrast, why would a moral realist get mad at someone who didn’t share their moral values? Consider a moral realist who believes it is true that abortion is morally wrong. They encounter a pro-choice activist who believes abortion is morally permissible. Despite their belief that moral realism is true and that abortion is morally wrong, they don’t especially care to stop anyone from getting an abortion and have no emotional investment in preventing abortions at all. It would make no sense for this person to be angry at someone who is in favor of abortion. Of course, I’ve simply stipulated an imaginary realist who doesn’t care. So what would it take for a moral realist who is against abortion to be angry at someone who is pro-choice? The mere belief that abortion is morally wrong clearly isn’t enough. They have to care. In other words, they have to have some desire, goal, or motivation to oppose the pro-choice stance…just like the subjectivist.

The belief that it’s stance-independently wrong to get an abortion does no direct motivational work at all. Such a belief is practically inert unless, and only unless, it is paired with some goal or desire to prevent abortions, an attitude of opposition to people who hold contrary moral commitments, and so on: precisely the psychological profile already present in the subjectivist. We can trace the path from moral stance to anger for each as follows:

Subjectivist

Has the desire that abortion rates be lower → Anger at someone who is disposed to act in ways that would increase abortion rates.

Realist

Believes it is stance-independently wrong to get an abortion → Has the desire to comply with this moral rule and thus has a desire that abortion rates be lower → Anger at someone who is disposed to act in ways that are inconsistent with the stance-independent moral facts, including acting in ways that would increase abortion rates.

The realist has no explanatory advantage for making sense of anger at someone who lacks one’s own moral commitments because their own attitudinal and behavioral profile is subordinate to and must include virtually identical features as the subjectivist, anyway, and it is precisely those features that do all the heavy explanatory lifting. The realist simply includes explanatorily superfluous additional steps.

And yet somehow JPA thinks the subjectivist’s response makes no sense. If anything makes no sense, it’s JPA’s remark. And this isn’t even getting into additional questions one might have about the realist’s dispositional profile above. It makes sense to act on my goals and values. And one could simply have a brute goal to comply with whatever the stance-independent moral facts are. But, personally, I am both flabbered and gasted by this: why comply with the stance-independent moral facts? Why care? Sure, I grant, you could simply care, and no further argument or justification is needed. But if that’s what a realist wants to go with, then how are they in any better of a position than the subjectivist?

This isn’t the typical response I get from realists, though. Typically I get worse responses. One common response is to play around with words and insist that it makes no sense to ask why one should comply with the stance-independent moral facts, due to the simple fact that these moral facts are, by definition, the set of facts you should comply with. Why do I say this is playing around with words? Because the realist is playing, perhaps unwittingly (though some realists may be maliciously self-aware of how much shit they’re full of, who knows), they’re playing around with presumptuous tautological phrasing loops. Here’s how the con works. The realist insists on interpreting what the antirealist is asking within a closed loop of consistently defined terms. So when the realist asks why comply with the stance-independent moral facts this is interpreted as asking the question:

“Why should you comply with the stance-independent moral facts?”

I’ve bolded the key term here. The realist interprets “should” in this question in terms of the realist’s analysis of the semantics of normative language. And they, of course, do the same for their conception of realism itself: for the realist, the stance-independent moral facts are that set of facts that, by stipulation, you should comply with. So asking why you should comply with the set of facts you should comply with is a confused and silly question. Checkmate, antirealist. The antirealist has been shown to be a dupe and an idiot who can’t even ask a reasonable question.

But this is not what the antirealist is asking. The antirealist is not trying to employ the realist’s realist terminology. They’re asking a different kind of question. Realists can try to be as nitpicky and pedantic as they want to avoid answering this question, and in my experience I’ve seen them thrash like a badger in a beehive to simply not directly answer the damn question. But the antirealist is asking something like this:

Do you care to comply with these stance-independent moral facts? If so, why? Is it a goal that you have? Are you motivated to comply with the stance-independent moral facts, whatever they may be? If so, why? Why do you care? Why does this matter to you?

What is the point in asking these questions? It is to illustrate something simple and unavoidable: that all action is mediated through the goals and desires of the agent, including acting in accord with the stance-independent moral facts. Moral realism, were it true, would still be utterly subordinate to whether any of us preferred to comply with it. And if one doesn’t, all the “oomph,” “authority,” “clout,” or “force” that realism supposedly has is exposed as the gossamer wishes of intellectuals and nothing more. I have never seen a decent rejoinder to this concern anywhere. If you know of one, in an academic source or otherwise, share it in the comments below or shoot me an email.

Subjectivism makes at least as much sense of moral outrage as moral realism. Perhaps more, because it cuts out the middleman. Whereas the realist has to account for both moral beliefs that are not reducible to the agent’s own goals and desires and (if the realist is an externalist) are not necessarily motivating, as well as the disposition to comply with those beliefs, the subjectivist can move straight from one’s values more or less constituting or being closely connected to one’s goals and desires to one’s reactive attitudes. The realist has all these superfluous steps that, even if they could account for them, still require accounting for more or less all the same things the subjectivist has to account for.

So on what basis does JPA think that it makes no sense for a subjectivist to get mad at others? What I find strange about this remark is that JPA never makes clear what his reasoning is. Why does he think it doesn’t make sense? I wish he’d explain what his reasoning is somewhere, because absent a rationale for the remark he leaves us with little to critique (or be persuaded by).

(2) “Why should they?”

What is this even asking? First, a subjectivist could just think “I don’t think it’s the case that they should.” This is consistent with being mad at them. You can be mad at people for acting against your preferences simply because they’re acting against your preferences. No further reason is needed. If I want someone to get out of my way and they won’t, that’s going to frustrate me. If I am dying of thirst and someone has a big jug of water they don’t need and they refuse to share out of spite or whimsy, I’m going to be mad at them. Wouldn’t you? Before we even bring morality into the question, it is trivial to make a simple point: we can and do get mad at people when they act in ways that thwart our interests. We can simply extend this same reasoning to moral concerns.

Second, on some antirealist analyses to say they “should” just is to say one has a preference that they do so. So there is a trivial sense in which they “should”: if “should” just means I prefer that someone do a particular thing, then asking “Why should they?” doesn’t make much sense. I have a preference that they do a certain thing. What, exactly, does it even mean to ask a subjectivist if they “should” do what I prefer they do? That’d be a bit like asking if I want them to act in accord with my preferences about how they act: of course I do! Ironically, this is an exact reversal of the response realists (often smugly) give to antirealists who ask why they should comply with the stance-independent moral facts, i.e., that the stance-independent moral facts are, by definition, the set of facts you should comply with. Well, if me saying someone should give me a jug of water just is to say I’d prefer that they do so, then it makes no sense to ask “Why should they?” If your should is indexed to my standards, they should by definition. If it isn’t, then which standard are you indexing it to? Because if it isn’t my standard, then I’m not, as a subjectivist, committed to thinking they should.

Some realists like to play these semantic games when it works in their favor, so they should appreciate that the same game can be played when it doesn’t work in their favor. Unfortunately, there are almost never any able defenders of subjectivism to point out the hypocrisy, double standards, and generally lopsided and lazy arguments against subjectivism that realists direct at it. If it makes no sense for me to ask why I should comply with the stance-independent moral facts on a realist’s semantics, it likewise makes no sense to ask a subjectivist why anyone should comply with their moral values.

If JPA instead has in mind some realist notion of “should”, an antirealist isn’t going to think they “should” in a realist sense. A subjectivist prefers people act a certain way. They don’t think that people “should” act in any particular way in any other respect than this. If JPA wants to claim that subjectivists act like people “should” share their preferences in a way that is inconsistent with subjectivism, two points: first, this would be a reason for charging that specific subjectivist with acting in a way inconsistent with their commitments; it would not in itself be an objection to subjectivism. Second, it’s an open question whether any particular subjectivist actually does act in such a way. JPA may (and I think typically does in practice) mistakenly infer that subjectivists/antirealists think and act in ways inconsistent with their metaethical views. But I don’t think he’s done much of anything to actually show this is true.

To take stock of what I’ve shown here: JPA’s question is ambiguous with respect to what’s meant by “should.” If we resolve the ambiguity in terms of the subjectivist’s own semantics, JPA’s question is confused and makes no sense. If we resolve it in favor of a realist’s semantics, then the subjectivist is completely off the hook: they can simply point out that since they don’t think anyone “should” do anything in the sense realists think they should, that they don’t think anyone “should” comply with their moral standards in the realist’s sense. At this point, it would make no sense to say “So how can you think or act like they should?” Simple: because the subjectivist thinks and acts like they should on the subjectivist analysis of the semantics of “should,” not the realist’s.

Any realist who cannot understand this is guilty of the halfway fallacy: i.e., mistakenly thinking that the subjectivist must be simultaneously committed to subjectivism as a philosophical position but also operate within a non-subjectivist semantic framework, committing them to a confused, internal contradiction. But subjectivists aren’t committed to half of subjectivism; subjectivism historically is both a metaphysical position on the status of moral claims and a semantic position on the meaning of moral claims. It’s a package deal. Criticizing the subjectivist by surreptitiously ignoring half the position and smuggling in your own preconceptions only reveals how bad of a philosopher you are, not how indefensible subjectivism is.

What’s especially unfortunate about JPA’s question is that it is both ambiguous and a loaded question. The question seems to imply the subjectivist thinks they “should.” But the subjectivist isn’t obligated to think they should. Philosophers of all people should know better than to ask ambiguous and loaded questions.

(3) “Why should you expect them to?”

Subjectivists don’t have to expect them to and you don’t have to expect anyone to share your moral commitments in order for it to make sense to be mad at them when they don’t. I don’t expect terrorists to share my moral standards. Does this mean I can’t be mad at them if they commit acts of terrorism? No.

(4) “And why should you care when they don’t?”

I prefer to not be robbed. Why should I care if someone wants to rob me? …Because I don’t want to be robbed. Has this possibility not occurred to JPA? Does he think this an unsatisfactory response? If so, why?

Suppose moral antirealism is true. Would JPA be indifferent if someone wanted to rob him? If not, then he can answer this question himself. If he would care then ask yourself whether you really find moral realism to be intuitive if one of the implications of it is that, if realism isn’t true then it would make no sense for you to care if someone robbed you, or set you on fire, or wanted to murder your family. That’s the intuitive position? That “I don’t want to be set on fire” isn’t a good enough reason to care if someone tried to set you on fire and to be mad at them if they did? Maybe moral realists need to get their antennae checked.

What is unsatisfactory about me not wanting to be robbed or set on fire or have my family murdered entirely on the basis of the fact that I don’t want any of these things to happen? Are moral realists so out of touch with reality that this doesn’t immediately strike them as a fully satisfactory response? And if it is a satisfactory response, what is the point of these questions? Because all of these questions give, to me, the impression that they are rhetorical, and that the subjectivist has no reasonable response because their position is stupid and makes no sense. Only it does make sense. In fact, as I think I’ve shown, it barely takes any effort to show that it makes sense.

(5) “Some people like chocolate; others vanilla.”

And some people prefer other people to act a certain way even if they don’t. And they get mad at those people when they don’t act in the way that person wants. JPA reiterates the common and misleading trope of comparing moral preferences to taste preferences. Since the latter only typically concern an interest in one’s own conduct and experience, the implication is that moral preferences, if they are to be preferences, should share these features in common. This is a mistake. One can have preferences about how other people act, especially when those actions can impact you. Someone eating chocolate ice cream is probably not going to interfere with my goals or harm me. Someone wanting to set me on fire would. As such, while I have no preference for what ice cream flavor others choose, I do have a preference that people not set me on fire. In fact, I’d prefer that nobody be set on fire. I wouldn’t want to live in a world where people can set people on fire. So I’d prefer we agree to prohibit such actions and punish people that do so. Is there anything even remotely mysterious about this? Is it at all hard to understand why I don’t care what ice cream flavor people prefer, but I do care that they don’t go around setting each other on fire?

Simply put, moral preferences often differ in scope from taste preferences: moral preferences often concern how everyone acts, while taste preferences often concern only how you yourself act.

When critics of relativism/subjectivism criticize it, they often commit the overcomparison fallacy. The overcomparison fallacy occurs whenever you mistakenly infer that two things that are being compared with respect to one or more dimensions are also being compared with respect to other dimensions. In the case of preferences, the only relevant comparison between moral preferences and taste preferences is that both consist of attitudes or desires about what occurs in the world: how you yourself will act, what events take place, what outcomes are realized, and so on. Having a moral preference does not require that the preference be narrowly concerned with your own conduct but not anyone else’s. When JPA and others provide taste preferences as examples, whether they intend to or not, they mislead their audiences. They mislead them because taste preferences are:

Typically not that important.

Not something we have higher-order preferences about. I wouldn’t care much if my ice cream preferences changed (though I’d care if they changed to a rare or expensive flavor). I care a lot more that my moral values don’t change.

Typically narrow in scope (they only apply to oneself) rather than universal in scope (applying to everyone).

These differences can give the impression that moral preferences exhibit these characteristics even if that isn’t the intent of the person making this comparison. So the subjectivist is made out to be some kind of confused idiot who on the one hand claims to have unimportant, narrow preferences against robbing and murder, but on the other hand seems to care a lot, treating them as important and broad in scope. Hence the notion that the subjectivist is engaged in some kind of confused performative contradiction. Only the subjectivist is not engaged in any performative contradiction. JPA and others are, I suspect, simply failing to appreciate that not all preferences exhibit features (a), (b) and (c). They can just…not have those features.

Conclusion

I want to conclude with a harsh remark. JPA’s objections to subjectivism, and moral antirealism in general, are not simply terrible. They are so lazily and easily rebutted that I’d be disappointed if they came from an undergraduate. I don’t say this because I want to antagonize JPA. I don’t think JPA cares at all about my perspective. Rather, I think JPA’s penchant for blocking and disengaging with critics has left him in an intellectual bubble of his own making. I think this has insulated him against encounters with people who would at the very least prompt him to recognize that the views he criticizes have more going for them than he appreciates. My hope is that JPA will consider my several invitations for a discussion and come have a conversation with me. Let this serve as yet another invitation: JPA, you are welcome to join me for a conversation about moral realism! I believe my conversations with David Enoch, Mike Huemer, and others show that while I may be harsh on a person’s views (especially in writing), it takes no effort on my part to be kind and respectful towards my interlocutors.

As an added indication of the relevance of such a conversation, I watched all of JPA’s recent conversation with Spencer Case, which you can find here:

JPA asked about whether experimental philosophy has had anything to say on the matter of whether nonphilosophers are realists. Spencer had little to say on the matter, and understandably so; this isn’t Spencer’s area of specialization. But it is mine. I wrote my dissertation on the topic (you can find a shorter preliminary paper written with my excellent friend and coauthor, David Moss, here), and JPA may be surprised to find that I found myself largely in agreement with Spencer. I don’t think we have any sort of definitive evidence that nonphilosophers tend to be moral realists or antirealists. In fact, I’ve been critical of the research that reports such findings (though to be fair I’ve been more critical of findings reporting most people are realists; this has more to do with the methods of these studies, though, rather than the results).

I also agree with Spencer that prompting people with a certain line of questioning probably would reveal a tendency towards giving a realist response. However, where Spencer and I probably disagree is that I think that an equally legitimate line of questioning would reveal antirealist responses. I don’t think either pattern reveals people tend to favor realism or antirealism on reflection. I think endorsing one or the other views comes downstream of such a vast host of considerations that I don’t think there is any simple answer as to what people would tend to favor on reflection. I think the answer is that what people will favor will be contingent on a host of background considerations of such potential variation that there is no canonical, uniform, post-reflective position most people would favor. If JPA is interested in this research I’d be happy to talk about it.

I never knew until I started reading your blog that metaethics was a blood sport ;-).

Regarding your specific request of someone dealing with your question of why we should care in the literature here is a quote:

"We want something more, and something more human. #is is

Korsgaard’s central issue with realism. Traditional realism, she argues, leaves

an explanatory gap: the existence of robust, mind- independent normative

facts doesn’t explain why these things count as reasons for us. It’s just as

though ‘we have normative concepts because we’ve spotted some normative

entities, as it were wafting by’ (1996, 44)."

This is from

Christa Peterson and Jack Samuel, The Right and the Wren In: Oxford Studies in Agency and Responsibility. Volume 7. Edited by: David Shoemaker, Oxford University Press. © Christa Peterson and Jack Samuel 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192844644.003.0001

The citation for Korsgaard is "Korsgaard, Christine, ed. 1996. #e Sources of Normativity. Cambridge University Press."

As I understand Peterson and Samuel's answer in the essay, they take it that we have reason for morality (in terms of compassion) because linguistic competence consists in being able to imagine another person's state of mind. So if we imagine another person's pain we do so in a way such that we experience that pain including aversion to that pain that is the desire to alleviate that pain becomes present when we understand (linguistically) that another person is in pain.

One can disagree that linguistic competence works like that. Another thing you can deny is that it would lead to a sufficiently general convergence of different agents on how to behave.

To use your example, if I travel through the cold I come upon the cave. The occupant of the cave as in your example tries to drive me off. However let's say there is not just one person but a bunch of people, the man's family in the cave. In my interaction I realize that the reason the guy doesn't want me in there is there is not enough room, he needs to make sure his children have a place by the fire. I empathize with the children and so gain the desire that they not be denied heat also and this if it does not remove my desire to enter the cave at least mitigates it and makes me less angry about the refusal. Likewise my remonstrating with the cave occupant might elicit sympathy from them that changes there desire to converge with mine to be in the cave and we might work out an accommodation without violence etc.

Obviously we do experience compassion for others as a motive. Whether it arises from our linguistic ability (or broader ability to communicate with and understand each other) seems like an open question. Another open question is would everyone be so moved and so moved so as to converge to the same judgement, if they were free of practical constraints on debate (freezing to death forecloses debate early in this case) and so on. If not then this is perfectly in line with subjectivism, some individuals (having one set of particular subjective views) will after communication converge on a set of moral practices, others (other subjective perspectives) will just disagree and not converge upon honest discussion. If however all rational beings capable of the use of language would converge on the same collective attitude (who should be let in the cave, for how long etc.) or even if all human beings, that to me sounds like a moral fact that is if not universal at least sufficiently general as to constitute the kind of thing posited by moral realism.

Note I take it realism is about a) something being the case (something being real) and b) this being somehow accessible to us human beings (something about our reasoning or perception allowing us to reliably converge on beliefs conforming to that situation). For example scientific realists don't think there are just mind independent (stance independent) facts about scientific posts like electrons and then independently of this we have beliefs about electrons, it's precisely that we have reason to think our beliefs about electrons have been formed, altered etc. so as to converge on these independent facts. Whereas scientific antirealists don't need to think there are no facts about electrons (that would be sufficient but not necessary to be a scientific antirealist), they just need to deny that actual human beings have reason to think their actual scientific beliefs have somehow converged on these facts.

I'm not really convinced by Peterson and Samuel's kind of argument, but it is to me at least a little suggestive and tries to address the worry about moral realism not itself being motivating.