"Morality is subjective" ≠ Morality doesn't exist

Twitter Tuesday #38

1.0 Introduction

There’s nothing new here. But in my tireless efforts (okay, fine, I’m a bit tired at this point) to document the ubiquity of misunderstandings and bad objections to moral antirealism, I will (for now) continue to highlight cases like these.

This tweet is a great example of the idea I criticized in Jack and the Giant Qualia:

Simply put, Wendell sets up a false dichotomy: one must either accept that morality is objective or accept that it doesn’t exist at all. This is a form of narrative control. One insists that only one’s own conception of the way something is can be correct, and that therefore anyone who denies one’s conception of the thing in question denies the thing exists at all. As a reductio, I described a scenario in which one person approaches another holding a handful of beans and declares them to be magical beans. When the other person agrees that they see the beans, but denies that they are magical, the one holding the allegedly magic beans insists that because they are magical beans, if the other person denies they are magical, then they deny the person is holding beans at all. But since the person is clearly holding beans, it would be absurd to deny their claim that they are holding magical beans.

This story illustrates how a person can insist that their conception of the nature of a thing is the only conception on the table, so if anyone denies their conception of the nature of a thing, that person must deny the thing exists at all. This way of thinking about the nature of things entangles one’s conceptions of the thing with the thing itself. The result is that one functionally treats others as though they’re not allowed to disagree about the nature of the thing in question: they must grant your conception, or abandon claims about the thing in question altogether, beyond denying its existence.

But other people are under no such obligation. They can simply reject your conception. Wendell has, likely unintentionally, engaged in precisely this kind of objectionable narrative control. We should resist this when it occurs. There is more to this post, though.

1.1 Speaking for others

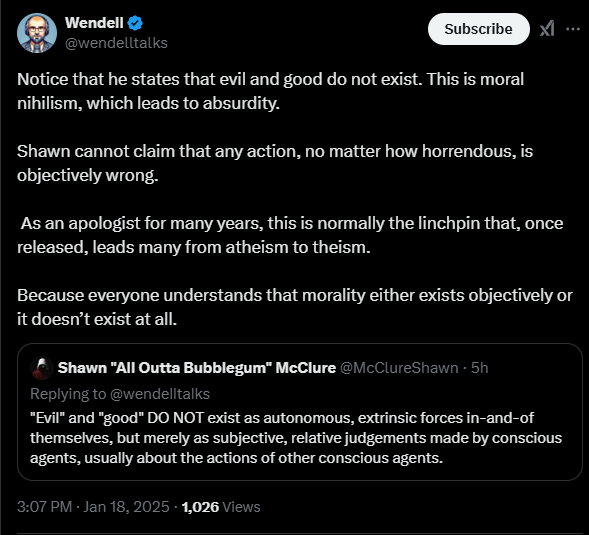

What’s especially objectionable about this particular instance of magical beans is that Wendell explicitly insists that the person he’s responding to “states” matters in a way that comports with his framing, even though they explicitly say something inconsistent with this framing. Here is Wendell’s first remark:

Notice that he states that evil and good do not exist. This is moral nihilism, which leads to absurdity.

Wendell is responding to a tweet by Shawn, which, as you can see, does not state that good and evil do not exist, and does not express a moral nihilist stance. Shawn says:

"Evil" and "good" DO NOT exist as autonomous, extrinsic forces in-and-of themselves, but merely as subjective, relative judgements made by conscious agents, usually about the actions of other conscious agents.

To say that evil and good don’t exist in one way, but instead exist “merely” in some other way entails a position according to which evil and good do exist, but are conceptualized in non-objective terms. Yet Wendell opts not simply to characterize this as the view that good and evil don’t exist at all, but to say that Shawn states this. Shawn does not state this.

It is not okay to presume that because you think you are correct about some view, that it is okay to frame what other people think or say in terms of your views about what is correct, even when that person appears to be making claims explicitly contrary to the view in question.

To illustrate why I find this objectionable (and why you should, too), let’s consider a magic beans scenario involving a real object. Suppose you encountered someone who pointed at the Statue of Liberty and said:

The Statue of Liberty is the literal incarnation of the Goddess of Freedom.

Suppose you doubt this claim. Would this entail that you don’t believe the Statue of Liberty exists?

No. It would not mean this. It is logically consistent to hold the following two beliefs:

The Statue of Liberty exists.

The Statue of Liberty is not the literal incarnation of the Goddess of Freedom.

Whether a person’s views are logically consistent or not depends on that person’s views. And whether a person believes something in particular depends, trivially, on what that person believes. Yet Wendell seems to believe that because something like the following claim is true:

Either morality exists objectively or it doesn’t exist at all

And that

Everyone “understands” this (i.e., correctly believes it’s true)

…that therefore if anyone claims that morality is not-objective, that they therefore claim that morality does not exist at all.

Wendell has simply helped himself to the claim that everyone “understands” that his position is correct. Wendell appears to be making an incredibly bold empirical claim: a claim that everyone holds a particular view about metaethics. Does he present any arguments or evidence for this? No. And I very much doubt he would have anything approaching a decent argument or any substantive evidence for such a claim.

I don’t think this statement is true. Wendell doesn’t speak for me, and probably doesn’t speak for almost anyone else on the planet. What’s weird about Wendell’s claims is that in virtue of his belief that everyone “understands” something he believes to be true, that he’s in a position to characterize what others say as “stating” things that presuppose their agreement with his claims, even when that person appears to be saying something inconsistent with this.

Nobody should speak for others in a philosophical exchange. So my advice for Wendell is to speak for yourself, and do your best to accept that other people can and do hold views contrary to your own.

1.2 You can’t say that!

Wendell’s next remark is another common pseudo-objection critics throw at antirealist views:

Shawn cannot claim that any action, no matter how horrendous, is objectively wrong.

Yes, anyone who doesn’t believe that anything is objectively right or wrong cannot consistently and sincerely say that anything is objectively wrong. So what? Of course they can’t say that. What does saying that get you? Is Plato going to pop out of a cave and high five you? Do golden motes of light manifest around you whenever you say something is objectively wrong, blessing you with their holy grace?

Imagine objecting to atheism by saying:

Atheists cannot claim that any gods exist.

…as if that were some kind of objection. Of course, it wouldn’t be.

Note the inclusion of “no matter how horrendous” as if somehow if something were more horrendous this should prompt one to be more willing to call it objectively wrong. Something being “objectively wrong” is a qualitative difference. It has nothing to do with it being “really” wrong, nor is something “more” wrong if it’s objectively wrong. Yet critics of antirealists will imply that if we don’t accept that the worst possible things are objectively wrong, that this is somehow bad, or objectionable, or awful. Why? What exactly is the reasoning here? If the only issue is that we can’t invoke the magic word “objective” when referring to some terrible action, this is not much of a price to pay. Words aren’t magic. That we can’t say something isn’t important at all.

1.3 Bald assertions

Finally, Wendell says:

Because everyone understands that morality either exists objectively or it doesn’t exist at all.

No they don’t. There is no good reason to think everyone understands this, nor is there any good reason to think this is true.

2.0 Moral senses

Now let’s turn to responses to Shawn’s remark:

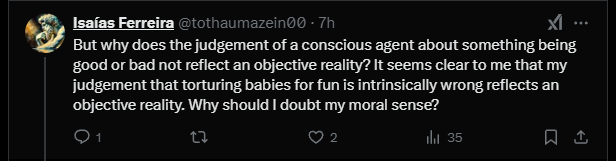

Here’s the first:

This appeal to private, inaccessible claims that one “senses” moral truth is a pernicious force in discussions about metaethics. It grants each individual epistemic carte blanche to assign any arbitrarily greater amount of weight to their intuitions or seemings than whatever evidence anyone else can muster against their “sense,” while effectively putting all the work on everyone else to persuade them, while they can sit back and don’t have to do any further philosophical work because of their alleged “sense.”

Anyone who makes such appeals effectively sets up an epistemic game with a score card of:

Themselves: An unknown and possibly variable amount of evidence for their views between 1 and ∞ points.

Opposition: 0 points.

Now it’s the opposition’s job to provide “defeaters” sufficient to score more points against the person with a “sense” of what’s true than however many points you’ve plopped into their belief.

And how many points do they have? Who knows! Appeals to private senses, seemings, and intuitions are completely inaccessible to others. So even if they did serve as a legitimate form of evidence, that evidence is not directly available to anyone else. Its strength, and even its existence, cannot be independently corroborated or verified. I call this an epistemic blank check.

3.0 Presumptions, dishonesty, and normative entanglement

Here we see another cluster of common missteps in discussions about metaethics:

Nothing about denying “moral absolutes” in the sense of stance-independent moral truths involves denying that it is morally wrong to torture a baby. This might otherwise seem like a request for clarification, but this is immediately followed by the notion that by Shawn’s logic “it’s not morally wrong as there is no moral absolute.”

This is very strange. Shawn never agreed that nothing is morally right or wrong unless it’s “absolutely” right or wrong (which I am hoping means stance-independently, since otherwise that would be yet another mistake). Yet what’s especially frustrating about this remark is the last part:

I think if you are truly honest with yourself - it is known deep within your heart / being that is [sic] is fundamentally absolutely wrong!

This kind of remark is extremely frustrating. Such remarks suggest that people who express antirealist views are in some way dishonest, because they “know” that things are wrong in a realist sense. There is no good evidence or reason to believe this is true in this case or in any others that I know. People don’t have mindreading powers; such remarks often rest on the confidence of the accuser that people simply must agree with them.

Some of us simply do not. I don’t “know” deep down that anything is “fundamentally absolutely wrong.” This is just like those cases where Christians tell atheists that they know God is real “deep down in their hearts.” It’s patronizing. But more importantly, it’s very likely false.

I'm not a moral realist. I am a moral nihilist, although I think the term "amoral" is better.

Of course, I agree that Wendell's argument is bogus. He assumes that moral nihilism is somehow absurd, simply because it is moral nihilism. That is like saying "The atheist's position is absurd, because the atheist cannot make any claims about God."

However, his argument is not based on a false dichotomy. If you reject the existence of an objective/cosmic value standard, you have rejected morality. You could still have moral intuitions, but you would have to recognize that they are not the awareness of a cosmic value standard, and thus not "moral".

Let me rework your magic bean analogy. Someone says "These are magic beans (cosmic values)", and I say "No, they are just beans (moral intuitions, acquired by living in society)". Yes, the beans (some kind of values) exist, but they are not what the person believes they are. They are the internalization of social/cultural values.

The point of moral claims is precisely that they supposedly are about a cosmic value standard. That's what makes them "moral". If someone says "X is evil", he means that X violates a cosmic standard, not that X violates a social, cultural or personal standard. He believes that the standard applies to everyone. Morality is used as a pseudo-foundation, much like the notion of God. To have that memetic function, it must be an external, cosmic source of authority.

I enjoyed your discussion about Sam Harris, btw.

"Whether a person’s views are logically consistent or not depends on that person’s views. And whether a person believes something in particular depends, trivially, on what that person believes. "

This is untrue, the logical consistency of a set of beliefs can be analyzed objectively, using methods independent of mind, to confirm whether there is a contraction.

A person who believed that 1=1 and 1=2 would have logically inconsistent views, regardless of what they believe.