Pragmatism & Prediction

Some time ago, Mike Huemer wrote an article discussing “absurd” theories of truth. I don’t want to address the article as a whole, but instead want to focus on two components: the linguistic tests Huemer favors, and pragmatic accounts of truth.

Huemer suggests that, under certain conditions, namely, when a proponent of a view doesn’t think terms like “true” express a given concept in English, they should subject these accounts to “tests of linguistic usage”:

[...] rival theorists of truth should submit their disagreement to tests of linguistic usage. We should try to think of examples where the rival theories of “truth” would make different predictions about what ordinary speakers would say.

This is fine so far as it goes, but one issue with Huemer’s approach is that he doesn’t seem to rely on gathering empirical data on what users do in fact say. Rather, Huemer seems content to presume to know what they’d say if asked. But perhaps Huemer would be open to empirical data were it gathered, and simply regards armchair judgments as reasonable interim data until empirical findings are available. Either way, Huemer presents pragmatic accounts of truth as a candidate for such tests:

For example, the Pragmatic theory predicts that ordinary speakers should find the phrase “useful falsehood” nonsensical. They should disagree with T-schema sentences (e.g., “‘Snow is white’ is true if and only if snow is white.”) They should judge that “Is it useful to believe what’s true?” means the same as “Is it useful to believe what’s useful to believe?” They should be happy with changing the standard courtroom oath from “I solemnly swear to tell the truth…” to “I solemnly swear to say what is useful…”

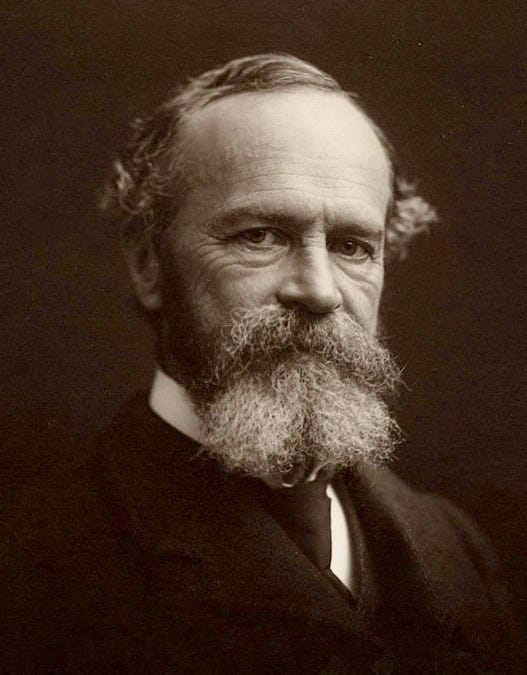

This isn’t true, and it leads me to wonder how familiar Huemer is with the various forms of pragmatism. If we’re going with, e.g., classical pragmatism, William James already addressed claims like this in The Meaning of Truth. I also grant that Huemer has presented a conditional here: that if one is making claims about what is expressed by the ordinary concept, then such tests are in order. But a pragmatist need not take themselves to be making such claims. However, the central issue is that classical pragmatism wouldn’t predict that people would consider the notion of a useful falsehood nonsensical because classical pragmatism itself doesn’t regard the notion of a useful falsehood as nonsensical.

On a classical pragmatist account, truth requires more than a belief simply being locally expedient to a prospective believer. It’s not the case, then, that any belief can qualify as true provided it is (proximally) useful, e.g., it does not hold that if it was useful to believe I was the smartest person alive because it would boost my self-esteem, then it is true that I am in fact the smartest person alive. Usefulness is a bit more complicated than this, not the least because the usefulness of a belief consists, in part, in how well it synergizes with the rest of one’s belief, and how well it stands the test of time, e.g., believing you’re not seriously ill and in need of treatment might feel fine now, but if you don’t get treatment, you’re still going to die.

Pragmatism takes a holistic approach to truth, where truth is the result of our overall ongoing acts of inquiry, taken as a whole. True beliefs, on this view, are the scarred and battered survivors that work together, that cohere with one another, and that have withstood the slings and arrows of their role in our entire worldview tested against the world via our experiences. The truth of our beliefs thus does not consist in any arbitrary value they can provide on an à la carte basis, but in their role in making predictions and allowing us to anticipate future experiences alongside the rest of our beliefs. Thus, while there is a perspectival element to truth, and truths will turn out to be useful, this does not guarantee that anything useful will be true.

James is at pains to clarify, repeatedly and out of clear frustration, that pragmatism does not mean, “If useful, then true.” Lots of beliefs could be and are useful but false on the pragmatic view, since there are a wealth of ways in which a view could be useful to this or that end but not qualify as true given pragmatism’s broader and more robust requirements for truth than mere expedience. At the very least, a belief only earns its status as true if it fits well into the rest of our beliefs, like a piece fitting well into a broader jigsaw puzzle of other beliefs.

One way to put this is that even if usefulness is a necessary condition for truth, it is not a sufficient condition; a belief must at the very least synergize with the rest of our beliefs as well, and the kind of usefulness it should exhibit involves more than any arbitrary role it could play in fulfilling some goal; goals can conflict with one another, and were a person to anoint as true any belief that had any use, without regard for its relation to the rest of one’s beliefs and their use, one would become hopelessly mired in contradictions. Pragmatists don’t propose we go that route.

It’s also worth noting that pragmatism may not be an appropriate target for these sorts of linguistic tests. Pragmatism was already emerging prior to and leading into the early 20th century, so it may also be anachronistic to frame the view in terms of what it would predict about ordinary language. However, even if we did want to associate predictions with classical pragmatism:

(1) It’s not clear that James or others would predict that ordinary speakers should regard the notion of a “useful falsehood” as nonsensical, since (classical) pragmatism itself doesn’t hold that “useful falsehood” is nonsensical.

(2) It’s not clear, even if classical pragmatists did predict that ordinary moral thought, behavior, and judgment best fit a pragmatic approach, that this would lead to specific predictions about what people would say when asked, for reasons related to the methodological challenges associated with operationalizing claims about ordinary linguistic practice; i.e., even if people were implicit pragmatists and employed a pragmatic notion of truth, this wouldn’t necessarily entail any specific predictions about what they’d say about truth.

(3) More generally, even when a philosophical account includes empirical claims about ordinary thought or practice, it rarely entails any specific predictions about the outcomes of specific studies, since the relationship between a philosophical account (even one with empirical implications) and the methods by which we empirically test that account require the addition of auxiliary hypotheses about the measurement, validity, and interpretation of any particular attempt at operationalizing an empirical claim for the purposes of empirical evaluation. These auxiliary hypotheses aren’t entailments or part of the philosophical account itself, but are instead part of a broader network of theoretical commitments regarding proper research design in psychology, linguistics, etc. As such, it is generally a mistake to claim that a philosophical account predicts people would say such-and-such if asked.

(4) It’s not clear James or others would predict that the surface level judgments people have about what they take themselves to mean when they speak of truth would best fit the pragmatic account, even setting aside the notion of useful falsehoods. In fact James alludes to the possibility that the popular conception of truth isn’t aligned with the pragmatic conception of truth. In Chapter Six of Pragmatism James says:

The popular notion is that a true idea must copy its reality. Like other popular views, this one follows the analogy of the most usual experience.

Given this, it’s doubtful James would take ordinary people to respond to prompts about the nature of truth in a way consistent with pragmatism even if he took pragmatism to be an accurate account of how people employ the notion of truth. If he did make a such a prediction, it would just be an error on his part; such predictions aren’t an intrinsic feature of pragmatism, anyway.

James was no slouch when it comes to psychology (for reasons that, I hope, are obvious), but it took nearly a century for experimental philosophy to step onto the scene to actually test how nonphilosophers think about philosophical questions. Anyone familiar with such research will readily recognize that it isn’t so easy to predict what people actually think, whatever one’s philosophical perspective even if we can do a pretty good job of predicting what they’d say much of the time (though I doubt we’re very good at this, either). This is because responses to study probes may or may not be reflective of a person’s implicit philosophical views, since people can be confused, mistaken, or rely on faulty metalinguistic judgments. I address this at length here in section 8.0. I’ll quote the punchline of the points I make there:

One of the most important points to stress is that, even if you can predict the results of a study, that does not necessarily tell you how the respondents to that study think. Such a claim relies on the presumption that you’ve interpreted the results of the study correctly, such that the observed response patterns in your data are the result of valid measures and that you’ve interpreted them correctly. Correctly predicting, for instance, that most people would choose a “realist response” over an “antirealist response” does not entail that most of the respondents are realists, since this would only follow if choosing what was operationalized as a realist response actually indicates that the respondent is a realist.

I am, perhaps, a bit more familiar than most with the disconnect between what a philosophical theory suggests about ordinary thought and practice and what people would say if asked. Early on in my academic studies, I was interested in the question of whether nonphilosophers were moral realists or moral antirealists. I quickly came to suspect that the answer was “both”: that there was both variation between people, with some more committed to realism and others more committed to antirealism, and within each person’s judgments: a person may be a realist about some issues and an antirealist about others (I was heavily inspired by this paper from Gill, 2009).

Early research seemed to support this conclusion. For instance, Wright, Grandjean and McWhite’s (2013) findings supported what they called “metaethical pluralism,” which is exactly what it sounds like. However, I became disillusioned with the methods used in these studies as I became increasingly skeptical about whether participants were interpreting questions about moral realism/antirealism in a way consistent with researcher intent. This led to a preliminary paper on the topic (see Bush & Moss, 2020) and eventually culminated in my dissertation research, where I attempt to demonstrate that participants consistently interpret metaethical stimuli in unintended ways.

Why do I say all of this? Because even if a theory predicts people think or act in a way most consistent with a particular philosophical account, it does not thereby predict that if presented with statements philosophers recognize as consistent with that theory that the person in question will affirm those statements. There is a winding maze of methodological pitfalls between what philosophers intend to ask and how nonphilosophers interpret what they are being asked that can pose serious challenges to making any straightforward predictions about what people should agree or disagree with. In short: it’s just not true that pragmatism predicts that people should find the phrase “useful falsehood” nonsensical. It’s not true, first and foremost, because this phrase isn’t even nonsensical on the pragmatist account, but second, even if it were, it still wouldn’t entail such a prediction.

Philosophical accounts about what’s true, as well as accounts about ordinary thought and practice, don’t entail straightforward predictions about how people would respond to stimuli. This is because how people respond to stimuli involves a host of methodological and psychological facts concerning, e.g., the role of demand characteristics and other social factors that influence how participants respond to prompts under laboratory conditions, facts about the relation between use and metalinguistic intuitions (see Martí, 2009), facts about the validity of the measures being used and the success of whatever operationalization is employed, facts about the conceptual consistency between one’s empirical operationalizations and the philosophical account they’re intended to correspond to, facts about whatever idiosyncrasies may obtain in a given language that could influence interpretation, facts about interpersonal variation in the psychology of participants that could not only lead to mismatches between researcher intent and participant interpretation, but also interpretative variation between participants (some of which may be systematic across populations and subpopulations, leading to problems related to measurement invariance), and…well, I could keep adding to this list, but I think I’ve illustrated the point well enough: there are many, many hurdles that one must cross before one moves from armchair philosophy to philosophically informed psychology.

To put it bluntly (and, I hope, not too harshly), philosophers who make crude pronouncements about what a philosophical position predicts about how ordinary people would respond in an experimental context who aren’t sensitive to, and take proper account of, the preceding considerations are not well informed and any criticisms predicated on those predictions are tainted by that naivety.

If you want to make claims about what a philosophical theory predicts about how people would respond, you are doing psychology. Philosophers are fond of criticizing scientists who insist they don’t need philosophy and that they aren’t personally making any philosophical assumptions. Philosophers are quick to note (and rightly so!) that such people rely on philosophical presuppositions whether they realize it or not, observing that one can either do philosophy consciously and do it well, or one can do it unwittingly and do it poorly.

This is no less true of philosophers: if one wants to dabble in psychology, but not take proper stock of what’s needed to do it well, then they’re not in a position to claim they’re not doing psychology. They are doing psychology. Just badly.

Huemer’s objections to pragmatism fail on three fronts. At least some forms of pragmatism don’t regard the notion of useful falsehoods as nonsensical, so it would make no sense to predict that ordinary people (if they were pragmatists) should do so. Second, pragmatism is not necessarily in the business of making such predictions in the first place. Third, even if pragmatism were intended to offer a description of ordinary thought and practice, and even if it did hold that useful falsehoods were nonsensical, it wouldn’t necessarily predict that nonphilosophers would explicitly agree when prompted. As some small evidence to the contrary, James appears to describe correspondence as the “popular” view. Huemer has offered us little reason to think pragmatism is an absurd account of truth.

References

Bush, L. S., & Moss, D. (2020). Misunderstanding metaethics: Difficulties measuring folk objectivism and relativism. Diametros 17(64): 6–21.

Gill, M. B. (2009). Indeterminacy and variability in meta-ethics. Philosophical studies, 145(2), 215–234.

Martí, G. (2009). Against semantic multi-culturalism. Analysis, 69(1), 42–48.

Wright, J. C., Grandjean, P. T., & McWhite, C. B. (2013). The meta-ethical grounding of our moral beliefs: Evidence for meta-ethical pluralism. Philosophical Psychology, 26(3), 336–361.

Thanks, this was very helpful. What I found most interesting is exploring the sense in which a useful falsehood makes sense under pragmatism. I probably have as inaccurate a picture of pragmatism as Huemer, so it's good to be set straight(er) on this stuff.

Useful fiction is a common concept, an LLC for example.