The Folk Philosophy Fallacy (Part 2)

Twitter Tuesday #21

Knobe & Prinz and the folk conception of phenomenal experience: Study 1

This post is part of a series. For previous entries in the series see:

2.2 Knobe & Prinz (2008)

Next, we have Knobe and Prinz (2008), hereafter “K&P”. This section is going to be a bit longer than is typical for these kinds of sections. I wanted to spend the time to actually dig into a study a bit, to show unfamiliar readers what they look like and how they work. A kind of window into the world of experimental philosophy, if you will. If that’s not of interest to you, feel free to skip this section and move on to section 3.

K&P present evidence that nonphilosophers distinguish between phenomenal and non-phenomenal states. Let’s take a look at how they do this. Knobe and Prinz begin with two hypotheses, but only the first is relevant to the question of whether nonphilosophers have a concept of phenomenal consciousness, so we will focus on that:

Nonphilosophers “have a concept of phenomenal consciousness” and use this concept when drawing distinctions between different mental states (p. 68).

K&P propose that people are receptive to indications of phenomenal consciousness (PC) when ascribing mental states to others. Some states require PC, while others do not. For instance, when we see that a person is in pain, we implicitly attribute PC to that person, while we may not do so when attributing other mental states (e.g., goals) to people or other agents (e.g., computers). Attributions of PC are not confined to pain alone, but encompass other mental states that draw on the concept of PC. They give a handful of examples:

Involve PC attribution:

Sasha is vividly imagining a purple square. (p. 69)

Sasha is experiencing intense joy.

Do not involve PC attribution:

Sasha is wondering what to do

Sasha is considering his options

To those familiar with the concept of phenomenal consciousness, there is nothing mysterious about the above distinction. The former two statements appear to refer to qualitative aspects of one’s experiences, whereas the latter are more “informational”: they involve deliberating or weighing up the pros and cons of different courses of action, something one might imagine a “nonconscious” machine can do, even if a machine does not have a first person point of view.

This study arose in the early days of experimental philosophy, but even then researchers were careful to address one common misunderstanding when people hear about studies like these: they are not claiming that nonphilosophers have an explicit theory or concept of phenomenal consciousness that they subscribe to:

To a first glance, this first hypothesis may seem a bit absurd. After all, it is clear that most people would not understand the words ‘phenomenal consciousness,’ and when one tries to explain the concept in a classroom, students often have trouble understanding what it amounts to. It would certainly be foolish, then, for us to suggest that people ordinarily have explicit beliefs about whether particular mental state types do or do not require phenomenal consciousness. But that is not at all what we have in mind. What we mean to suggest is rather that people grasp this concept at a purely tacit level. In other words, the suggestion is that people are actually applying the concept all the time; it’s just that they normally have no awareness of doing so. (p. 68)

Their second hypothesis is not as relevant to our concern here, but I’ll go over it anyway, since it sets the stage for the study that they conducted.

K&P draw a distinction between the function of a state and the physical state of a given entity or object. Functional states center on the role things play, that is, what they do and what they’re for, while physical states refer to the substance and structure of the thing in question. For instance, if we were to talk about the function of memory, we might say that it is to store information for future use, while if we were to talk about the physical state of memory, we’d describe those features of a brain (or perhaps a computer) physically involved in the maintenance of a given memory. They emphasize that this distinction is important because two entities with different physical structures could, in principle, exhibit similar functions. We could encounter beings from another world, or advanced artificial intelligences, that are capable of thought or emotion, even if their physiology or structure were radically different from our own.

If we were to encounter such beings, how might we judge whether they were angry or sad or intended to buy a coffee? Presumably, we’d observe what they do, i.e., their functions, rather than pop open their brains or motherboards and start snooping around to see if they’re structured in the same way as our brains.

K&P propose that attributions of PC are sensitive to distinctive criteria that other mental state attributions are not sensitive to, and the functional/physical distinction plays a role in attributions of PC. In particular, they propose that “the process underlying ascriptions of states that require phenomenal consciousness makes use of information about physical constitution in a way that other mental ascriptions do not” (p. 71).

They propose to test this by presenting participants with agents that prompt participants to draw distinctions in mental state attributions consistent with their hypothesis. They opt for group agents. Why? They provide an extended rationale that leads up to this choice (pp. 71-73), including research showing that when people were asked to judge whether the statement “Some corporations want lower taxes,” on a scale from 1=Figurative to 7=Literal, the average score was 6.2, indicating a strong inclination towards judging such a statement to be meant literally (Arico, Fiala, & Nichols, 2011, p. 334, footnote 8).

I have reservations about this from the very outset. It appears to be a reference to a pilot study mentioned in a footnote, which raises questions about how robust this result is. But setting that aside, I wonder what participants were thinking when they judged that “Some corporations want to lower taxes” was literally true rather than figuratively true. They give an example of a comparison item that was judged on average to be figurative: that “Einstein was an egghead,” though they don’t report the mean score for how literal participants judged items like this. Participants may have a higher threshold for judging something to be figurative rather than literal. People may, for instance, judge that a statement is literal when its intended meaning is clear and uncontroversial, and not necessarily because they are implying some implicit concept of mental state attribution (or some other implicit philosophical theory).

That corporations “act” “as if” they want to lower taxes is hardly controversial, and that this is the case is not something people are likely to consider a matter of “opinion” in the sense of being an irresolvable issue of personal judgment or subjective taste. Whereas whether or not Einstein “was an egghead” carries negative normative connotations that have a subjective vibe to them. Maybe that could drive a difference in judgment.

Or perhaps “egghead” is so obviously a kind of nonsense statement that it easily passes the bar for being figurative, while speaking of corporations as if they had thoughts and goals, even if figurative, is so natural that it flies under the inattentive participants’ radar, and they would, were the fact that they appeared to be implying a corporation literally has goals and motivations, would, on reflection, deny this. I don’t know, and maybe the literature addresses this somewhere, but either way, this finding, itself, struck me as fairly superficial.

The theoretical motivations behind the paper are a bit of a digression, but I want to draw attention to a general methodological concern with studies: often studies rely on past research, and if past findings are not on firm foundations, one may be building their own research program on a house of cards. The ongoing replication crisis in psychology strongly hints (I would go so far as to say that it confirms) that experimental psychology not only relies on poor methods but has relied on such methods for a very long time. The discipline has never truly established itself as the rigorous enterprise it should have been, in part because it’s never laid down firm foundations in one or more central guiding theories, as physics and biology have. Until psychologists grapple with the need for firmer theoretical foundations, we’ll continue to see wobbly towers of literature crash down from time to time.

K&P leverage this notion of group agents because it provides a familiar, everyday example that participants are more likely to relate to than the far-fetched thought experiments philosophers often indulge in. You know, the sort that feature robots and space pirates and sentient doorknobs. People often balk at these scenarios, and there may be good reason not to use them: they may be cognitively demanding, or distract people, or prompt a humorous response that undermines efforts to dispassionately prompt the appropriate cognitive states.

Second reason for employing group agents is that people already seem to attribute mental states to group agents despite the fact that group agents are physically very different from individuals. While people talk about what nations or corporations “intend” to do, or what they “think” about a given issue, they don’t have brains or nervous systems:

From the standpoint of physical constitution, group agents are radically different from individual human beings. In individual humans, decision-making is realized by neurons, synapses and firing rates. In a group agent, decision-making might be realized by committees, memos and emails. Clearly, the decision making of group agents can be realized by physical objects that have no parallel in individual humans. (p. 71)

Fair enough! So, what do K&P do with this?

2.2.1 K&P Study 1

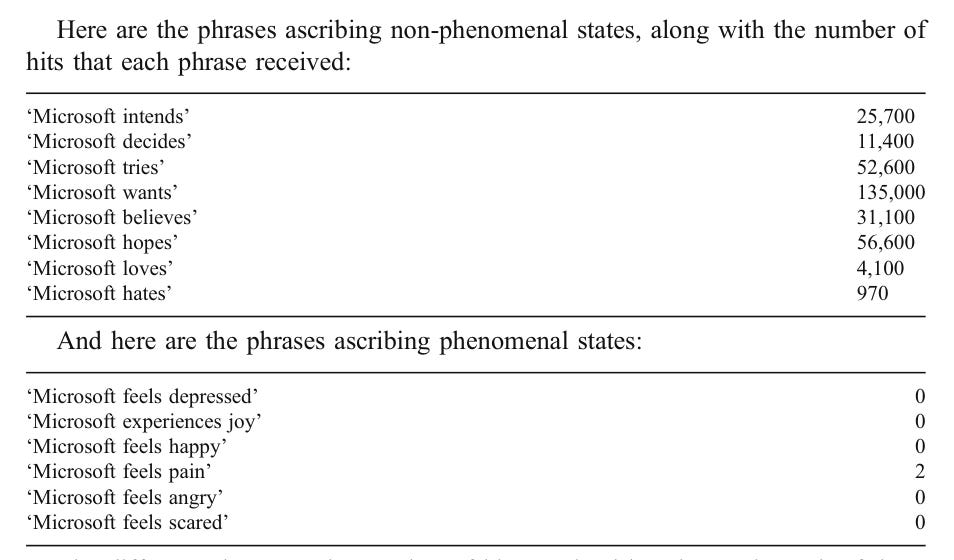

First, K&P wanted to demonstrate that people appear to attribute mental states to group agents, but do not attribute mental states associated with PC. They did this by entering phrases indicative of non-phenomenal and phenomenal states into Google and seeing how many hits they got. Here’s what they found:

Figure 1: Knobe & Prinz (2008). Google search results for non-phenomenal and phenomenal states.

The article was published in 2008, so these results were obtained sometime that year or earlier. I did a quick check and things haven’t changed much since then:

Non-phenomenal

"Microsoft intends" 47,000

“Microsoft decides” 193,000

“Microsoft tries” 38,400

“Microsoft wants” 503,000

“Microsoft believes” 62,000

“Microsoft hopes” 216,000

“Microsoft loves” 92,600

“Microsoft hates” 92,200

Phenomenal

“Microsoft feels depressed” 4

“Microsoft experiences joy” 4

“Microsoft feels happy” 7

“Microsoft feels pain” 2

“Microsoft feels angry” 5

“Microsoft feels scared” 3

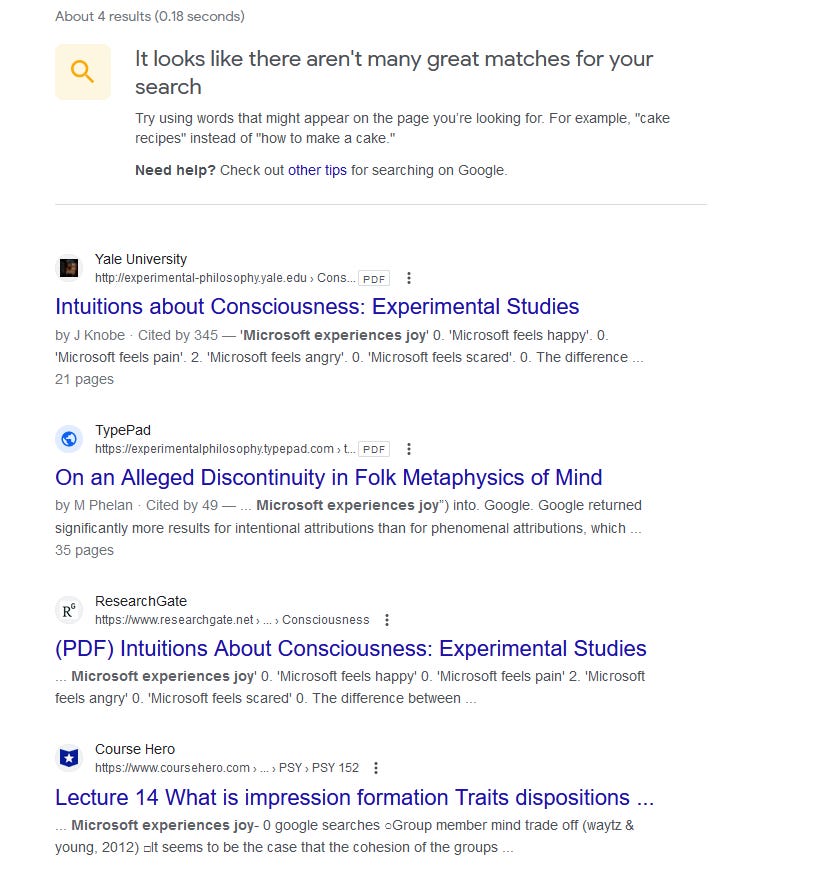

One of the amusing aspects of redoing this research is that almost all of the increased hits for the phenomenal states is a result of the publication of this study. Have a look:

The same pattern occurs for all of their other examples. I find this really amusing. While the addition of 4 search results does nothing to undermine their hypothesis, imagine their article had gone viral, become famous, and been cited many times. If it did, there might be a few hundred or even thousand hits for it by now. It would be a rare case in which the very act of publishing a study making a particular point would serve to appear to undermine that point (even if, of course, it doesn’t actually do so).

While I think this approach provides some information about the relative use of the phenomenal vs. non-phenomenal language, I have some concerns about this approach.

First, K&P employ what seems to be an a priori classification for nonphenomenal and phenomenal terms. We’re to simply grant that terms like “intends” and “decides” are non-phenomenal, but that “feels” and “experiences” aren’t. I’m not sure that we should grant this. It’s an open empirical question how, exactly, people think about these terms. I doubt people rigidly employ the former set to only refer to non-phenomenal states, and the latter to refer to phenomenal states, even if people did distinguish the two. Language is highly context-sensitive and vary in the way they’re used. It’s more likely that whether someone were drawing a verbal distinction between phenomenal and non-phenomenal states that this would be mediated more holistically, by how they were using terms in the broader context of the terms around them, the situation the person was in. Even so, if the data is consistent with their a priori classification, this would be more consistent with their hypothesis than at least many alternatives, anyway, so it would still be relevant and support their hypothesis. This concern, then, is not meant to completely undermine the way they’ve sat things up, but instead to plant a flag of potential concern.

Granted, this doesn’t mean the use of certain terms wouldn’t correlate with the non-PC/PC distinction, but it’s an open question how strong that correlation is, and it would at least introduce quite a bit of noise into whatever measures one might use. You might point to the fact that the numbers for non-phenomenal states are so much larger that this is unlikely to be a serious problem. And that may be true. However, you have to be careful when conducting a study: a study itself presents a particular context, and if that context prompts thinking or using language in ways that happen to coincide with nonstandard usage of terms, then you could skew results in ways that don’t reflect usage of those terms outside the study.

Another issue to observe with this study is that the non-phenomenal states consist of two words: Microsoft intends, decides, tries and so on, while the phenomenal states include a third term. Doing so adds greater specificity, which can greatly restrict the number of hits you get for these items. I’m not sure what the rationale behind this choice is, but if we add a third term to some of the non-phenomenal phrases (this is difficult, because most are grammatically disposed to require 4 or more terms to say something specific, because you’d need to add something like ‘to’), we get much fewer hits, while if we drop the third term from the phenomenal state phrases, we get many more hits. Let’s give this a try:

Non-phenomenal

“Microsoft loves customers” 3

“Microsoft loves customers” 1

Phenomenal

“Microsoft feels” 12,200

“Microsoft experiences” 25,700

See the problem? These hit results may simply be an artifact of using two-term searches for non-phenomenal phrases and three-term phrases for phenomenal phrases. Note one significant issue: “Microsoft Experiences” is a thing, so that’s likely inflating the hits on the latter. That is, if there’s a distinct proper noun that happens to be taking up a lot of the hits, then it’s not clear how many people are actually saying “Microsoft experiences…” in a sentence. Of course, both “feels” and “experiences” receive fewer hits than any of the non-phenomenal phrases, anyway, so overall K&P would probably be correct in suggesting people seem to use the terms they classify as non-phenomenal with reference to Microsoft more often than terms they classify as phenomenal.

They do acknowledge the following:

But now we face a problem. We know that people use certain English expressions more frequently than others, but we do not know precisely why they do this. It could be that the whole effect is due to some trivial difference like the number of words contained in each expression or the frequency with which people generally ascribe different types of states. (p. 74)

There are yet more problems with the particular way they approached this problem. As Kerr (2013) points out:

The way one couches one’s search terms is critical here. If one searches for ‘Microsoft was happy’ rather than ‘Microsoft feels happy’ one gets around 76,200 hits (at time and place of writing), presumably because the former is a much more natural way to convey a similar meaning. Even so, one cannot do this with all of Knobe and Prinz’s examples and it does seem that we are more comfortable attributing some mental states to groups and not others. ‘Microsoft envisions’ was not part of their study although my own search returns around 12,300 results so it seems ‘envisions’ might be closer to the non-phenomenal group than the phenomenal. (p. 6)

I agree with the general sentiment here. It does seem that people are more willing to attribute “non-phenomenal” mental states to Microsoft than “phenomenal” states, if we take the terms K&P use at face value and actually suppose they are or could be picking out such a distinction. Even so, at the very least, the specific contrast, of tens of thousands vs. virtually no hits, is likely an exaggeration of the degree of difference in attribution, and that may be due to differences in how people would be disposed to employ the terms in question, which may be more naturally conveyed in different grammatical forms than the ones K&P opted for.

Next week, I will wrap up the Knobe and Prinz studies by covering studies 2, 3, and 4.

References

Kerr, E. (2013). Are You Thinking What We’re Thinking? Group Knowledge Attributions and Collective Visions. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective, 3(1), 5-13.

Knobe, J., & Prinz, J. (2008). Intuitions about consciousness: Experimental studies. Phenomenology and the cognitive sciences, 7, 67-83.

[Non Philosopher Here]

I might be missing conceptual distinctions here, but the P/NP seems to be pretty much equivalent to "feelz"/other internal processes. Is there more to this, I wonder.