Nothing Can “Give” You a Reason

Reification, pragmatics, and desire-reductivism

When my brother was younger, he had a strong preference for sandwiches to be cut into triangles instead of squares. Yet as he aged, he grew out of this. My verdict: he came to see that there wasn’t really any reason to care about the shape of the sandwich. He came to see that he was aiming at some things that he didn’t really have any reason to aim at. – Bentham’s Bulldog

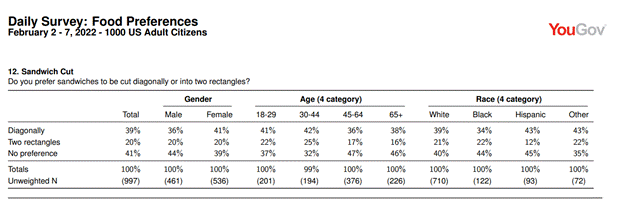

I turn 40 this year. I still prefer my sandwiches to be cut into triangles. Some data suggests that, at least in certain societies, most people do. This mysterious, unshakable conviction invites us to consider the most fundamental question in all of philosophy:

Why?

Is this preference an arbitrary, irrational whim? Or does it point to something deeper about the human psyche that, once revealed, would shed light on the most intractable questions in philosophy and yield profound insight into the human condition?

The answer is…probably neither. Yet the belief that one’s preferences, however innocuous, arbitrary, or weird, could be irrational, unreasonable, or mistaken figures into a broader set of beliefs and commitments largely distinctive to academic philosophers: the notion that there are stance-independent reasons to act in certain ways. According to Bentham and others, desires may not give us reasons to do anything. Instead, reasons are given to us by facts or considerations that have nothing to do with our desires, goals, or preferences. When deciding what to do, your primary concern shouldn’t be to ask, “What do I value?” or “What do I want?” but to instead ask “What external reasons do I have to do one thing rather than another?”

I believe this view is profoundly mistaken. While psychologists have yet to hammer out a precise set of distinctions that cleanly partition, collapse, or eliminate folk notions like desire, preference, goal, aim, impulse, and so on, we may still roughly appreciate that voluntary action requires motivation, i.e. those factors that prompt and maintain goal-directed behavior. It is not clear to me how anyone could ever voluntarily do anything that they didn’t want to do, more or less on tautological grounds: to act voluntarily just is to act on one’s goals or desires (again, with the acknowledgement that the language of “goal,” “desire,” and so on is imprecise here, and may need to be refined).

Thus, even if there were “reasons for action” independent of our goals, desires, preferences (or whatever other term we want to use), my general outlook is that we’d still need to desire to comply with such “reasons” for them to have any impact on our behavior. Maybe I’m mistaken or confused about this, but I’ve never seen a plausible alternative conception of voluntary action. If you know of one, feel free to leave a comment or respond to this post. But, speaking for myself, as far as I can tell I am only interested in acting on my desires, and even if there were reasons for me to do things distinct from those desires, I have no desire to factor such reasons into my deliberations. But this post isn’t about my conception of deliberation, desire, or motivation. It is about the case Bentham makes to the contrary. My goal in this post will be to systematically evaluate the case Bentham makes against the notion that desires “give us reasons” and in favor of the view that our reasons are “given” to us by facts external to our desires.

My main thesis is simple: Bentham provides no good arguments for such a view. While examining the shortcomings of his arguments, I also argue that his entire perspective is predicated on a more fundamentally misguided notion that “reasons” are a distinct property or phenomenon that could in principle be “given” by anything. I provide an alternative conception of our use of the term “reason” that strips it of any distinct metaphysical import or conceptual independence by deflating its use in English and illustrating how talk of “reasons” can be understood in ways that don’t require or presuppose that one can literally “have” reasons. In so doing, I reject both mainstream analytic conceptions of “reasons” to maintain that they are given to us by our desires, and realist conceptions of “reasons” that maintain that they are given to us by something other than our desires. Simply put, nothing gives us reasons.

1.0 Current and Previous Critiques

In a recent post, “Reasons and Moral Anti-Realism,” Bentham’s Bulldog raises an objection to moral antirealism: namely, that moral antirealism can’t account for genuine “reasons.” This is taken to be some sort of severe shortcoming with moral antirealism. It isn’t, and Bentham continues a pattern of offering tepid objections to antirealism. For previous critiques of Bentham’s takes on metaethics, see here:

Bentham’s overarching objection appears to be that he finds it intuitive that we have stance-independent normative reasons, i.e., reasons for action that are not reducible to one’s desires. Moral antirealists deny this, and while antirealists often offer various alternative accounts of normative reasons, he doesn’t consider these to be satisfactory.

2.0 Ambiguity about reasons

The problem with this objection to antirealism is that it is completely trivial. Here’s why. Moral realism is typically characterized as the view that there are stance-independent moral facts. These are facts about what is morally right or wrong that are true independent of our goals or desires. Moral antirealism is the view that there are no stance-independent moral facts. For an antirealist, if there are reasons, those reasons cannot be independent of our desires.

Thus, insofar as moral facts are “reason giving,” only moral realism, by definition, can “give” us reasons to act in a way independent of our desires. For comparison, only theists can believe that God created the universe. It is a surface-level entailment of atheism that it is inconsistent with the belief that God created the universe. By “surface-level,” I mean that the entailment in question is a direct and straightforward implication of the position in question, rather than a non-obvious one that someone familiar with the position could reasonably overlook.

Likewise, it is simply part of the surface-level features of realism and antirealism that realism can provide us with stance-independent reasons and antirealism can’t. As a result, to object to moral antirealism on the grounds that it fails to furnish us with stance-independent reasons is a trivial objection. It is not meaningfully different from objecting to atheism by asserting that:

It seems that God created the universe. But atheists deny that God created the universe, so atheism is unable to account for this datum.

Compare this to how Bentham begins his post:

Here is something that seems obvious to me: sometimes, I have a reason to perform an act. I have a reason not to stab myself in the eye for no reason. I have a reason to eat when I am hungry. I have a reason to eat healthy foods. Can anti-realism accommodate this datum?

If by “reason,” Bentham just means the kinds of reasons that are only consistent with a realist account, then the objection to antirealism based on these remarks is just as trivial as the objection to atheism I just presented. In other words, suppose that the kinds of reasons Bentham takes to be the datum just are stance-independent reasons. If moral antirealism rules out that there are such reasons, then it’s simply a logical entailment of antirealism that we don’t have such reasons, just like it’s a logical entailment of atheism that God didn’t create the universe. And objecting to atheism on the grounds that because the “datum” just is that God created the universe presupposes that atheism is false. If, instead, “reason” doesn’t refer only to the kinds of reasons inconsistent with antirealism, then it is open to the antirealist to point to conceptions of realism consistent with antirealism, which satisfies the condition of accommodating the “datum” in question. Bentham’s entire argument thus relies on concealing the emptiness of his objection behind a veil of ambiguity: once disambiguated, Bentham’s objection is either trivial or false.

As an aside, Bentham’s use of “datum” is a poor way to frame a philosophical matter. His phrasing is ambiguous, and the term “datum” is inappropriate for use in philosophical contexts like these. Just what is the “datum” here? That certain things seem obvious to Bentham, that we in fact have the kinds of reasons Bentham supposes we do (whatever that means), or something else? And does the datum consist in any distinctive account of “reason” or not? If so, what is that account? If not, how can it serve as “datum” if the content of “reason” hasn’t been disambiguated in such a way that we know what it consists in? For comparison, one couldn’t treat an object in a box as datum a theory must account for if one isn’t clear about whether the object is, e.g., a fossil rabbit from the Pleistocene or the Precambrian. After all, the former would be utterly mundane while the latter would upturn the theory of evolution. Likewise, the notion of a “reason,” absent disambiguation, remains in an indeterminate state such that whether an antirealist could or couldn’t account for the “reasons” in question will turn on what’s meant by “reason.” If by “reason” Bentham means the sorts of reasons that are inconsistent with antirealism, then it can’t, while if Bentham means the sorts of reasons that are consistent with antirealism, then it can. Another problem is the ambiguity about whether the datum is Bentham’s intuitions, or something other than Bentham’s intuitions. Some philosophers claim that certain positions they regard as intuitive enjoy some kind of public or general default status. It’s not clear whether Bentham thinks this or not.

Another reason I dislike this language is because it coopts a scientific term. “Datum” is often used to convey information or facts one has acquired that has a distinctively empirical connotation. But setting that matter aside, it is most distinctively associated with the sort of information that is taken for granted at the outset of inquiry. Here is the first definition I found when searching for a standard dictionary definition of “datum”:

Something given or admitted; a fact or principle granted; that upon which an inference or an argument is based; -- used chiefly in the plural.

When someone like Bentham claims that something is “datum,” this implies or could readily be interpreted to imply that the claim in question should be treated as a given or “admitted.”

As such, it is very important to establish whether the “datum” in question is simply Bentham’s intuition on the matter, or whether the claim that there are “reasons” of the sort Bentham supposes there are is supposed to be the datum. If the former, the antirealist’s task is a lot easier. It’s not so daunting to account for why Bentham might have a particular intuition, nor is the fact that Bentham has such an intuition terribly threatening to whether antirealism is true. If, on the other hand, the datum is supposed to be that we have such reasons, then it becomes more critical than ever to know what kinds of reasons Bentham thinks the datum consists in. If they are the kinds of reasons inconsistent with antirealism, then Bentham’s objection is trivial. Imagine if, for instance, I claimed that part of the “datum” philosophers must “accommodate” is that:

Moral realism seems false.

One may then proceed as if it were established that one’s interlocutors have or at least ought to grant that “moral realism seems false.” Now, if the datum Bentham is presenting is merely that Bentham personally finds certain things to be obvious, that may tell us something interesting about Bentham’s psychology, but it’s not the sort of thing I think serious thinkers should spend a lot of time devising theories to accommodate. Why should I or anyone else invest time and effort in assuaging Bentham’s personal predilections? It “seems obvious” to many people that paranormal powers are real, that reptile aliens have infiltrated the upper echelons of society, that astrology provides valuable insights into human nature, and so on. People believe all kinds of nonsense. Why should anyone care what Bentham thinks?

If, on the other hand, the “datum” is something more public and less personal, then I don’t grant that there is such “datum”. That’s something Bentham would have to argue for. But in typical fashion, Bentham, like many analytic philosophers, isn’t very clear about what he means. At the time of writing, I was able to resolve some of the ambiguity. I asked Bentham for clarification on the latter point, and fortunately he obliged. I said:

Bentham’s Bulldog Can you clarify what the datum is here? Is it:

(1) You find it obvious we have reasons to perform certain acts.

(2) There are reasons of the kinds you list.

(3) Something else.

Bentham’s response was:

That there are sometimes reason [sic] to do things.

This confirms that the “datum” we are to accept is that “there are sometimes reasons to do things.” Unfortunately, this doesn’t address a second ambiguity. Following this response, I asked Bentham:

There is further ambiguity when you say that “There are sometimes reasons to do things.” What kinds of reasons do you think are part of the datum? Stance-independent reasons in particular, stance-dependent reasons in particular, or something else?

It’s been several days since I asked, but at the time of writing he has not responded. At this point I don’t expect a response. So we’ll proceed with this question unanswered. Note how I included a third option. The “reasons” Bentham takes to be the datum could be stance-independent reasons, stance-dependent reasons, or they could be something else. This could be a combination of the two (“reasons pluralism”), or he might believe there’s a determinate answer but he doesn’t know (“reasons agnosticism” I suppose), which would be consistent with pluralism, or he might go another route entirely, and suggest that the reasons in question are reasons tout court, i.e., simply “reasons” without further qualification. This possibility was suggested by @Tower of Babble, who said:

Can’t he just say reason tout court? Like why should he specify ‘stance-dependent’ or ‘stance-independent.’

He could say this, but I don’t think it would be a very convincing move. Let’s draw a distinction between abstract concepts and concrete concepts. Take the notion of fruit. Fruit is an abstract concept that can refer to any number of objects: apples, bananas, pears, and even, metaphorically, buildings or achievements, as when one speaks of the “fruits of one’s labor.” Can a person have a fruit? Yes, they can, as long as we’re clear on what that means. A person can have a fruit in the sense of having a concrete instance of a fruit: they can have an apple or a banana or a grapefruit. But a person cannot literally have a fruit simpliciter. That is, one cannot be in possession of an object, and that object is a fruit, but it isn’t any kind of fruit in particular.

This just isn’t how “datum” works. If people have reasons, they have something in particular. I responded to Tower of Babble on a similar note:

[…] Let’s say all fruits are apples or bananas. As part of our data, we know that everyone has one fruit. Can they literally have a fruit simpliciter? I don’t think they can. It’s not possible to literally have an abstract object. All data is concrete, even if you don’t know what the data is.

There’s also the matter of access to knowledge about the objects. Is the epistemology of having stance independent and stance dependent reasons the same? How does he know we have reasons is part of the datum? If the way by which he knows is distinctive to one or the other kind, shouldn’t that matter?

Personally, I suspect not being specific would be hand wavy, and might not make much sense. I don’t think you can literally have a reason simpliciter. Maybe you could know you have a reason but not be sure what kind, but I’m not sure how that’s supposed to happen.

I think he might want to say this anyway. Huemer said similar things when I spoke to him. But I think this might be a rationalistic error.

I also note here that there is an epistemic question on the table. How did Bentham determine that the fact that we “sometimes have reasons” is part of the “datum”? If it involved introspection on a priori considerations, then does this process somehow furnish one with knowledge that one has reasons, but doesn’t tell one what kind of reasons one has? If so, why? And why should we think that the epistemic access one would have to stance-independent reasons would be the same as the way one would access stance-dependent reasons? One might suppose that knowledge of the latter would exhibit a distinct phenomenological profile.

Before proceeding, I want to address two caveats.

3.1 Surface-level entailments & reasons-first approaches

One objection to my claim that Bentham’s central thesis is trivial is simply deny that it’s trivial. Sometimes the entailments or implications of a philosophical position are non-obvious. By drawing attention to these features, one can make meaningful progress in raising a substantive objection to a position. Suppose a philosophical position seems entirely plausible at first glance. However, it turns out that an implication of this position is that 2+2=43, or that the sun is made of bologna. Once one realizes that these are implications of a seemingly plausible position, one might then be inclined to reject the position. @Tower of Babble offered a response along these lines here:

Re your first two paragraphs: If I say something like “classic utilitarians are committed to the acceptability of utility monster cases, but that’s obviously crazy!” It seems like it would be silly to respond “that’s just an entailment of the view.” The point is that the view has unacceptable entailments, that many people might not find obvious, but when pointed out to them they come down hard against said view.

I agree that this would be entirely appropriate in the case of utility monsters as a non-obvious objection to utilitarianism. However, I don’t think this is analogous to the notion that antirealism can’t account for the kinds of reasons realists think there, because I take the inconsistency between antirealism and such reasons to be an obvious or surface-level entailment of antirealism. Why do I think this? Take utilitarianism: this is the view that one ought to impartially maximize utility. It is an entailment of the view that if there is an entity that enjoyed eating people so much that it would maximize utility to feed everyone to it, that one ought to do so. That’s not necessarily obvious to people until you point it out.

Now consider moral antirealism. Moral antirealism is typically construed as the position that there are no stance-independent moral facts. But a case could be made that moral antirealism could be equally or better characterized as the position that there are no stance-independent reasons. Why? I offered an explanation for why this would be a reasonable way to characterize the realism/antirealism dispute is here. I’ll reproduce the relevant portion here with some minor changes:

The dispute between realists and antirealists is typically construed in terms of whether there are stance-independent moral facts. But this is just one way of construing the dialectic. Another way places normative reasons at the center of the dispute.

Indeed, many contemporary metaethicists take just such a reasons-first approach according to which normative reasons are the most fundamental unit of theoretical consideration in metaethics, not facts about what one should or shouldn’t do, what’s good or bad, and so on. Instead, these concepts are construed as downstream of and dependent on reasons. This approach has grown in popularity in recent years. Schroeder’s “Reasons First” provides one example. Here’s a quote from the description:

“In the last five decades, ethical theory has been preoccupied by a turn to reasons. The vocabulary of reasons has become a common currency not only in ethics, but in epistemology, action theory, and many related areas. It is now common, for example, to see central theses such as evidentialism in epistemology and egalitarianism in political philosophy formulated in terms of reasons. And some have even claimed that the vocabulary of reasons is so useful precisely because reasons have analytical and explanatory priority over other normative concepts-that reasons in that sense come first.

Reasons First systematically explores both the benefits and burdens of the hypothesis that reasons do indeed come first in normative theory […]”

In other words, an entirely conceptually legitimate way of defining the realism/antirealism dispute just is as a dispute about whether we have the kinds of reasons Bentham is talking about in the article or not.

This isn’t simply a matter of it being some concealed, non-obvious entailment of antirealism. Contemporary metaethicists quite literally can and have described the landscape in such a way that the best way of construing moral realism and antirealism would be that:

Moral realism is the view that we have reasons to do things independent of our stances.

Moral antirealism is the view that we don’t have reasons to do things independent of our stances.

[…]

It’s also worth noting that the centrality of reasons in contemporary ethics is closely associated with Parfit, the very person featured in the image in Bentham’s post, and that Bentham’s own realist perspective appears to be heavily inspired by Parfit.

I regard definitions of moral realism/antirealism in terms of facts rather than reasons to be a contingent, incidental feature of the recent history of metaethics; it could just as readily have gone the other way around, and in the coming decades defining realism and antirealism in terms of reasons rather than facts could become the norm.

As such, when I say that what Bentham is arguing is trivial, I am doing so in light of my familiarity with the contemporary metaethical landscape and where I take Bentham’s views and inspiration to fall within that landscape.

Roughly, the issue is this. An entirely defensible approach to defining moral realism is as the view that there are stance-independent reasons. And if one has a stance-independent reason, that reason is by definition a reason that cannot depend on or be reducible to your desires (or anything else that constitutes a stance; “desire” would either be a kind of stance, though some might even just use “stance” and “desire” interchangeably, which would make my point even stronger).

That antirealism doesn’t allow for us to have reasons independent of our desires is, if not a definition, very close to one. This is why Bentham’s objections are trivial. They are about as close as one can get to complaining that something is false because the contrary is true without saying exactly that.

3.2 “Desires” and stances

This construal in terms of independence of desires is inaccurate for my taste. I do not think we can just neatly treat the stance-independence/stance-dependent divide as reducible to desire-independent/desire-dependent divide, since the ways in which moral facts can depend on stances is either not fully identical to stances being desires or the term “desire” would have to be artificially widened to encompass the sorts of positions that typically fall within the ambit of antirealism. If, for instance, one is a cultural relativist, then one may believe moral truth for a given culture is determined by a crude majority of members of that culture, or by whatever institutional forces hold power, even if it isn’t a strict majority. While the consensus or the position of the elites might bottom out in desires, it might not (more on this in a moment), but the critical point here is that even if moral facts depended in some way on desires, they wouldn’t necessarily be your desires.

So it is entirely consistent with moral antirealism that there are facts about what you have reason to do that are not reducible to your desires. Second, “desire,” may not capture the full range of psychological states that can serve as stances, and it is questionable whether a stance need be literally constituted by a desire in the first place, since a stance could be hypothetical or held in some non-psychological sense, such as adherence to a moral code outlined in a book. If what one had reason to do depended on the stances of different books, then one would have a kind of relativism, and one would have a kind of antirealism since those moral facts weren’t true independent of a stance; it’s just that the stances in question would be the stances of books. The content of those books need not reflect the desires of anyone, or at least anyone currently living. As such, at the very least, antirealism allows for there to be reasons to do something that don’t depend on any occurrent desires.

Lastly, I’ll just note that “desire” is a piece of technical philosophical jargon used in philosophical contexts, and that it may or may not correspond to any distinct cognitive phenomena recognized by contemporary cognitive psychology.

4.0 Misleading modifiers

Recall that Bentham asks whether antirealism can accommodate the “datum” that we sometimes have reasons. Bentham continues:

I believe that the answer is no. As Parfit suggested, if moral anti-realism is true, all our reasons to act are built on sand. No action is more worth taking than any other. There might be actions that we are, in fact, psychologically disposed to take. But there are none that we have genuine reason to take.

Bentham continues with the unfortunate use of misleading modifiers like “genuine.” Just what does “genuine” mean here? Antirealists and realists are going to have different accounts of reasons. Why should we simply refer to the realist’s reasons as “genuine”? What makes them genuine? Bentham’s use of “genuine” serves a similar role that terms like “really,” “actual,” and related terms. This label naturally invites us to regard the antirealist’s conception of reasons as somehow ingenuine or fake. Sure, the antirealist may offer us “reasons,” but they are somehow counterfeit, or not the real thing. This is normatively loaded language that subtly indicts alternative conceptions. It is rhetorically manipulative. And it’s disappointing to see Bentham continuing to employ this kind of rhetoric in his articles. I present an extended critique of using terms like “genuine” in this way here. Here’s an excerpt:

The idea here is that the realist will claim that their conception of morality or value involves a belief in “real,” or “true” or “actual” or “genuine” value, with the implication that the antirealist’s conception of morality or value is somehow not real. This is why I have dubbed this use of deceptive modifiers the fake cheese fallacy.

The fake cheese fallacy: The use of deceptive modifiers, when describing one’s own position in relation to other positions, e.g., “true,” “genuine,” or “real,” that give the misleading impression that one’s own position is in some way more likely to be correct or desirable. This works by exploiting the connotations with colloquial uses of these terms.

Example: “As a realist about moral value, only I think that actions are really right or wrong.”

In fact, the fake cheese fallacy is baked into the very names of the competing positions. Realists are, after all, realists. They think morality is “real,” allegedly, while antirealists don’t. This is, of course, also misleading and unhelpful.

I’m an antirealist, but I don’t think morality isn’t real; I think that there are no stance-independent moral facts. What would it even mean to say morality isn’t “real”? This leaves open what it is we’re saying isn’t real. While I and other antirealists don’t think there are stance-independent moral facts, this does not mean that we think nothing matters, or that we don’t oppose hurting people, or that happiness isn’t desirable and worth pursuing, and so on. Yet all of this is commonly implied or assumed by critics, and suggested by moral realists who ought to recognize none of this follows from our views (or, they might insist, it does follow; in which case they’d need an argument for this). We differ from moral realists not in that we don’t care about the same things, and that we can do so with just as much fervor as they do; it’s just that we don’t think this involves distinctive metaphysical and conceptual commitments.

While denying that anything is valuable in any respect at all is consistent with thinking that if things aren’t good or valuable in the realist’s sense, that they aren’t good or valuable at all, this isn’t an entailment of antirealism; an antirealist is free both to reject realist conceptions of goodness/value and to reject the notion that only realist conceptions of goodness/value are “true,” or “genuine” or “real.” The antirealist who doesn’t do this may be buying into realist’s notions that only their conceptions of morality and value are legitimate, even if the antirealist proceeds to deny that the realist’s position is true. And this may be due to a persistent campaign by realists to employ deceptive modifiers like “real” and “true,” modifiers that both create an unearned positive association with realist positions, and, if repeated often enough, can take advantage of truth-by-repetition; as the expression goes, if a lie is repeated often enough, it becomes the truth.

I don’t believe Bentham has adequately addressed the objection that his use of a term like “genuine” serves no legitimate philosophical purpose and instead serves an exclusively misleading rhetorical function. Unfortunately, many antirealists do buy into the realist’s tendentious framing, granting that the antirealist must accept that they don’t have real or genuine reasons. Some antirealists go even further, denying that we have reasons without any caveats or qualifications, or denying that there are “moral facts” at all, or that morality “is real.” There are defensible ways of characterizing antirealism in these terms, but framing things in this way without a mountain of qualifications unnecessarily cedes rhetorical ground to realists, who are often all too happy to exploit these rhetorical vulnerabilities to make antirealism look bad without actually delivering any philosophically substantive blows to it.

5.0 The analytic antirealist

Bentham moves on to address his concerns with antirealist conceptions of reasons:

The anti-realist presumption is generally that one’s reasons to behave in some way are given by their desires. This is supposed to be the default. Yet I do not see why the mere fact that one wishes to perform some act gives them a reason to do it. Why do my reasons come from my desires and not from, say, my neighbor’s desires? What is it that makes it so that the wise and sensible action to perform is whichever one accords with my aims?

Here’s the thing: I agree. Why should the fact that someone wishes to perform an action give them a reason to do it? I don’t think antirealists will be able to offer a satisfactory answer to this question. So what is the alternative? The way Bentham construes the dispute between realists and antirealists, each side thinks something like this:

Realists: We have reasons, and they are not given to us by our desires.

Antirealists: We have reasons, and they are given to us by our desires.

6.0 Crude Antirealist Desire Reductivism

But there is an alternative position an antirealist can take:

We don’t have normative reasons in any literal sense. To say that one has reasons to do things in ordinary language is a perfectly legitimate way to talk, but it does not imply or require any distinctive conception of “reasons” where they are understood as a distinct property or phenomenon given by desires or anything else. Instead, talk of reasons is best understood to be an idiosyncratic quirk of the English language; such talk can always be reduced to or redescribed in terms that don’t invoke the notion of “reasons.”

Talk of reasons, in most instances in ordinary language, can be understood in terms of claims about explanations, motivations, desires, hypothetical goals or values, or other mundane means by which such talk can be discharged without implying or entailing that one can literally have reasons. This view contrasts with analytic moral realism and antirealism in that both mistakenly reify reasons, treating them as things-in-themselves. Once this view is rejected, and we reject the notion that we have reasons in any literal sense, both the realist and antirealist accounts reveal themselves to rely on mistaken shared presuppositions.

This might sound absurd. But it is not absurd. It is, in fact, the least absurd position one can take on the matter. The reason the dispute between analytic realists and analytic antirealists appears intractable is because it is: both are committed to a mistaken view of “reasons” that reifies them, treating them as something that facts (for realists) or desires (for antirealists) can give or generate and that we subsequently literally have. One alternative is to reject the notion that there are reasons and that one can have them in some literal, irreducible sense, whereby reasons are something distinct from and given by something, whether it be facts or desires. One might construe such views as reductive, deflationary, or quietistic. Here’s a simple version of such a view:

Crude Antirealist Desire Reductivism

There are facts about what agents desire. There are also facts about what agents could desire or what others desire that they desire. To say that one has a normative reason isn’t to say that these desires or hypothetical desires give reasons, but rather that any verbal reference to one “having” a normative reason just is a reference to a real or hypothetical desire.

Let’s take this view and see how it handles Bentham’s characterization of a standard analytic antirealist account where desires “give” reasons:

The anti-realist presumption is generally that one’s reasons to behave in some way are given by their desires. (emphasis mine)

Note how Bentham’s remarks would make little sense if talk of reasons could be eliminated and replaced directly with talk of one’s goals, motivations, or desires. This is because the way Bentham frames things here, the desires give the reasons; they’re not identical to them.

Crude antirealist desire reductivism doesn’t have this problem. Reasons are not given by desires. Literally speaking, there are no “reasons.” References to reasons simply refer to desires, whether they are real or hypothetical.

Bentham continues:

Yet I do not see why the mere fact that one wishes to perform some act gives them a reason to do it. Why do my reasons come from my desires and not from, say, my neighbor’s desires?

On crude antirealist desire reductivism, these questions are no longer applicable. Reasons don’t “come from” desires. They just are desires. In other words, there are facts about what our desires are, and to say that one “has a reason” to do something just is to say that they desire to do it, or to imagine or project some hypothetical desire on them. For instance, to say:

Mike has a reason to avoid punching me in the face.

Could convey that:

It would satisfy Mike’s desires (even if Mike doesn’t realize it) to avoid punching me in the face.

I desire that Mike avoid punching me in the face.

There are intersubjective moral standards that, on reflection, Mike would endorse, according to which Mike would recognize that it’s against his interests to punch me in the face and would thereby no longer have the desire to do so.

There might be yet more desires/values one might be referencing with the initial remark about Mike “having a reason.” The point here is that all such talk terminates in the desires of some real (Mike, you) or hypothetical person (an idealized version of Mike) would have. On such a view, it’s not that your desire to perform an action gives you a reason to perform the action. It’s just that you desire to perform the action (or someone else desires that you do so, or a hypothetical version of you would desire to do so, etc.), and there are no further facts (such as that this “gives” you a reason to do so).

The second question about why your reasons “come from” your desires rather than your neighbors doesn’t really make sense, but an approximate response would be that the reason why your desires are your desires rather than your neighbors has to do with facts about the way human psychology works. Desires are generated by our brains. My desires come from my body, and my neighbor’s desires come from their body (I say “body” and not “brain” because desires are causally influenced by e.g., hormone release and other factors that are not directly located in the brain). For instance, when I desire to eat, this is not because my neighbor is hungry, but because of causal-historical facts about when I last ate, physiological facts about my metabolism, and neurophysiological facts related to e.g., hormone release and psychological elements of satiation. These facts provide a clear and (I hope, but who knows with philosophers) uncontroversial explanation of why I am hungry, and it is this hunger that causes my desire to eat.

The only reasonable sense in which my desires even are my desires rather than my neighbor’s desires already presupposes the legitimacy of a distinction like this (and if one wants to get into some Parfitian skepticism about identity, that’d be quite a digression but it’d threaten more than just the antirealist’s views). Bentham continues:

What is it that makes it so that the wise and sensible action to perform is whichever one accords with my aims?

This is ambiguous. If by “wise” or “sensible action to perform” is understood in accord with instrumental conceptions of rationality, then the answer is straightforward: to be wise or sensible in the relevant sense just is to act in such a way so as to effectively achieve one’s desires. If this isn’t what Bentham means, then he may be invoking some realist conception of being wise or sensible. If so, it wouldn’t make sense to ask how an antirealist could meet such demands, since they’re an antirealist! It’d be like asking an atheist, “What makes it the case that your atheistic view is wise and sensible according to God?” Bentham has a problem with remarks like this. He sometimes employs ambiguous remarks that, when disambiguated, reveal themselves to be trivial or unmotivated. This is one such instance.

Once we reject any lurking realist conceptions of being wise or sensible, it is clear that antirealists are not obligated to think that one’s desires are wise or sensible in any deeper sense than that they are wise or sensible relative to one’s own desires, where “desire” is broadly construed to capture one’s overarching set of values. In other words, if you’re an antirealist, you’re not going to have any trouble being an antirealist about what’s wise and sensible.

Bentham goes on to give examples that purportedly show how radically counterintuitive it would be for antirealist to maintain that we have reasons (or don’t have reasons) to do certain things. For instance, it’s supposed to be absurd to claim that if a person desires to eat a car, then they “have a reason” to eat a car. Criticisms of this sort fail to distinguish between a particular philosophical account of what a particular sentence means, and what that sentence would mean on some other account. Take a phrase like:

“There is magic in the world.”

This phrase could be used to convey that the kind of magic in Harry Potter is real. But it could also be used to convey the less fantastical claim that there are incredible and mysterious things in the world that inspire wonder. Interpreted in the first way, the statement would be false. In the second, it may be true. Just so, the desire-reductive antirealist is not obliged to accept the conceptual and/or metaphysical confusions of realists like Bentham when using or responding to snippets of ordinary moral discourse. Take, for instance, someone who says:

“Oh, for Pete’s sake.”

Must this person be committed to the notion that people literally have sakes? No. This would be ridiculous. Likewise, the mere fact that the desire-reductive antirealist would say things like:

“I have good reason to avoid intense suffering.”

…does not commit them to thinking they literally have reasons, where reasons are understood be something distinct from and in addition to one’s desires, values, preferences, goals, and so on. Such a statement could just be another way to say:

“I desire to avoid intense suffering”

Or:

“Conditional on the goal of avoiding intense suffering, it would be in one’s interests to avoid it.”

…or any number of locutions that don’t presume that one’s desires give one reasons; talk of “having reasons” on such an account is just a roundabout way of saying something about one’s real or hypothetical desires, values, goals, etc.

I want to pause here for a moment to say a bit about how I think about language, and to illustrate why I think Bentham and others are employing bad methods that reliably lead them to make egregious mistakes. These mistakes are, I believe, a product of induction into analytic philosophical methods that retain profound and pervasive misunderstandings about language and meaning from a warped, anti-psychological and anti-empirical 20th century conception of language. These mistakes lead Bentham and others to be systematically insensitive to pragmatics. Formally speaking, pragmatics is often construed as the study of how context contributes to meaning. I find this to be a bizarre definition, since I don’t think context contributes to meaning so much as constitutes, or fully determines it. One way to put this is that, personally, I reject the pragmatics/semantics distinction; for me, there is only pragmatics. It is context all the way down. This may be a radical or mistaken position, but adopting it or agreeing with me isn’t at all necessary to sustain the kinds of objections I raise here. One need merely appreciate that pragmatics plays a significant enough role to account for the kinds of errors I outline here.

This insensitivity to pragmatics is coupled with an obsessive, narrow focus on contemporary English, to the almost total exclusion of any consideration of how things are phrased in other languages. Like all languages, English is replete with verbal roundabouts and nonliteral or oblique ways of phrasing things. “Having” a reason is just one of many examples.

Languages evolve through the decentralized accretion of accepted linguistic mutations in a patterned but ultimately unplanned way. This is true of most languages most of the time throughout most of history, anyway, with the exception being constructed language or deliberate efforts to introduce order into a language, though this is the exception and not the norm. At the same time, language is never used outside a context (since this would be impossible). For comparison, one cannot use a knife, but not use it in any particular way. To use something is to use it in some way, to some end, for some purpose, and so on. Language is no different. Every word, every sound, and every gesture intentionally used by someone is used to some end or purpose. Meaning is to be located in those ends and purposes, not in the words, sounds, or gestures themselves. Language is a means to an end. The end is located in facts about the psychology of the language users, not the words and gestures themselves. In sloganized form: words don’t mean things, people mean things.

Utterances, writing, and phrases are always used in some context, meaning that they are used for some purpose or goal. Real language is always contextualized, embodied, and concrete. Language is a behavior, and behaviors are the goal-directed activities of agents. Agents differ in their goals, even when employing the same set of words in the same language. Language is improvisational and flexible, adapting on a momentary basis to the communicative goals of people interacting with one another. Once one appreciates this, they can start to appreciate the sharp disparity between the kinds examples Bentham works with and the real thing. Bentham routinely asks us to assess sentences, but these sentences are presented without any context. They aren’t being uttered by anyone in particular in any actual context to any conceivable end, apart from what few details are stipulated. But even these stipulated details are still fictional. If I say “Imagine Alex yelled at his neighbor because he was angry,” you are not considering any actual instance of any actual person actually yelling at anyone. Yet Bentham will routinely present us with sentences and situations that lack the contextual cues we’d ordinarily use to make judgments. Does a desire to eat cars sound weird? Well, what if the being in question was a giant mechanical monstrosity that consumed metal? Now would it be weird? If we’re to imagine a person who wanted to eat cars, despite the fact that they’d be unable to metabolize parts of the car or even succeed at biting off parts of it, it’d be entirely appropriate to presume that they had some pathology. But that’s just it; the context is missing, and so we’re given open-ended, vague scenarios where conscious and unconscious processes alike are left to fill in the gap.

7.0 The “That’s absurd!” objection

The most obvious rejoinder to an account like this is that it’s absurd to claim that we don’t have reasons. But it’s important to be clear about what this means. What this means is that, literally speaking, we don’t have reasons, with emphasis on have. It’s not that one can’t speak of reasons, or speak of us “having reasons,” provided one doesn’t mistakenly reify the notion of having reasons such that one believes that reasons are a literal thing one can have. On such a view, talk of “having reasons” is perfectly sensible. Critics of a view like this may be inclined to make the following sort of move:

This position is ridiculous. It would commit the antirealist to saying things like “We have no reason to do anything” or “we have no reason to avoid torture and dismemberment.” But we clearly do have reasons to do at least some things, and this includes the fact that we have a reason to avoid torture and dismemberment.

This is false. The desire-reductive antirealist is not committed to saying these things. Whether the antirealist is committed to agreeing that we have no such reasons will depend on the context in which such a remark is presented. If the desire-reductive antirealist is in a conversation with philosophers who make it clear that they are speaking of reified reasons “given” by facts, desires, or whatever else, the desire-reductive antirealist doesn’t think there are reasons of this kind. But the desire-reductive antirealist isn’t therefore obligated to import the metaphysical or conceptual presuppositions of mainstream analytic philosophers into ordinary language, and suppose that they and others are somehow committed to speaking and thinking in ways that comport with the analytic philosopher’s penchant for reification. It is entirely consistent with the position to construe ordinary use of reason-talk in a way consistent with the antirealist’s view, and thereby speak of “having reasons” in ordinary contexts. Note how insane it would sound, in ordinary contexts, to say something like:

I’d like to buy a sandwich from your sandwich shop, and you’d like to sell it. So we both share a common desire to make a transaction. However, we have no reason to do so.

Or:

I know I’m in a burning building and I very much want to live, but I have no reason to avoid sitting in this chair and burning to death.

These remarks sound insane because they are insane. But why do they sound insane? These remarks sound insane because of the way pragmatic implication works. To say that I would like something or wants something in these remarks, but then to immediately say that one “has no reason” to do so sounds like an inappropriate attempt at Gricean cancellation. Here’s a simple example of where cancellation would work. John sits down to dinner with some friend, and there are many dishes at the table to choose from. John sees a pizza and says:

Wow! That pizza looks delicious!

This could be taken to imply that John would like a slice of pizza. However, John could cancel this implication by adding:

Wow! That pizza looks delicious! Unfortunately, I’m watching my carbs, so I’ll have to pass.

Note how the qualification “Unfortunately…” cancels the implication of the initial remark, and does so in a fairly natural way. This works because the initial remark may imply a desire to eat the pizza, but doesn’t logically entail such a desire. Now compare this to the latter of the preceding examples:

I know I’m in a burning building and I very much want to live, but I have no reason to avoid sitting in this chair and burning to death.

In this context, a natural interpretation of “having a reason” would be something like having a desire or motivation. So the remark sounds nonsensical and internally contradictory. Imagine if we “translated” both parts of the sentence into explicit desire language:

I desire to live and not be burned to death, but I have no desire to avoid dying by being burned to death.

This is now a clear contradiction and an obvious nonsense phrase. What realists who criticize antirealists often do is take remarks like this (though they often leave out a second clause with a “but…” or something similar), that contrast a statement about the implications of some action or event that one would ordinary expect people to have specific desires or motivations in relation (e.g., desire to avoid pain or a desire to avoid torturing people, respectively), then contrast this with some weird or repugnant desire. This is how future Tuesday cases work:

I know I will be in intense agony on Tuesday, but I have no desire to avoid such pain.

This sounds insane because we expect normal people to want to avoid intense agony regardless of what day it is. The cancellation here is technically legitimate: it is not a logical entailment of the fact that one will be in intense agony on Tuesday that therefore one must have a desire to avoid it (though this might be contestable on some views), but it sounds weird. Why does it sound weird? Because our standard profile of people is that they very much want to avoid intense agony. What I believe is happening with realists is that they project, or impose, schemas or models of conventional motivational profiles onto the entities in hypothetical scenarios, and this creates a kind of “ghost contradiction” or “ghost conflict” between the explicit, stated desires of the agent in the hypothetical, and the realist’s strongly felt sense of what an agent is expected to, or “ought to” desire. This conflict generates a sense of unease or “wrongness” in the realist, which they then mistakenly interpret as a signal that there’s something mistaken or impossible about the situation.

This yields your standard “intuition” that the person in this scenario “ought to” want to avoid such agony, even when it is explicitly stated that they simply don’t care about whether they are in agony on Tuesday (it might also be that realists don’t want other people to be in agony even if those people want to; there might be a number of psychological explanations that account for the realist’s stance on these matters without granting them some special truth-tracking power).

Now, to get back to the original point, imagine how it would sound if antirealists went around saying things like:

I have no reason to refrain from setting you and your family on fire.

Or:

Nobody has ever had a reason to drink a glass of water.

These remarks sound insane. Why do they sound insane? The first would, in ordinary contexts, pragmatically imply that the person making such a remark may wish to harm you. This makes them sound dangerous and insane. More generally, the claim that one has or doesn’t have a reason, in ordinary language, often carries pragmatic implications about one’s goals, desires, or motivations. Critically, this would be true even if moral realism was true, and even if we had stance-independent reasons. Suppose, for instance, a moral realist sees a person drop their wallet. Their friend suggests they keep the money in it, and they say:

That would be wrong!

Does this remark merely convey that they consider it morally wrong to keep someone else’s wallet? No. It also implies that they desire or are motivated to not keep the money, and, presumably, that they are about to go chase the person who dropped the wallet down to return it to them. This is how actual moral judgments work in real ordinary contexts, unlike the decontextualized, abstract moral sentences Bentham and other moral philosophers typically deal with. Actual moral judgment occurs in a real-world context, where, whatever one’s philosophical commitments, one’s judgments typically carry implications or convey pragmatic implications about one’s goals, desires, motives, intentions, and so on, at the very least in addition to whatever one’s philosophical commitments might be.

In light of this example, let’s now return to the objection that the person who claims that we don’t literally have reasons is somehow committed to saying things like:

I have no reason to refrain from setting you and your family on fire.

Nobody has ever had a reason to drink a glass of water.

That they are somehow committed to saying these things without qualification, regardless of the conversational context, is absolutely false. While it is true that, in a philosophical context in which it is explicitly specified that “reasons” are reified in the sense Bentham thinks they are that they are committed to affirming these statements. But what this commits them to is only this:

I have no stance-independent, reified reason to refrain from setting you and your family on fire.

Nobody has ever had a stance-independent, reified reason to drink a glass of water.

Now is it obvious that these statements are ridiculous or nonsensical? It might “seem obvious” to Bentham or other moral realists, but I hope they would be less confident that ordinary people without training in philosophy would quickly and consistently share the same judgment that these statements are ridiculous. I hope, instead, they’d appreciate that many people would react by saying:

“…What the hell is a stance-independent, reified reason?”

All the desire-reductive antirealist is committed to is affirming these statements in a highly rarefied academic context in which rival conceptions of “reasons” are explicitly specified. They are not thereby committed to saying the same things outside of these contexts in ordinary language. Why? Because in those contexts, such remarks at least carry pragmatic implications about goals, desires, or motives, even if reasons-talk wasn’t fully reducible to them. So in an ordinary context, these statements would be best interpreted as:

I have no reason to refrain from setting you and your family on fire. I am seriously considering doing so because I’m a psychopath that enjoys threatening other people with a painful death.

It has never been in anyone’s interest to drink water.

The subtext of the first remark doesn’t assert something that is necessarily false (though it probably is, since most antirealists are not psychopathic arsonists), but it nevertheless would be understood in ordinary contexts to imply that the speaker is dangerous and evil. Why would an antirealist be committed to saying such a thing? They wouldn’t. But moral realists like to claim that they would, and in doing so can prompt people who lack adequate training to recognize this rhetorical trick for what it is (in fact, I think that moral realists themselves usually fail to recognize the misleading rhetorical nature of this move. This is a lose-lose for realists. If they do realize this is what they’re doing, and do it anyway, they are malicious. If they don’t, this raises questions about their competence).

The second remark would assert something idiotic and clearly false. Once again, realists exploit the conflation between a purely “semantic” reading of a sentence outside ordinary contexts of usage, where the only features of the sentence are carried by the theoretical commitments of the theory under discussion, and the ordinary language reading, which includes the pragmatic implications of the sentence, including the subtexts outlined above (that the speaker is evil or stupid). Moral realists, like analytic philosophers more generally, consistently conflate semantics and pragmatics, fail to notice the pragmatic features associated with the ordinary language uses of phrases, and then react in an entirely appropriate way, via their sensitivity to such pragmatics, by rejecting the statements in question, but then mistakenly misattribute these appropriate rejections of the statements not to the pragmatic implications of the statements but to some “intuition” that supports rejecting rival theories, which are almost always also semantics-only theories that have nothing to do with pragmatics in the first place.

In short, my diagnosis of the mistake analytic philosophers make is that, by studying analytic philosophy, they have adopted a mode of evaluating sentences that systematically impairs their ability to interpret language accurately, which results in the systematic misattribution of the causes of their judgments, and in turn causes them the theorize about competing philosophical theories on the basis of such misattributions. In short, philosophers systematically induce themselves into a state of localized incompetence, then theorize while in this state of self-induced incompetence. The result is a broad, systematic propensity for error that implicates just about every area of analytic philosophy. Since Bentham drinks up mainstream analytic philosophical presuppositions like a firehose, he has mastered this mode of misguided theorizing.

8.0 Applying the diagnosis

With the desire-reductivism account and this diagnosis in hand, let’s see what Bentham says next, and assess how well it applies. Following Bentham’s questions about why our own desires should give us reasons rather than our neighbors, and why we should think it is wise or sensible to act on our desires, he says:

This becomes clearer when one considers more vividly cases where a person has a desire to perform an act but no reason to perform it otherwise. Suppose that a person has a strong desire to throw their mug across the room or smash their hand against the table. Do they really have any reason to do so? Or suppose a person has a strong desire to consume a drug, even though doing so would give them no pleasure. Do they have any reason to consume it? I believe the answer is no.

On my account, these questions make no sense. It would be a bit like asking:

If a person has a strong desire to throw their mug across the room or smash their hand against the table, do they really have a desire to do so?

Yes.

If a person has a strong desire to consume a drug, even though doing so would give them no pleasure. Do they have any desire to consume it?

Yes.

That was easy. Note the leveraging of weird preferences and apparent “inconsistencies” in the above examples.

Throwing a mug across a room

Smashing your hand against a table

Taking drugs even though they won’t give you pleasure

The first example is a weird desire most people wouldn’t have. The second desire is a weird desire because most people don’t want to cause themselves pain. And the third desire is a weird desire insofar as we presume that one’s primary or sole motivation for taking a drug is to feel pleasure.

Note that in all these cases, the “intuition” we’re supposed to have that one “doesn’t have a reason” to do these things relies on underspecification. By not specifying a context that might account for why a person might want to perform these activities, Bentham can exploit a reader’s presumption that one would perform these activities “for no reason,” or on a whim or impulse, or because they have inexplicable alien desires utterly unlike human desires. But of course, we can readily imagine reasons why a person might want to do any of these things:

Throwing a mug across a room to hit an intruder as a method to slow them down.

Smashing your hand against a table because it is encased in ice and you want to break off the ice.

Take drugs even though they won’t give you pleasure because you have an illness and they’d treat the illness.

It is trivially easy to come up with “reasons” why someone would want to do any of these things that would immediately be acceptable to just about anyone, including Bentham, by simply coming up with some context where the action promotes a typical desire we’d expect someone to have (to stop intruders, maintain use of one’s appendages, recover from illness, etc.). The moment we start describing people acting on arbitrary, seemingly-purposeless whims is the moment we begin important notions of mental illness or profound weirdness. Far from serving as appropriate testing grounds for assessing the limitations of antirealist accounts, such implications can instead distort and warp our assessment of the scenarios if we are insensitive to pragmatics or insensitive to the psychological processes causing our judgments or reactions to these scenarios. Such insensitivity, coupled with misidentification, is what I think is actually going on with Bentham and others.

I hypothesize that Bentham and others have adopted an approach to philosophy that prompts them to systematically misidentify twinges of emotion, discomfort, or judgments of infelicity as a special faculty for truth detection. Instead, what is happening is that these psychological processes are prompting “code red” or “something weird is going on here” reactions when philosophers try to jam the square peg of bizarre scenarios through the round hole of ordinary language, the latter of which presupposes a kind of background normality. That poor fit prompts a reaction, which is mistakenly taken to be an indication that any theory one can concoct that would prompt such a reaction is therefore mistaken. I would like to see Bentham offer a convincing rebuttal to the preceding points, but I want to move on to address the form of antirealism Bentham addresses in the article.

9.0 A return to analytic antirealism

I’ve presented a crude reasons-reductive antirealist account as a position that circumvents all of Bentham’s concerns. I doubt this will satisfy Bentham, but I don’t know what Bentham would say about the position because he doesn’t address it. Instead, Bentham addresses what I can only imagine is a kind of mainstream analytic antirealist position:

Now, my sense is anti-realists often think it is an analytic truth that your reasons are given your desires. It is, they claim, true by definition. But this is hard to believe. Suppose my friend does not want to get life-saving surgery that would benefit him in the long-run. Or suppose my friend has an unfortunate predilection for recreational homicide. I say to him “come on, you have reason to stop murdering,” or “you have a reason to get the surgery.”

I think Bentham should rely on more than just his sense. He could try asking antirealists. At least a few have responded and offered alternative accounts. I predict Bentham will not substantively engage with any of these positions. Make of that what you will.

At any rate, I’m an antirealist, and I don’t think it’s an analytic truth that your reasons are given by your desires. That sounds like complete nonsense to me. Bentham continues:

I think what I am saying is true. But even if you deny that it’s true, it seems, at the very least, that my position is substantive. I am not simply speaking nonsense or misusing language. Yet if it was an analytic truth that you have reason to do what you most want to do, then my sentence would be equivalent to saying “you want to stop murdering,” which would be trivially false. So long as the value realist position isn’t a misuse of language, it must not be an analytic truth that reasons are given by desires. So long as you can coherently ask whether one has genuine reason to do what they want, it can’t be an analytic truth that one has reason to do what they want.

Bentham just isn’t saying much of substance here, so let’s deal with this quickly:

I don’t care if Bentham thinks what he’s saying is true. This is trivial to point out

He uses “it seems” without qualification. It seems that way to who? It does not seem that way to me. I don’t think Bentham’s position is substantive. I don’t know if I’d say it “seems” like it isn’t substantive, but it certainly doesn’t seem to me that it is.

I think Bentham probably is speaking nonsense or misusing language. But who cares what I think? I explain at least part of the reason why I think this here.

I’ll separate off these last two remarks to address them specifically:

So long as the value realist position isn’t a misuse of language, it must not be an analytic truth that reasons are given by desires.

While this is true, it is also true that even if we reject that it is an analytic truth that reasons are given by desires, it does not follow that the value realist position isn’t a misuse of language (which, again, I think it is).

So long as you can coherently ask whether one has genuine reason to do what they want, it can’t be an analytic truth that one has reason to do what they want.

This is also true. So now one might expect Bentham to provide a compelling explanation of what he means by a “genuine reason” and to explain how one can coherently ask whether we have them. He does not do this. Instead, we’re treated to repetition, assertions, and rhetorical questions:

Anti-realists generally claim that we have a reason to pursue our ends, but no reason to have the ends in the first place. Our reasons, it is claimed, are just given by our ends. But this seems to make real reasons illusory! How can you have a reason to take an action in furtherance of an end if you have no reason to have that end?

Once again, Bentham simply appeals to how things “seem,” presumably to Bentham himself. Why should any of the rest of us care how things seem to him?

Bentham continues the use of deceptive and misleading language by using the phrase “real” reasons. He should know better by this point.

Bentham picks up on the last question in the next paragraph, adding:

I only have a reason to buy a plane ticket to Paris if I have a reason to go to Paris. And yet if going to Paris is simply something I choose, how does that give me a reason? The fact that I decided to aim at something doesn’t seem to make aiming at it the wise or prudent thing to do. And what explains why we have any reason to pursue our aims? As we’ve seen, it isn’t an analytic truth. So why is it true?

Bentham appears to be smuggling in realist presuppositions here. He says “The fact that I decided to aim at something doesn’t seem to make aiming at it the wise or prudent thing to do.” What does he mean by “wise” and “prudent”? If we adopt antirealist conceptions of wisdom and prudence, it would be trivially easy for one’s decision in this case to be wise and prudent. If we adopt a realist conception, well, of course one’s desire-given reasons wouldn’t be stance-independently wise and stance-independently prudent. Bentham once again poses an ambiguous question that, when disambiguated, either asks something trivial that an antirealist could easily address, or asks something impossible and inappropriate: for the antirealist position to be able to account for realist presuppositions.

And what explains why we have any reason to pursue our aims? As we’ve seen, it isn’t an analytic truth. So why is it true?

Why is it true that a bachelor is an unmarried man? Why is any analytic truth true? Whatever your answer: plug it in here. Bentham continues with this muddled line of thought, straddling the ambiguity of various nonmoral normative terms as he continues to struggle with trying to force antirealist positions to accommodate his realist positions, which they obviously can’t do:

The division between what you have a reason to do and what you want to do becomes clearer in cases where you want to do things that are unreasonable. Suppose you want to eat a car, for example. Or set yourself on fire, not because you’d enjoy being set on fire, but just because of a brute desire. Or perhaps you want to stay up late, even though you know it will make tomorrow much worse. It seems clear that you have a reason to behave otherwise—that you will be behaving irrationally if you behave that way.

Once again, what does Bentham mean by unreasonable? If by “reasonable” we’re invoking a notion of instrumental rationality whereby an act is reasonable insofar as it furthers your ends, then it’s trivial for an antirealist to point out how acting on your desires furthers your ends: your ends are your desires. Even I, the arch-nemesis of people claiming things are obvious, must acknowledge that acting on your desires furthers your desires! If, on the other hand, Bentham means stance-independently unreasonable, then Bentham would just be begging the question by supposing there are cases where what you have reason to do and what you want to do come apart. Once again, once you disambiguate Bentham’s language, his objections are either trivial or false (and in this case, question begging). Bentham caps off these remarks with yet another appeal to his personal intuitions:

It seems clear that you have a reason to behave otherwise […]

If by “it seems clear” Bentham means he personally an intuition that you “have a reason to behave otherwise” then what we have here is the autobiographical report of a realist about reasons, i.e., someone who thinks there are stance-independent reasons, and, critically, in this case they think this because they have the intuition that they have stance-independent reasons, criticizing an antirealist account on the grounds that it is inconsistent with his personal non-antirealist intuitions. Of course it is. It would have to be. Bentham continues with more scenarios presumably intended to serve as intuition pumps that elicit realist intuitions in his readers. It’s largely a waste of time. If they have them, they may reject antirealism. If they don’t, they won’t. What we need is a way to move past this initial stage setting to actually determine which side is correct. And this will not be achieved by self-reporting our personal intuitions (if we even have those). Note how emphatic Bentham gets, though:

Or, to take a more peculiar example, imagine that you are indifferent to pain in your colon. You cannot differentiate between your colon and pancreas. But you simply, at a higher-level, don’t care at all about pain from your colon. Currently, you are writhing around and screaming in agony. You instruct the doctor: check to see whether the pain originates from my colon or pancreas. If it is from my pancreas, then of course you should treat it. But if it’s from my colon, then keep it as it is.

This just seems so clearly irrational!

Once again, by “clearly irrational” does Bentham mean stance-dependently (or “instrumentally”) or stance-independently. If instrumentally, then he’s wrong; it would be rational. If he means stance-independently, then it doesn’t “seem clearly [stance-independently] irrational” to me, and I don’t particularly care if it seems that way to Bentham. Bentham also continues using the misleading modifiers. Remarks like “genuine desire” and “there wasn’t really any reason” spring up in the paragraphs that follow. Then we get to Bentham’s “final gripe”:

I have a final gripe with the claim that it is an analytic truth that one has reason to pursue their ends, which is that this fails to make it the genuinely wise, rational, or sensible thing to do.

This isn’t a final gripe. Bentham already alluded to this concern earlier and it suffers the same problem as his other gripes. First, he once again uses the misleading modifier “genuinely.” In case it bears repeating, antirealists are not obligated to agree that something would only be wise, rational, or sensible, if it were stance-independently wise, rational, or sensible. On the contrary, if the antirealist believes they have the correct conception of normative concepts like “wise,” “rational,” or “sensible,” then things are only wise, rational, or sensible in the antirealist’s sense, and not in the realist’s sense; as such, it would in fact be the antirealist who believes things are wise, rational, or sensible in the respect that they actually are, which is a pretty good candidate characteristic for referring to them as “genuine.” What Bentham is doing throughout this article is helping himself to a rhetorically loaded term that surreptitiously frames the realist’s normative conceptions in a more positive and desirable light than the antirealist’s. Bentham should be aware of this, and, again, to my knowledge, has not offered any substantive rebuttal to this point. Maybe Bentham isn’t aware of this, and is oblivious to the point. Or he is, but doesn’t agree there’s anything inappropriate about using such language. If the latter, I’d like to know what the rationale is for continuing the use of such language.

As I said, this remark suffers the same problem as every preceding remark: once one disambiguates the meaning of “wise,” “rational,” and “sensible.” If these are understood in an antirealist way, then the antirealist can trivially meet the conditions for all three. If these are understood in a realist way, then they can’t. Bentham continues:

Suppose someone claims that it is true by definition that the morally right action is to maximize pleasure minus pain. I am skeptical of this semantic account. But even if it was correct, it would seem to give no genuine reason to maximize pleasure.

If this is correct, it would tell us only that people use the word moral to refer to maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. But why does that give us any genuine reasons? How people speak tells us nothing about the sensible way to behave. “Oh no, if I don’t act as a utilitarian, my actions will no longer merit certain folk-theoretic names!”

This sounds like analytic naturalism, which is a form of moral realism, not antirealism. And the link at the end of this remark is to an article largely focused on criticizing metanormative concerns about agency, and didn’t appear to me at a quick glance to raise the same kinds of concerns as the antirealist views he’s criticizing here. But maybe I’m missing something, or he just wanted to reference that cool David Lewis quote at the beginning of the essay.

The questions that follow from Bentham are quite strange to me:

In similar fashion, suppose it is an analytic truth that you have most reason to do whatever it is you desire. All that would mean is that English speakers typically use the word reason to refer to people getting what they desire. But how does that make that the sensible or wise way to behave? If I’m deciding how to behave, why should I care about whether I can aptly be described as rational, if the word rational is just a veiled term for a person who does what they aim at.

Personally, I think of “desires” broadly as those factors that motivate me to act. I’m not sure how I could engage in any voluntary actions that I didn’t desire to engage in. I don’t think I’d be comfortable calling that an analytic truth, but how, after deliberating, would one consider and be motivated by something other than a desire if they didn’t desire, or want to in some sense, act in accord with such non-desire considerations (in other words, how can one act on non-desires if one doesn’t at least have a second-order desire to do so)? This isn’t a rhetorical question; not all philosophers are Humean or at least Humeanesque, and so they will have some alternative view. But I personally wonder whether such views won’t be, from a psychological perspective, word salad or pseudoscience that fails to accord with how human cognition actually works. Bentham anticipates this kind of response:

It might be claimed that one has no choice but to do what they want. Every time you perform an action, you desired to perform that action. Yet this account seems at risk of saying that people never act irrationally, for they always act in ways they want.

This oversimplifies things. Those of us who think we are motivated by desires don’t just think that people have desires and then whenever they act, they acted consistently with a desire and were therefore rational. This is why I objected to use of the term “desire” way back at the start of this essay. “Desire” is a term Bentham and other philosophers toss around sloppily and with little regard for the fact that, whatever a desire is, it is a feature of human psychology, and the crude, unscientific terminology philosophers routinely employ may not adequately capture the details, and complexity, of how human cognition operates. “Desire” is a folk psychological term that fails to capture the different physiological and neurophysiological processes associated with motivating agents to act. Psychologists don’t typically even construe “desires” as a single, distinct phenomenon, but rather draw distinctions between dissociable phenomena, or, in some cases, even propose collapsing folk distinctions altogether (for instance, see this account that collapses belief and desire into prediction). Just as philosophers draw distinctions, psychologists draw distinctions, often not on the basis of a priori considerations but on what data reveals about the form and function of human behavior and the cognitive (and other physical processes) involved in behavior.