You can just care about things

Twitter Tuesday #50

1.0 People are wrong on Twitter

This may be news to you, but people say a lot of things on Twitter that aren’t true. Since I decided to make criticizing the lazy, thoughtless dogmas around the moral realism vs. antirealism dispute my personal crusade, I’ve remained vigilant against misunderstandings and errors related to metaethics. This marks my 50th entry in this series. I don’t plan to quit. If I have to make an example of the unending misunderstandings and mischaracterizations of moral antirealism with a thousand posts documenting the same nonsense, I will. There is no excuse for how badly philosophers and laypeople alike have managed to botch their handling of moral antirealism.

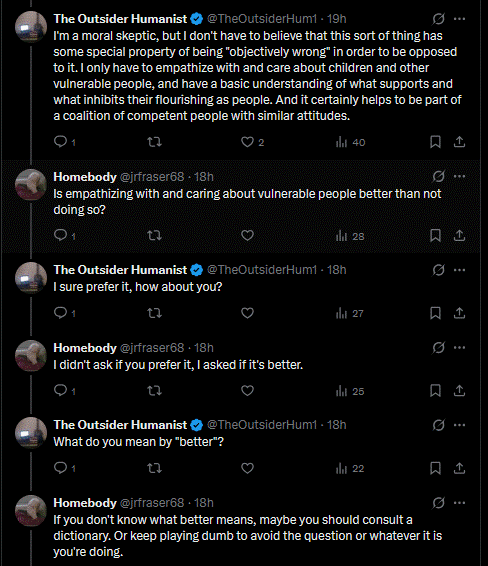

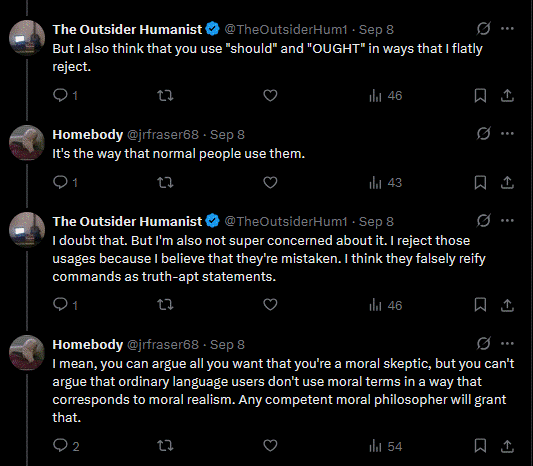

Here we have an extended exchange between somebody going by the name Homebody and someone called The Outsider Humanist, whose posts I have seen on occasion. You can see the start of the discussion here.

If you want to see a general template for how I approach these tweets, see Bentham’s Bulldog’s parody, which is an uncannily accurate characterization of the recurring themes in my critiques. Incidentally, I am also mentioned towards the end of this lengthy exchange. Perhaps I’m having some impact. I really hope I don’t have to write 1000 posts for people to stop making the same mistakes.

2.0 You don’t know what [word] means?!

Homebody begins with a practice I’ve seen people employ in many debates: When The Outsider Humanist asks Homebody what they mean by “better,” Homebody replies:

If you don’t know what better means, maybe you should consult a dictionary. Or keep playing dumb to avoid the question or whatever it is you’re doing.

One of the most annoying moves in the online debate world is the “if you don’t know what [term] means…” response. Here’s how it works. One person will make a particular claim that uses one or more terms. A second person will respond asking for clarification about one of the terms. Why might they do this? It’s possible that they are a sophist who wants to tangle the other person up in an endless web of pedantry. But there’s a far more innocent possibility: they want to understand what the other person means.

The Outsider Humanist is not some illiterate troglodyte asking what the word itself means. They’re asking Homebody what Homebody means. In case this is news to Homebody, not everyone means exactly the same when they use particular terms, especially in a philosophical context. Words don’t have a single meaning forged into the fundament by Hephaestus. Words are polysemous and their meanings shade and vary along different dimensions. Our terms in various situations have distinct meanings, or carry distinct pragmatic connotations in their contexts of usage, or their meaning is obscure, or their meaning is underwritten by one or more presuppositions held by the speaker. This is especially true in philosophical disputes, since terms are often loaded with that person’s presuppositions or theoretical positions, so it’s important to be clear about what that person takes those terms to mean.

When someone asks you what you mean, unless there is a very good reason to think they’re filibustering or trying to pull off some sort of linguistic legerdemain, here’s what I suggest: just answer them. What that person is typically trying to do is understand what you’re talking about. The specific words you use aren’t as important as what you mean by whatever words you use. The person is not trying to understand the words, isolated from any context or use or person using them. They’re trying to understand you. Sure enough, look at what The Outsider Humanist says next:

I didn’t ask what better means or what the dictionary says. I asked what *you* mean. But I won’t play dumb.

I think that “better,” when used on its own without a “for” attached, is a word that we use to express our preferences for one thing over another, along with belief or hope that others will share those preferences.

If that’s not what you mean by “better,” then what do you mean by it?

If you respond to someone’s request to clarify what you mean as an opportunity to ridicule them by suggesting they’re a moron who doesn’t understand English, you should reevaluate how you engage with others. And if you sincerely think that a person asking you for clarification is asking you for basic dictionary definitions, then maybe you should just provide one. The irony here is that people who say things like “You don’t know what [word] means?” are implying that the other person is being foolish when it is more foolish to sincerely think the person doesn’t know what the word means or to fail to appreciate they’re asking you what you mean, and are not asking for a basic dictionary definition.

We need better dialectical norms, and those norms need to be enforced. The “you don’t know what [word] means?” and its variants are top-tier forms of poor debate conduct (or simply incompetence) and people should call it out when they see it.

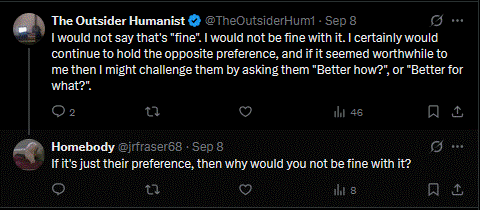

3.0 Ignoring Appraiser Relativism

The Outsider Humanist turned the question back on Homebody as you saw above, again asking Homebody what they mean by better. Did they answer? Of course not. Instead, they try to keep the ball in The Outsider Humanist’s court the entire time:

So if someone said it was better to not care about vulnerable people, that’s just fine because it’s their preference, yeah?

Homebody attempts to do what many critics of relativistic positions do: presume the person endorses agent relativism, then try to make it seem like that person must think that if someone else is okay with torture or whatever, that they (the relativist) must be okay with it. This is what Homebody does, and it reveals a straightforward misunderstanding of what The Outsider Humanist said. Recall that they said:

I think that “better,” when used on its own without a “for” attached, is a word that we use to express our preferences for one thing over another, along with belief or hope that others will share those preferences.

This is closer to appraiser relativism. If The Outsider Humanist says “Empathizing and caring about vulnerable people is better than not doing so” this would presumably mean something like:

I prefer that we empathize with and care about vulnerable people and hope others share this preference.

If someone else thinks it’s not better to do so, does it follow that “that’s just fine because it’s their preference”? No. This question doesn’t even make sense. Fine relative to what standard (i.e., what standard of preferences)? Obviously, it’s not fine relative to The Outsider Humanist’s preferences; they just said it’s not. And just as obviously it is fine relative to whoever does not think it’s better to empathize with and care about vulnerable people. What we have are two different sets of preferences. The Outsider Humanist is under no obligation to think that because someone else has a different set of moral standards that it’s “just fine” for them to have different preferences. Homebody has simply misunderstood The Outsider Humanist. They ably handle this in their own response, only to be met with a common question people pose to antirealists that continues to strike me as very strange:

If it’s just their preference, then why would you not be fine with it?

Note the use of the misleading modifier “just” their preference. I wouldn’t say it’s “just” a preference if someone preferred to kill me and my family. Preferences can be and often are significant. For whatever reason, critics of antirealists and relativists in particular, keep overcomparing the antirealist/relativist’s characterizations of moral standards as preferences with trivial and mundane preferences like a preference for ice cream. In other words, they seem to think that if moral values and taste preferences are both “preferences,” that the former inherit all the characteristics of the latter, including their lack of significance and limited scope. This simply isn’t true.

Not all preferences are trivial or mundane. I prefer my family over other people’s families. So much so that I would go to great lengths to rescue my family, but would not do so for other people’s families. Imagine how asinine and goofy it would sound to encounter the following exchange between a Normative Family Realist and a Normative Family Antirealist:

Realist: So you don’t think your spouse and children are objectively more important than other people’s spouses and children?

Antirealist: No, that’s absurd. That I prefer them is a fact about my psychology and my subjective values. I don’t think they’re intrinsically more important than other people’s families in a way other people would be obligated to recognize. I prefer my family, and they prefer their families.

Realist: So then why do you care more about your family than other people’s families?

Antirealist: …I simply do.

Realist: What’s your justification for preferring your family over other families?

Antirealist: My what? Why would I need a justification?

Realist: Of course you need one! What are you, an anti-intellectual? If you can’t provide a rational justification for preferring your family over other people’s families, then you’re not justified in prioritizing your own family. Let me put it this way: Suppose another family thought it was morally acceptable to murder your family and attempted to do so. Would you allow them to do so?

Antirealist: No…because I prefer they don’t murder my family. It wouldn’t be fine by my standards.

Realist: But it’s just their preference that they kill you and your family in order to survive, so why wouldn’t you be fine with it?

Antirealist: Because it would go against my preferences, and I act and judge on the basis of my own preferences, not theirs.

Realist: But your preferences aren’t any more valid or correct than theirs.

Antirealist: Not objectively, no. So what?

Realist: So then why do you care to act on your preferences?

Antirealist: Because my preferences just are the set of things I care about and that motivate me to act. What the hell else would motivate you to do anything?

I’ve had many exchanges similar to this with realists. They have this bizarre notion that you can’t just care about things. That there have to be truths about what things ought to be cared about independent of whether you care about them, and then you’re supposed to figure out what those truths are and comply, caring about the things that have the to-be-cared-aboutness property. It’s bizarre, and yet they claim their position is intuitive and antirealism isn’t. Something has gone seriously wrong with their intuitions. I’m not saying all realists think this way, but it’s a common occurrence. It’s also common to just hit a brick wall with people who seem incapable or unwilling to construe antirealism or relativism as anything other than some form of crude agent relativism.

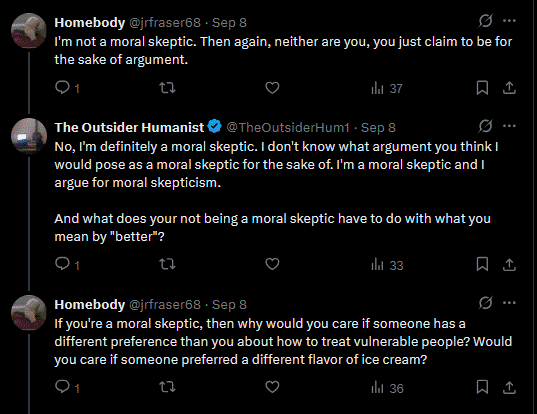

So, if something was just someone’s preference, why would I not be fine with it? Well, it depends on the preference. If them acting on the preference is at odds with achieving my goals, then of course I am going to care. Just suppose moral realism is not true. Would you just not care if someone decided to kill you?

Incidentally, I wrote all of this before I even got to this part of the exchange:

The first couple of posts are a bit odd. Perhaps Homebody thought Outsider was just defending skepticism for the sake of argument. But I have encountered people who try to insist I don’t believe what I say I do, as if I am pretending or self-deceived. It’s obnoxious for people to do this, and I hope that isn’t what Homebody is doing here. But the latter part exhibits precisely the mistake I am talking about:

If you’re a moral skeptic, then why would you care if someone has a different preference than you about how to treat vulnerable people? Would you care if someone preferred a different flavor of ice cream?

This is ridiculous. Suppose you were standing at a bus stop late at night next to a stranger who also appeared to be waiting for the bus. Now suppose they say one of the following two things:

Ice Cream Man: “Where are you headed? I’m off to pick up some ice cream for my wife. She always wants weird flavors, like Earl Grey or watermelon mint, so I gotta go to Thermopylae (a local ice cream place that features 300 flavors). I just prefer chocolate.”

Skin Lamp Man: “Where are you headed? You know what it doesn’t matter. I’m an insane serial killer and I am going to take you home in a suitcase and turn you into a skin lamp. I really prefer my lamps to be made of human flesh.”

Now let me pose this question to you:

If you’re a skeptic, why would you care if someone has a different preference than you? Would you care if someone preferred a different flavor of ice cream?

It’s easy for a skeptic to say no to this. But now let’s ask a slightly different question:

If you’re a skeptic, why would you care if someone has a different preference than you? Would you care if someone preferred to murder you and use your flesh to create lampshades?

It’s just as easy for a skeptic to say “yes” to this. What would you say? After all, it’s just a preference, right? Why care?

What Homebody and other critics of antirealism/relativism fail to appreciate is that we can care about some preferences others have and not care about others. And we can have preferences that don’t concern what others do and we can have preferences that do concern what others do. Not all preferences are as mundane as taste preferences. Not all preferences are preferences merely about our own conduct. We can and we do have preferences about other people’s conduct. I prefer peanut butter ice cream. I don’t care what ice cream flavor you like. But I do care that everyone else not indiscriminately kill people.

This isn’t that complicated or nuanced or mysterious of an insight, so why do critics keep bringing up these same stupid objections? These objections are so bad, so lazy, and so thoughtless, they’re the kinds of inane remarks you’d expect in a sketch comedy or a comic strip. How do they survive in the wild? If everyone read my responses to this nonsense, would they stop doing it? I doubt it. I suspect many critics would be dismissive, or insult me, or ignore me, or quickly forget what I’ve said, and go right back to this. I see it repeatedly, so much so I have this incredibly repetitive blog where I keep bringing up these same points. Maybe I do need to go on Twitter and just keep engaging with people who say these things? I don’t know. What do you think? I really hate the thought of going on there.

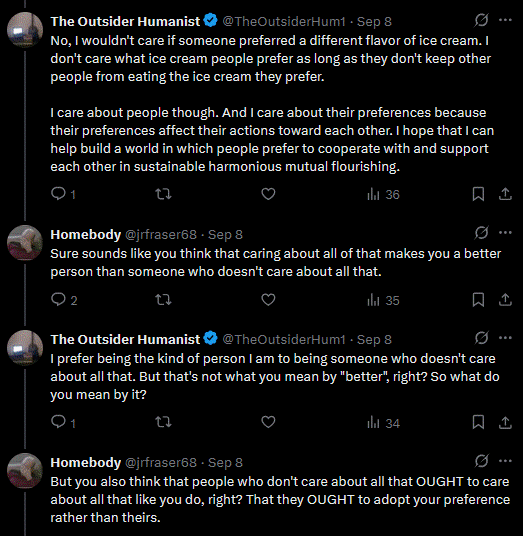

In any case, The Outsider Humanist continues to present excellent responses:

Good lord. The attempts to dredge up some sort of objection just keep coming. Alright. Whatever. Let’s address this, too:

Sure sounds like you think that caring about all of that makes you a better person than someone who doesn’t care about all that.

Is this supposed to be a gotcha? Of course a skeptic can think that caring about things makes them a better person than someone who doesn’t care about the same things…relative to their own standards. For instance, I like progressive metal. I think my taste in music is better than people who like Drake, because Drake’s music is the worst. But I do not think my taste preferences are stance-independently better or that Drake’s music is stance-independently the worst. I am simply speaking about my own preferences. Nothing about doing so prohibits one from judging others relative to one’s own preferences, and doing so in no way bars us from making evaluations of what’s better or worse.

Are you a realist about what food is good or bad? If not, do you think it would make no sense to say that some restaurants are better than others? Must you think that a restaurant could only be better than another if it was better independent of anyone’s taste preferences, including your own?

But you also think that people who don’t care about all that OUGHT to care about all that like you do, right? That they OUGHT to adopt your preference rather than theirs.

If “ought” claims are construed relative to one’s own preferences, then this would be a bit like asking someone:

“Given that you prefer that people care about X, do you prefer that people who don’t care about X care about X?” to which the answer is a trivial “Yes.” Oughts are to be understood as claims relativized to the preferences of the person making the normative evaluation, so of course if you prefer other people share a given value then you think they “ought” to, since this is just another way of saying the same thing.

What troubles me about questions like this is that it’s as if the person raising these questions can’t get outside of their own mind and can’t analyze things from the perspective of the skeptic/antirealist/relativist. It’s as if they think the skeptic/antirealist/relativist simply must think that people “ought” to do things in some non-antirealist way.

4.0 Presumptions about ordinary moral language

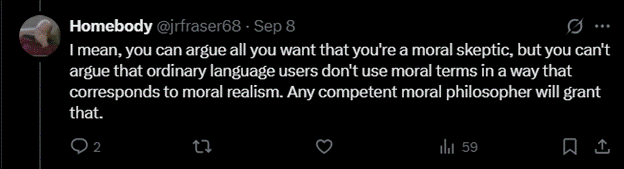

Note that Homebody continues to ignore repeated requests to offer their own account of the relevant concepts. I’ll skip over some of the conversation that follows and proceed to this exchange:

We’re almost to the part where they mention me, but let’s pause a moment to consider this interaction. The Outsider Humanist repeatedly asked Homebody what they meant, which they ignored. Outsider politely let this slide and kept responding, right until they get to this point. After stating that they reject the ways they think Homebody uses terms like “should” and “ought” Homebody states that:

It’s the way normal people use them.

As we quickly discover, this way is the realist way:

I mean, you can argue all you want that you’re a moral skeptic, but you can’t argue that ordinary language users don’t use moral terms in a way that corresponds to moral realism. Any competent moral philosopher will grant that.

Of course you can argue this. What a bizarre claim to make. That ordinary people use moral claims in a way that best fits with moral realism is not something realists have ever convincingly established. Then we have this presumptuous remark that “Any competent moral philosopher will grant that.” Many of the most prominent metaethicists throughout the 20th century rejected this claim, as do several contemporary philosophers. Aside from moral realists and error theorists, many competent moral philosophers have explicitly argued that ordinary moral language best fits with various nonrealist analyses, including A.J. Ayer, R.M. Hare, and more recently Don Loeb and Michael Gill, all excellent philosophers. And they aren’t the only ones. Take, for instance, this paper from Nils Franzén. Here’s the abstract:

Within contemporary metaethics, it is widely held that there is a “presumption of realism” in moral thought and discourse. Anti-realist views, like error theory and expressivism, may have certain theoretical considerations speaking in their favor, but our pretheoretical stance with respect to morality clearly favors objectivist metaethical views. This article argues against this widely held view. It does so by drawing from recent discussions about so-called “subjective attitude verbs” in linguistics and philosophy of language. Unlike pretheoretically objective predicates (e.g., “is made of wood”, “is 185 cm tall”), moral predicates embed felicitously under subjective attitude verbs like the English “find” [...]

Homebody is welcome to insist all these people must be incompetent. If so, good luck making the case for that. Take, for instance, these remarks:

[...] in every case in which one would commonly be said to be making an ethical judgment, the function of the relevant ethical word is purely ‘emotive’. (Ayer, 1935, p. 108)

And as Gill (2009) notes:

Hare compares his task to that of a descriptive grammarian (see Hare 1964, i and 4) and he says explicitly that he is giving an account of moral terms as they are used, not as they might be used (see Hare 1964, p. 92). (as quoted in Gill, 2009, p. 216, footnote 1)

In short, noncognitivists took themselves to be accounting for what nonphilosophers are doing when they engage in moral discourse, and they rejected the notion that people were committed realists. Noncognitivism was an extremely popular position in the early half of the 20th century. It’s absurd to suppose that all competent philosophers presume folk realism. So the claim that all competent philosophers would agree that ordinary moral language is used in a realist way is simply not true.

I am finally referenced at this point:

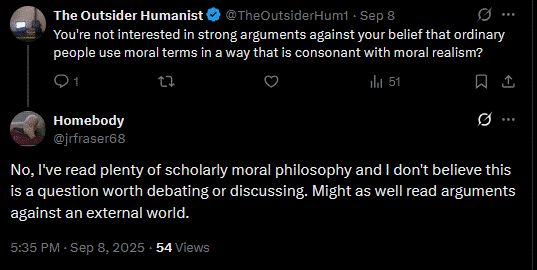

Cool. Unfortunately, Homebody thinks the claim that ordinary moral language isn’t realist is a non-starter. What’s this based on? The conversation continues with Homebody just insisting they’re not interested in this line of argument, culminating in this exchange:

5.0 Belief, phenomenology, and moral language

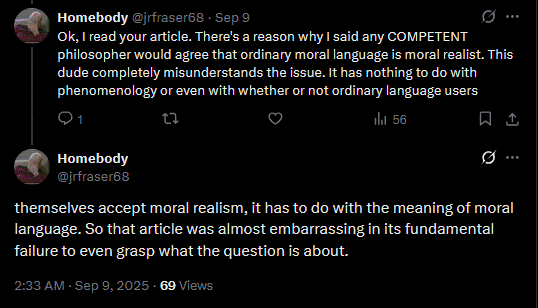

After more pressure, Homebody allegedly went ahead and read the blog post that’d been linked. Unfortunately, Homebody goes off the rails here, saying some strange things:

Let’s take a look at this claim:

Ok, I read your article. There’s a reason why I said any COMPETENT philosopher would agree that ordinary moral language is moral realist. This dude completely misunderstands the issue. It has nothing to do with phenomenology or even with whether or not ordinary language users themselves accept moral realism, it has to do with the meaning of moral language. So that article was almost embarrassing in its fundamental failure to even grasp what the question is about.

This is wrong on multiple levels. I allegedly completely misunderstand “the” issue. Why? According to Homebody, it’s because “the” issue isn’t about phenomenology. What is Homebody talking about? There isn’t one issue. There are multiple issues. The blog post begins by addressing one of those issues. And that issue is phenomenology. Note that the article begins with me quoting and then responding to a professional moral philosopher who makes the following claim:

Clearly there are objective moral values; it’s a basic datum of experience.

I then argue against this claim. How on earth would it make any sense to insist that “the” issue is some other issue aside from this one? Whether we have realist phenomenology just is the initial topic of this article, and it’s not like I just randomly decided that this is what philosophers are all focused on and is “the” issue central to contemporary metaethics. It’s an issue I opted to address because it is a claim made by a philosopher that I think is mistaken, a claim also made by other philosophers. Is JPA the only philosopher who has made claims about people having realist phenomenology? No, of course not. One of the claims used to try to establish a presumption in favor of realism is that various aspects of people’s phenomenology, or experiences, dispose them towards moral realism. Numerous philosophers, many central to contemporary analytic metaethics, appeal to allegedly widespread realist phenomenology. For instance:

Huemer (2007) and others defend moral realism by appeals to ethical intuitions, which he and others characterize as “seemings” or intellectual “appearances.” Indeed, the position is literally named phenomenal conservatism. Huemer is one of the most prominent and prolific defenders of non-naturalist moral realism. It doesn’t get more explicit than this.

Here’s another case of someone explicitly appealing to phenomenology to defend moral realism: “Feeling values: a phenomenological case for moral realism” (Hammond, 2019).

In David Enoch’s (2018) paper, “Why I am an Objectivist about Ethics (And Why You Are, Too)”, Enoch, a prominent contemporary moral realist, appeals to a phenomenological test as a method of revealing to his readers that they are (probably) moral realists.

On page 111 of The Moral Universe, Bengson, Cuneo, and Shafer-Landau (2024) explicitly state that appeals to phenomenology provide one avenue of potential support for their Reality thesis, the thesis that “there are moral truths and facts.” Earlier, on page 45, they construe their Unifying Principle of realism, that “The basic realist theses help to make sense of morality—in particular, the metaethical data,” and later on that same page state that the Unifying Principle that their various theses are not “a mere conjunction of claims about moral experience,” implying that their central theses do construe the “data” they describe in terms of moral experience, which is hard to square with the notion that a presumption in realism isn’t partially predicated on the claim that certain features of our experience/phenomenology support realism. Note that Bengson, Cuneo, and Shafer-Landau are three of the most central figures in contemporary analytic metaethics. This is not a fringe work but the culmination of decades of development on non-naturalist accounts of moral realism.

There is an entire literature on moral perception, i.e., there is an entire contemporary discussion dedicated to moral phenomenology, with much of it dedicated specifically to arguing for the ability to perceive moral facts. Claims like this are often leveraged in service of moral realism. See e.g., “Moral perception and the contents of experience” (Werner, 2016). See this book from Audi (2013) as well. Here’s an excerpt of a summary:

We can see a theft, hear a lie, and feel a stabbing. These are morally important perceptions. But are they also moral perceptions—distinctively moral responses? In this book, Robert Audi develops an original account of moral perceptions, shows how they figure in human experience, and argues that they provide moral knowledge.

Philosopher and Christian apologist William Lane Craig routinely appeals to “moral experience” to justify his position on moral realism, such as here. Here’s a partial transcription:

I would defend it by moral experience, that in moral experience we apprehend a realm of right and wrong, good and evil, and that we have no grounds or reasons to deny or think that moral experience is delusory.

Sharon Rawlette defends moral realism on the grounds that we have access to moral value as a direct aspect of our experience of the world (i.e., our phenomenology) in The Feeling of Value: Moral Realism Grounded in Phenomenal Consciousness. Here’s an excerpt:

In this book, Sharon Hewitt Rawlette turns our metaethical gaze inward and dares us to consider that value, rather than being something “out there,” is a quality woven into the very fabric of our conscious experience, in a highly objective way.

In “Values and Secondary Qualities”, McDowell (2013) characterizes Mackie as arguing that (at least part of) what contributes to Mackie’s error theory is a claim about our phenomenology having a realist character.

…These are just a handful of disparate examples that represent a broad and consistent consideration of the role phenomenology plays in establishing a presumption in favor of realism. And this is just what I could find after a brief search. Is it the only or primary source of evidence? No, of course not, but I don’t even imply this in the article. I begin by saying:

The belief that ordinary people think or speak like moral realists or experience morality in a way indicative of moral realism (i.e., moral considerations seem to concern matters of stance independent fact) is one of the most persistent articles of faith among contemporary analytic philosophers working in metaethics.

Note the distinction between think and speak and then distinguish both from how people experience morality. These distinctions are there for a reason. This brings us to the second claim, which is that “the issue”…

[…] has nothing to do with phenomenology or even with whether or not ordinary language users themselves accept moral realism, it has to do with the meaning of moral language. So that article was almost embarrassing in its fundamental failure to even grasp what the question is about.

There are at least three separate issues here:

Phenomenology: The experience, or phenomenology, of morality

Belief: Whether nonphilosophers “accept moral realism”

Discourse: How nonphilosophers use moral language

Homebody must not have read my article very carefully or tracked how he himself phrased things prior to this remark. Look at this earlier remark from Homebody, which was his initial remark addressing ordinary language:

I mean, you can argue all you want that you’re a moral skeptic, but you can’t argue that ordinary language users don’t use moral terms in a way that corresponds to moral realism. Any competent moral philosopher will grant that.

This specific phrasing is critical: “you can’t argue that ordinary language users don’t use moral terms in a way that corresponds to moral realism.” Note the emphasis on how they use moral language. Now, let’s look at what I say in my article. Here is my first sentence:

The belief that ordinary people think or speak like moral realists or experience morality in a way indicative of moral realism (i.e., moral considerations seem to concern matters of stance independent fact) is one of the most persistent articles of faith among contemporary analytic philosophers working in metaethics.

This is likewise a remark about how people use moral language. After this remark, I first address the experience of morality, since I begin with a quote about moral experience. Later on, I say this:

What do the Tsimane and Machigenga think about moral realism? When they make moral claims, do those claims appear to commit them to realism? Do they make moral claims? If so, what are some prototypical moral claims in the languages they speak? There are over 6000 languages in the world. How many of those languages is Andrew immersed in, to know what the structure of their moral claims (if they have them) look like, and how they function, not only in the abstract, but within the contexts of the cultures and populations that speak those languages?

Note how I consistently distinguish what people think about moral realism from how they speak about it. And note how I refer to the structure of their moral claims and how those claims function. I again make this clear with the next remark:

It’s not merely the case that psychological differences between WEIRD and non-WEIRD populations are attributable to enculturation alone, but language can facilitate or reinforce these differences.

This remark would make no sense if I were not distinguishing how we use moral language from psychological differences in how we think (in this case, about metaethics). I also want to stress that Homebody themselves characterized their distinction accepting realism and “the meaning of moral language” earlier in terms of ordinary speakers use moral terms. Note, then, that Homebody’s own characterization of the analysis of the meaning of moral terms is framed in terms of how ordinary speakers use those terms. This matches my own characterization.

I then go on to discuss language variation rather than psychological variation, quoting Majid and Levinson (2010):

The linguistic and cognitive sciences have severely underestimated the degree of linguistic diversity in the world. Part of the reason for this is that we have projected assumptions based on English and familiar languages onto the rest. We focus on some distortions this has introduced, especially in the study of semantics.

Observe the focus on linguistic diversity, languages, and the study of semantics. None of this is about whether “ordinary language users themselves accept moral realism”, though I do address that (separately, because I draw a distinction between them; and again, there are numerous studies assessing whether people “accept realism” and “accepting” realism doesn’t explicitly require conscious assessment, anyway). But it gets worse. I then say:

The analysis of moral claims in the English language in particular is central to much, if not most of the descriptive project of contemporary analytic metaethics.

Note that this is not a remark I drew from outside the article Homebody allegedly read to demonstrate that I’m aware of the distinction between whether ordinary language users accept moral realism and the meaning of moral language, it is a remark from the article itself. And observe how the focus is on the analysis of moral claims, not whether ordinary speakers accept moral realism or moral phenomenology.

In short: Homebody appears to have accused me of incompetence for failing to distinguish between the question of whether people “accept realism” and what Homebody claims to be “the issue,” which is instead the “meaning of moral language.” Homebody bases this accusation off of an article in which I explicitly draw the distinction and explicitly refer to the analysis of moral language as “central” to “much, if not most” of the descriptive project of contemporary analytic metaethics.

Given this, there’s a good chance Homebody did not read the article (or didn’t read all of it, or read it very carefully). But I don’t like to accuse people of being liars, and Homebody claims to have read it. I will leave it as an exercise to the reader to draw their own conclusion as to why Homebody would accuse me of incompetence for allegedly writing an article that construes “the issue” to be whether people accept realism and how they experience it, when “the issue” is in fact the analysis of moral language, when I simply don’t do this at all and in fact repeatedly and directly distinguish the latter and its centrality.

This is only natural, since I go into considerable detail about this distinction in my dissertation. In my dissertation, I make a point at the outset of noting that researchers conducting studies on how nonphilosophers think about metaethics consistently fail to distinguish between metaethical stances, i.e., people’s position on our beliefs about metaethics, and their commitments, which may be implicit and do not have to be reflected in any explicit belief or position that the person holds. I say this in part because I am well aware of the fact that much of analytic metaethics is construed in terms of the analysis of moral semantics, rather than the beliefs or attitudes of nonphilosophers. So let’s address this directly.

Regarding whether people “accept” moral realism, this is a nonspecific term and doesn’t explicitly mean something like “conscious endorsement.” Even if it did, (a) some of the experimental metaethics literature appears to be assessing this question and (b) this question is relevant to how people use moral language insofar as it provides indirect evidence about people’s linguistic practices. Why? Because all else being equal, one might expect one’s metalinguistic practices or beliefs about their practices to be more likely to coincide with those practices than to not do so. For example, if when asked about what they mean by the term “dog,” people insist that they’re not referring to turnips, this would be some evidence against any theory according to which the English word “dog” referred to turnips. We might scratch our heads in puzzlement if we then observed these people point at some turnips and say “look at those dogs over there,” of course, but the general point is that all else being equal what people accept about how they think is expected to be more likely to be consistent with how they speak than to be at odds with it.

Examples aside, my point is that if people explicitly accept moral realism when prompted (in the sense of judging it to be an appropriate reflection of what they or others mean when they make first-order moral claims), this would provide at least some evidence that they speak like moral realists or that realism is an implicit feature of their language. Is this strong evidence? No, my own position is that it is quite weak for reasons similar to those expressed by Genoveva Martí (2009; though see Machery, Olivola, & De Blanc, 2009). More generally, we may wonder: does this mean I think people’s claims about what they accept couldn’t be inconsistent with how they speak? Certainly not. I’m one of the least likely people to think this, given how critical I am of people’s capacities for introspection and my familiarity with people’s penchant for confabulation. But researchers studying whether people accept moral realism are not morons for doing so, and such evidence isn’t entirely irrelevant to how people speak. There are, for instance, studies that directly assess whether people think morality is “objective” (see e.g., Fisher et al., 2017). It is precisely because I’m aware of this literature that I framed my remarks in terms of what people think and how people speak and distinguish between the two. It is Homebody who is apparently unaware of this research. Ironically, I’m being accused of being oblivious to what the framing and focus of disputes in metaethics despite having read extensively about the relevant distinctions and explicitly drawing them and writing about them in my own work (see e.g., Bush, 2023, p. 24; p. 206; p. 238; Bush, 2023, Supplement 1, S8-17; Bush, 2023, Supplement 3, p. S519).

Given that this distinction figured prominently in my dissertation, and given that I’ve made a point of criticizing others for not being attentive to the distinction, Homebody’s presumption that I’m not aware of the distinction is ironic: Not only am I aware of this distinction, the distinction was so important to me that I went out of my way to include whole sections on the distinction in my dissertation, devise terminology specifically to facilitate drawing this distinction clearly, and included a glossary in part to assist readers in understanding the distinction. Collectively, this not only demonstrates my awareness of the distinction, but an unusually heightened preoccupation with it.

Now, one thing you may note is that I weave between how people speak and how people think. This is because my own view of language is one according to which meaning is determined by communicative intent. I don’t think it makes sense to talk about how people use moral language without regarding this as (at least in part) a question about their psychology. I reject conceptions of language that externalize meaning to something other than the psychology of speakers and the functional role terms and phrases play in social contexts. Nevertheless, I am conscious of the fact that this is one view about language and that other conceptions of language differ. And so I operate on the assumption that empirical data is relevant, both to understanding whether people accept moral realism and, more critically, how they use moral language. In other words, I take claims about the meaning of ordinary moral language to only be determinable by engaging with empirical data on how people use the language. I do not consider the meaning of ordinary moral claims to be an a priori matter. This does not mean that I’m not aware that the meaning of moral language has been and remains central to metaethical disputes, while whether nonphilosophers “accept” moral realism isn’t; it means that I take both claims to be empirical and regard data about how people think to be relevant to what they mean. I’m not alone in thinking this way. See, e.g., Gill (2009) or more importantly Loeb (2008). Note what Loeb has to say on the matter:

The claim that moral language is relevant to metaethical inquiry is not new. What is not often appreciated, however, is that the matter to be investigated consists largely of empirical questions. In saying this I do not mean to claim that empirical science can easily discover the answers, or even to presuppose that the answers can be uncovered at all. That remains to be seen. However, an inquiry into what, if anything, we are talking about when we employ the moral vocabulary must at least begin with an inquiry into the intuitions, patterns of thinking and speaking, semantic commitments, and other internal states (conscious or not) of those who employ it. (pp. 355-356, emphasis original)

Loeb specializes in metaethics. This is not an obscure remark from an unknown person, but someone well versed in contemporary analytic metaethics. And Loeb isn’t alone in thinking this way; experimental ethics has expanded over the past few decades and now includes input from many philosophers, including Knobe, Nichols, Pölzler, and many more. As such, my approach in the article Homebody ridicules is well within the scope of how contemporary analytic metaethicists frame and approach both metaethics as a whole and the analysis of moral language. Indeed, I didn’t develop my view from scratch; my approach was explicitly inspired by the work of analytic philosophers like Gill and Loeb. My entire framing of the issue is, in other words, derivative of the way the matter has been framed in the academic literature itself. Homebody’s suggestion that there’s something “embarrassing” about my framing is ironically, only an embarrassment for Homebody, since it suggests that Homebody is ignorant of the literature despite claiming to have read “plenty of scholarly moral philosophy.”

Homebody claims that my article was “almost embarrassing in its fundamental failure to even grasp what the question is about.” There was nothing embarrassing, almost or otherwise, about my article, but I can’t say the same about Homebody’s reaction to it.

References

Audi (2013). Moral perception. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bengson, J., Cuneo, T., & Shafer-Landau, R. (2024). The moral universe. Oxford University Press.

Bush, L. S. (2023). Schrödinger’s categories: The indeterminacy of folk metaethics (Order No. 30318258). Available from Dissertations & Theses @ Cornell University and the Weill Medical College; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2827166985). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/schrödingers-categories-indeterminacy-folk/docview/2827166985/se-2

Gill, M. B. (2009). Indeterminacy and variability in meta-ethics. Philosophical studies, 145(2), 215-234.

Hammond, T. (2019). Feeling values: A phenomenological case for moral realism. [Doctoral dissertation, Boston University]. OpenBU. https://open.bu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/fa70b292-3069-4e74-b6de-cb669d098add/content

Enoch, D. (2018). Why I am an objectivist about ethics (and why you are, too). In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), The ethical life: Fundamental readings in ethics and moral problems (4th ed., pp. 208–221). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fisher, M., Knobe, J., Strickland, B., & Keil, F. C. (2017). The influence of social interaction on intuitions of objectivity and subjectivity. Cognitive science, 41(4), 1119-1134.

Huemer, M. (2007). Compassionate phenomenal conservatism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 74(1), 30-55.

Loeb, D. (2008). Moral incoherentism: How to pull a metaphysical rabbit out of a semantic hat. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Moral psychology: The cognitive science of morality (Vol. 2, pp. 355-386). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Machery, E., Olivola, C. Y., & De Blanc, M. (2009). Linguistic and metalinguistic intuitions in the philosophy of language. Analysis, 69(4), 689-694.

Majid, A., & Levinson, S. C. (2010). WEIRD languages have misled us, too. [Commentary on Evans & Levinson, 2009]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 103-104. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1000018X

Martí, G. (2009). Against semantic multi-culturalism. Analysis, 69(1), 42-48.

McDowell, J. (2013). Values and secondary qualities. In T. Honderich (Ed.), Morality and objectivity (Routledge Revivals) (pp. 110-129). New York, NY: Routledge.

Rawlette, S. (2016). The Feeling of Value. California: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Werner, P. J. (2016). Moral perception and the contents of experience. Journal of Moral Philosophy, 13(3), 294-317.

Great post. I myself have used preferences about ice cream flavors as an intuitive, accessible way to illustrate the nature of subjective preferences, but it was not my intent to also imply that on subjectivism moral preferences are trivial or mundane. I will keep your post in mind the next time I write about the nature of subjective preferences.